POS Trends to Watch in 2017

1. A focus on Health Equity in POS Tobacco Control

While the smoking rate has declined to 15.1% for US adults nationally, higher rates of smoking persist among populations that are lower income, have a lower level of education, are LGBTQ, have a serious mental illness, as well as among American Indian/Alaska Natives, males, younger adults, and those living the Midwest or South.

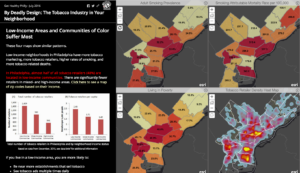

The tobacco industry has historically targeted marginalized groups with tobacco advertising campaigns and promotions. Marginalized groups continue to be exposed to disproportionately high levels of tobacco marketing and sales. Today, greater tobacco retailer density, which is tied to higher rates of smoking, can be found in areas with greater proportions of low income families and people of color. What started as the “Menthol Wars” continues today with greater menthol marketing in areas with higher numbers of low-income and black residents.[1] Menthol products are also often cheaper in areas with a higher proportion of African American residents, [2] areas once deemed “focus communities” for menthol products.[3]

We now know more about what works to help eliminate some of the disparities in retailer density. Recent research conducted in New York and Missouri has shown that bans on stores near schools could nearly eliminate disparities in density between neighborhoods.[4] A ban on stores near schools can be accomplished through licensing, and we know that licensing strategies with caps on the number of retailers within a geographic area can work to reduce disparities in density, as has been done in San Francisco and Philadelphia.

We also know that increasing price is the gold standard for reducing tobacco consumption, but increasing price may also help eliminate disparities in tobacco use. Racial and ethnic groups that smoke at the highest rates also currently pay the least for their cigarettes.[5] In addition to raising excise taxes, non-tax price policies can help to raise the price of tobacco and prevent the tobacco industry from circumventing the effects of tax increases.[6] Lower income smokers are more likely to purchase discount brands, so policies like minimum floor prices that raise the price of discount brands and prohibit the use of promotions that would drop the price below that minimum level could help reduce socioeconomic disparities in smoking.[7] Licensing and pricing policies can also work together in combination to increase the impact on disparities.

Health equity can be considered as a part of any tobacco control policy. For instance, concerns have been raised about potential equity issues in enforcement of some Tobacco 21 laws that penalize the purchase, use, or possession (PUP) of tobacco rather than the sale of tobacco products. While PUP laws have been criticized for being ineffective in reducing youth tobacco use, they also could have the unintended consequence of potential inequitable enforcement against young persons of color. See Tobacco 21 Tips & Tools from TCLC for more. Localities can consider conducting a health equity impact assessment to determine what the results of any given policy may be on the ground. An approach considering social determinants of health can help practitioners ensure the benefits reach all population groups and that resources and services are distributed consistently and equally across populations so as not to exacerbate existing disparities.[8]

In addition, we expect to see tobacco control become part of a broader conversation about health equity in 2017.

2. Tobacco Retailer Licensing as a mechanism to implement policy solutions that are most relevant and potentially impactful for local communities

Tobacco retailer licensing (TRL) is a regulatory tool that can be used to implement a range of policies. In the simplest form, a TRL policy requires stores that want to sell tobacco to register with the city, county, and/or state. Often, they are also required to pay an annual fee to apply for or renew a license to sell tobacco products. Licensing allows for more accurate tracking of all tobacco retailers in a given locality, which can help with policy enforcement and compliance checks. It can also serve as a platform on which to build other regulations that can have a large impact on the community environment, restricting the density, type, and location of tobacco retail outlets. An increasing number of localities and states are advocating for and implementing TRL policies to address youth access, disparities in retailer density, and to begin regulating e-cigarette sales and vape shops.

San Francisco currently has the most comprehensive tobacco retailer licensing policy – capping the number of licenses permitted in each of the city’s 11 districts at 45 and prohibiting any new retailer from locating within 500 feet of a school or other retailer. However, more cities are moving towards a similar model. In December 2016, Philadelphia passed a law limiting the number of tobacco retailers to 1 per 1000 people in each planning district and prohibiting new tobacco retailers within 500 feet of a school. Over 81 cities and towns in Massachusetts have instituted some sort of cap on the total number of tobacco retail outlets, and 60 of them also have restrictions on how close tobacco retailers can be located to schools. Several cities in California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Wisconsin also limit retailers within 500 or 1000 feet of schools.

Mapping can help communities determine the impact of any given TRL policy on the ground – e.g. how many tobacco retailers are currently located near schools in their town or where disparities in tobacco retailer density rates exist in their community. It can also help determine what TRL “plug-ins” might have the most impact on the tobacco retail environment in their community.

3. Flavored Tobacco Restrictions – Including Menthol

New York City and Providence, RI were the first two cities to restrict the sale of all flavored non-cigarette tobacco products, except for menthol, but a growing number of cities and counties across the country are considering flavored tobacco product restrictions, and an increasing number are moving towards including menthol restrictions.

In July 2015, the Minneapolis City Council passed new restrictions on the sale of flavored tobacco products, which restrict the sale of flavored tobacco products, other than menthol flavored, to adult-only tobacco stores. They can no longer be sold in convenience stores, where youth frequent. The impact of the ordinance includes a reduction in the number of retail outlets for flavored tobacco products in the city from 420 to 25 stores. Shortly after Minneapolis passed their regulation, St. Paul followed suit, and later in 2016, the town of Shorewood, MN passed a similar law. While the Minneapolis law exempted menthol, the Association for Nonsmokers -Minnesota and partners are now educating the public on menthol and have produced a video about how tobacco companies target youth, African-Americans, LGBTQ individuals, and other marginalized populations – called “Beautiful Lie, Ugly Truth.”

In December 2013, Chicago became the first city in the U.S. to restrict the sale of all flavored tobacco products, including menthol, banning sales within 500 feet of K-12 schools. While the ordinance was recently partially rolled back to allow the sale of menthol near elementary schools, the ordinance still represents a significant milestone. Berkeley, CA followed suit in 2015 and banned the sale of flavored tobacco products including menthol and e-cigarettes within 600 feet of schools.

At least 43 municipalities in Massachusetts had some sort of flavor ban in place as of April 2016. Of note – Marion, MA is considering a policy that would completely prohibit the sale of all menthol products in addition to flavored products. If the ordinance passes and stands up to legal challenges from the tobacco industry – which other flavor restrictions have done – it could pave the way for others to follow the town’s lead.

Expect to see more media and awareness campaigns around flavors and menthol as well. With CDC funding, the Pasadena Department of Public Health launched a campaign in late 2016 as part of their REACH (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health) project that focuses on menthol cigarettes, flavored tobacco products, and e-cigarettes. Ads will appear on buses, at bus shelters, on social media, and at the point of sale inside participating tobacco retailers. One of the goals of the campaign is to advance health equity by battling the tobacco industry’s targeted marketing and higher rates of use among African Americans and Hispanic/Latinos in the city. View the ads and learn more here.

Expect to see more media and awareness campaigns around flavors and menthol as well. With CDC funding, the Pasadena Department of Public Health launched a campaign in late 2016 as part of their REACH (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health) project that focuses on menthol cigarettes, flavored tobacco products, and e-cigarettes. Ads will appear on buses, at bus shelters, on social media, and at the point of sale inside participating tobacco retailers. One of the goals of the campaign is to advance health equity by battling the tobacco industry’s targeted marketing and higher rates of use among African Americans and Hispanic/Latinos in the city. View the ads and learn more here.

Learn more about flavored tobacco products here.

4. Tobacco Free Pharmacies

In 2014, CVS, the nation’s second largest pharmacy chain, ended tobacco sales. In 2008, San Francisco was the first city to enact a tobacco free pharmacy policy, and Boston followed later that year. Since then, 7 other cities and counties in California, 144 towns in Massachusetts, and one county in Minnesota have passed local tobacco-free pharmacy laws. However, 53,566 pharmacies across the country still sell tobacco. In 2017, momentum may be picking up to change that.

In December 2016, the Truth Initiative partnered with DoSomething.org and Kira Kosarin of Nickelodeon’s “The Thundermans” on a new campaign called “Take Back the Shelves,” which encouraged youth to create art depicting what they would rather see on pharmacy shelves in place of tobacco and post it on social media. The campaign generated 3857 posts and 67,498 participants. Now, the Truth Initiative, Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights, and Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids are all calling on Walgreens to end tobacco sales.

Walgreens shareholders requested a vote on whether to discontinue tobacco sales in their stores to take place at their meeting in January 2017. While Walgreens executives have blocked the vote, don’t expect the issue to go away.

Some smaller pharmacy chains across the country have opted to stop selling tobacco voluntarily. For example, in 2015, the California grocery company Raley’s decided to stop selling tobacco, and in 2016, announced they would begin to stock the check-out aisle with “better-for-you” products. Shop-Rite in New Jersey ended their tobacco sales in 2014. In Vermont, 98% of independent pharmacies no longer sell tobacco (watch this video to learn more about why, in their own words).

Localities can create tobacco-free pharmacies through part of a tobacco retailer licensing program by restricting the type of stores that may be issued a license to exclude pharmacies, or through a law that directly prohibits tobacco sales in pharmacies.

Learn more about tobacco-free pharmacies.

5. Product Watch: “Reduced Risk” Products

Under the FDA’s recent deeming rules, no tobacco product may be marketed with modified risk health descriptors (e.g. “light,” “low tar,” “mild”) unless specifically approved by the FDA.

In December 2016, the FDA denied Swedish Match’s request to remove a required warning from its snus packages stating that the product can cause gum and tooth loss. However, the FDA deferred action on the company’s two other requests: 1) to remove a warning that the product causes mouth cancer and 2) to revise a third warning statement to say that the product “presents substantially lower risks to health than cigarettes.”

Phillip Morris International has now submitted their heat-not-burn product “iQOS” for approval to market as a modified risk product. Company executive have also been quoted saying they see a future where they no longer sell cigarettes, only these “reduced risk” and alternative products instead.

Debate continues as to if and how e-cigarettes can be an effective harm reduction product, whether they can serve as an effective cessation tool, and how to keep youth from initiating nicotine and tobacco use with them.

We’ll be keeping an eye on these trends, while also staying focused on combustible tobacco products. While we don’t know the long-term effects of e-cigarettes, we do know that combustible tobacco products are the leading cause of death and disease in the US, contributing to 480,000 premature deaths each year, and with the tobacco industry spending over $8.2 billion yearly to market these deadly products at the point of sale, we’ve got plenty of work to do fighting the “War in the Store.”

Trends Continuing from 2016:

6. Tobacco 21

The Tobacco 21 movement has grown substantially within the last year, with California joining Hawaii as the second state to raise the minimum legal sale age to 21. Now over 200 cities and counties in 14 states have passed Tobacco 21 policies in their communities. Many localities are also including e-cigarettes in their ordinances, raising the minimum legal sale age for all tobacco products.

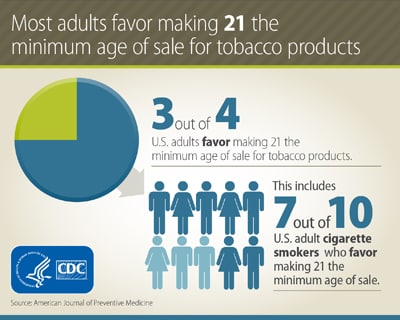

Given the high level of support for the policy, we expect the list of cities, counties, and states with Tobacco 21 laws to continue to grow in 2017. Nationally, 75% of adults support raising the age to 21, including 7 out of 10 smokers.[8] It has been a policy that has been able to gain traction in areas with little other point of sale policy activity. While this momentum is promising, localities considering Tobacco 21 may find it helpful to their overall tobacco control work to consider framing it as part of a broader comprehensive plan to limit youth access to tobacco and the effects of tobacco marketing and/or including it as part of a licensing program that allows for additional point of sale tobacco control interventions.

Given the high level of support for the policy, we expect the list of cities, counties, and states with Tobacco 21 laws to continue to grow in 2017. Nationally, 75% of adults support raising the age to 21, including 7 out of 10 smokers.[8] It has been a policy that has been able to gain traction in areas with little other point of sale policy activity. While this momentum is promising, localities considering Tobacco 21 may find it helpful to their overall tobacco control work to consider framing it as part of a broader comprehensive plan to limit youth access to tobacco and the effects of tobacco marketing and/or including it as part of a licensing program that allows for additional point of sale tobacco control interventions.

One challenge for implementation within the Tobacco 21 movement concerns enforcement. While the ability to enforce the policy at a local level through compliance checks is critical,[9] enforcement can be conducted in a number of different ways. One approach is to place the burden of responsibility on the tobacco retailer rather than on the underage purchaser. For example, in March 2012, the City of Chicago voted to raise the MLSA for tobacco to 21. However, the ordinance also removed the fine for possession of tobacco for those underage, holding the tobacco seller accountable rather than young people who have been targeted by the tobacco industry. The evidence of the effectiveness of PUP provisions in reducing youth tobacco use is limited, particularly among those at higher risk for smoking, and the laws may have adverse consequences for youth already addicted.[10] For more information, see Tobacco 21: Tips & Tools and Tobacco 21: Sample Ordinance from the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium.

Expect the conversation about Tobacco 21 to continue in 2017.

7. Partnerships to create healthier places: tobacco, food, alcohol, physical activity!

Intervention in the retail setting presents the opportunity to address multiple factors that influence health. The evidence behind how exposure to tobacco advertising and promotions at the point of sale contributes to tobacco use behaviors continues to grow. Across multiple studies, research has shown that youth more frequently exposed to tobacco promotion are 60% more likely to have tried smoking and 30% more likely to be susceptible to future smoking.[12] However, community interest in creating a healthy retail environment continues to grow – not only with regard to tobacco but also including alcohol, food, and marijuana, as well as how the community retail environment can support physical activity. The retail environment includes both the community environment (e.g. number, type, and location of stores) and the consumer environment (e.g. what products are sold, how they are advertised, prices, etc). A recent study of food retailers that also sold tobacco in 3 North Carolina counties found that the community and consumer environments for nutrition, physical activity, and tobacco were inter-related, indicating that measures assessing solely community level can miss characteristics of the consumer environment. [11]

Policies can address the retail environment holistically as well, tackling multiple issues at the point of sale in coordination instead of addressing each in isolation. The authors of the study in North Carolina suggest that food ordinances requiring licensed grocery stores to sell a minimum standard of healthy food, like Minneapolis’s staple food ordinance, can be expanded to place a cap on the amount of tobacco marketing allowed outside the store and reduce youth exposure. [11] Given that areas with a higher number of tobacco retail outlets are also more urban and more walkable, restricting exterior advertisements to reduce youth exposure may be more important. [11] Further improvements to the aesthetics of the store exterior, such as better lighting, removing graffiti, providing adequate trash receptacles, and preventing loitering could be incorporated as requirements for participation in healthy store programs in order to encourage walkability and active transport around the store. [11]

Monitoring of tobacco, e-cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, food and beverages can also be done with Counter Tools’ Store Audit Center. Find other food environment measurements in the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research’s Measures Registry.

For more strategies on interdisciplinary collaboration to create healthy retail environments, review:

- Case Study: Healthy Retail San Francisco

- Integrating Tobacco Control and Obesity Prevention Initiatives at Retail Outlets, published in the journal Preventing Chronic Disease.

- ChangeLab Solution’s Healthy Retail: A Set of Tools for Policy and Partnership, which includes a healthy retail Playbook, Conversation Starters, and a Collaboration Workbook.

- California Department of Public Health’sHealthy Stores for a Healthy Community