Healthy Retail

In this evidence summary, we examine how communities are working together to create healthy retail environments for all using similar tactics across tobacco, cannabis, alcohol, and food, as well as finding ways to address how these products are sold and marketed in stores simultaneously. It is not intended to be an exhaustive report, but to provide an overview of how similar tactics are being used across products at the point of sale and to highlight how thinking about the retail environment as a whole can benefit the health of our communities. Click on the strategy below to learn more about how it can be used to address a variety of products at the point of sale:

In this evidence summary, we examine how communities are working together to create healthy retail environments for all using similar tactics across tobacco, cannabis, alcohol, and food, as well as finding ways to address how these products are sold and marketed in stores simultaneously. It is not intended to be an exhaustive report, but to provide an overview of how similar tactics are being used across products at the point of sale and to highlight how thinking about the retail environment as a whole can benefit the health of our communities. Click on the strategy below to learn more about how it can be used to address a variety of products at the point of sale:

- Licensing, zoning & retailer density

- Pricing strategies

- Health warnings

- Advertising

- Product placement

- Voluntary healthy retail changes

Background

The World Health Organization identifies tobacco, alcohol, and other processed foods as leading contributors to non-communicable diseases. Cannabis, a product that is increasingly being legalized for adult use retail sale in states across the country, is also associated with a number of negative impacts to the brain and mental health. The availability of these products and how they are promoted, placed, and priced in stores affects health behaviors related to consumption. Interventions in the retail setting present the opportunity to address multiple factors that influence health.

Policies can address the retail environment holistically, tackling multiple issues at the point of sale in coordination instead of addressing each in isolation. The authors of one study in North Carolina suggest that food ordinances requiring licensed grocery stores meet stocking requirements for healthy food, like Minneapolis’s staple food ordinance, can be expanded to place a cap on the amount of tobacco marketing allowed outside the store to reduce youth exposure.[2] Given that areas with a higher number of tobacco retail outlets are also more urban and more walkable, restricting exterior advertisements to reduce youth exposure may be more important.[2] Further improvements to the aesthetics of the store exterior, such as better lighting, removing graffiti, providing adequate trash receptacles, and preventing loitering could be incorporated as requirements for participation in healthy store programs in order to encourage walkability and active transport around the store.[2]

Tobacco use behaviors also often intersect with issues related to food, cannabis, alcohol, and place-based social determinants of health. For example, smoking and food insecurity can be interdependently related both on an individual and neighborhood level. A cross-sectional health interview survey and food environment assessment in Schenectady, NY showed an association between higher odds of smoking and each of six different indicators of food distress: 1) consuming 1 or fewer serving of fruits and vegetables per day, 2) food insecurity, 3) receiving SNAP benefits, 4) using a food pantry, 5) living in a neighborhood with low access to healthy food, and 6) shopping for food at a store with limited healthy food choices.[3] Stores types with limited food options also had more tobacco product availability and advertising, compounding the potential ill effects on health.[3] People who smoke may spend more of their income (up to 24%) on cigarettes, which leaves them less money to spend on food.[3] Smoking also can also act as an appetite suppressant, and chronic food insecurity can increase stress, which may further dependence on nicotine.[3] Given this interdependence, creating retail environment that minimize the influence of tobacco may help support quit attempts in food insecure populations. Increased collaboration between tobacco and nutrition public health workers on healthy retail programs and policies may both reduce tobacco use and improve dietary behaviors.

Licensing, Zoning, and Retailer Density

Tobacco

A high density of tobacco retailers, often measured as the number per 1,000 people in a given geographic area, impacts tobacco use behaviors in a number of harmful ways, including higher rates of youth tobacco use initiation, increased consumption among current smokers, and making quit attempts more difficult. Learn more about tobacco retailer licensing, zoning, and density here.

Food

Just as a concentration of tobacco retailers can detract from community health, so can an absence of retailers selling healthy food or an overabundance of retailers selling unhealthy food.

The lack of access to fresh, healthy food is a complex issue not always solved by adding a grocery store. Factors of race, culture, income, education, structural inequalities, restrictive covenant policies, food quality, and nutritional knowledge also play large roles. For these reasons, some prefer the terms “food apartheid,” “healthy food priority areas,” or “low-access communities.” Learn more here and here.

The term “food swamp” has been used to describe areas with a high density of places selling unhealthy food (e.g. fast food restaurants, convenience stores selling junk food) and a lack of healthy food options.[5] This is similar to the term “tobacco swamp,” which is used to refer to an area with a high density of tobacco retailers. Too often, these terms describe the same neighborhoods: where there are more lower-income residents and people of color. A 2016 study found that the more low-income and Hispanic students In a school, the greater the likelihood that there are both fast-food restaurants and tobacco retailers located nearby.[6]

Just as licensing and zoning can be used to restrict the number, type, and location of tobacco retailers in a community, these types of policies can also be used to impact the number, type, and location of food retail retailers. For example, in April of 2018, the City Council of Tulsa, Oklahoma, passed the Healthy Neighborhoods Overlay policy, which requires all new small box discount stores (e.g. dollar stores, which also often sell tobacco) be built at least one mile from any existing discount store unless they dedicate at least 500 square feet of floor space to the sale of fresh meats, fruits, and vegetables. This regulation is intended to limit the density of small box discount stores, which fail to provide fresh produce, instead offering pre-packaged and non-perishable foods high in sodium and sugar, while making it difficult for grocery stores to locate there, and to encourage access to fresh produce. The Healthy Neighborhoods Overlay Policy also allows the sale of food from local community gardens without approval from the Board of Adjustments, and reduces the parking space requirement for grocery stores built in North Tulsa, a food desert and food swamp, by 50% in order to reduce initial costs to opening a grocery store. Other cities, including Kansas City and Mesquite and Ft. Worth, Texas have also implemented policies that restrict the location of dollars stores in low-income neighborhoods.

Resources:

- ChangeLab Solutions’ Licensing for Lettuce: A model ordinance and guide for licensing healthy food retailers

- The Environments Supporting Healthy Eating (ESHE) Index Hub – The ESHE Index Hub is a useful and free tool that allow partners to create scores based on the community nutrition environment, organizational environment, food prices, and broader information environment. The tool also includes other aspects of the retail environment, such as location of retail outlets and restaurants, commercial advertisement, food beverage prices, low-income access to SNAP-authorized stores, and lastly, farmer’s markets. The purpose is to raise community awareness, through education and policy support for access to health foods in the community.

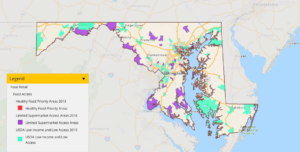

- Maryland Food System Map

- Berkeley Media Studies Group’s The 4 Ps of marketing: Selling junk food to communities of color

Alcohol

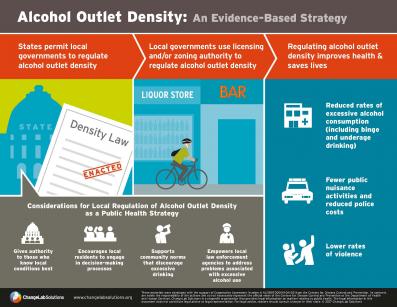

Greater alcohol outlet density has been linked to excessive alcohol consumption as well as increased injury, crime, and violence [7] – including higher rates of impaired driving and motor vehicle accidents,[8; 9] violent crime and assault,[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] unintentional injury,[15] alcohol consumption quantity,[7, 16] and underage drinking.[17, 18] National studies indicate that alcohol retailer density is also significantly higher in neighborhoods with greater proportions of non-White,[19] Black,[20] and Hispanic residents,[20] and in those with lower socioeconomic status,[19, 20] and greater neighborhood deprivation.[21]

Resources:

- CDC Guide for Measuring Alcohol Outlet Density

- Strategizer 55 – Regulating Alcohol Outlet Density: An Action Guide

- ChangeLab Solutions’ Alcohol Outlet Density Infographic

- Local Authority to Regulate the Density of Alcohol Outlets FAQs

For more on alcohol retail outlet density, view the recording of Counter Tools’ webinar on Alcohol at the POS: Places, Promotions, and Problems featuring Dr. Pamela Trangenstein below or download the slides.

Cannabis

Similar to the strong evidence around the impact of tobacco retailer density, researchers have identified an association between higher retail outlet availability and increased cannabis use,[22] including a higher likelihood of experimentation among youth.[23] Analysis also points to a higher concentration of cannabis retailers in already disadvantaged neighborhoods.[24]

Point-of-Sale Pricing Strategies

Tobacco

Raising the price of tobacco products is one of the most effective strategies for reducing initiation, decreasing consumption, and increasing cessation of tobacco. It is has a pro-equity effect on smoking, and raising excise taxes has long been the gold standard for raising the price of tobacco products.[25] Additional pricing strategies include setting minimum floor prices for tobacco products and prohibiting the redemption of coupons and other discounts or price promotions. Learn more here.

Food and beverages

Pricing strategies have also seen recent success in discouraging the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages as well as food products that are high in sugar, sodium, and saturated fat. Internationally, the country of Chile has created tax laws for food with high sugar-sweetened beverages and energy dense ultra-processed foods. On June 16th, 2016, a Chilean law passed increasing the tax on foods and beverages with high sodium, saturated fat, and added sugar by 18%.

Cities in the US that have passed their own taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages include: Boulder, CO, Philadelphia, PA, Berkeley, CA, Cook County, IL, San Francisco, CA, Oakland, CA, and Albany, CA. However, following Big Tobacco’s strategy of preemption, the beverage industry has also started trying to block local governments from passing laws that tax their products. In California, this push resulted in a 2018 law that preempts local governments from passing any new local beverage or food taxes for 12 years.

Another pricing strategy is to lower the cost of healthy foods through subsidies while increasing the price of unhealthy items. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that:

- for every 10% decrease in the price of fruits and vegetables, their consumption rose by 14% (and BMIs declined by 0.06 kg);

- for every 10% decreases in the prices of other healthy foods, their consumption increased by 16%;

- for every 10% increase in the price of sugar-sweetened beverages, their consumption decreased by 7%;

- for every 10% increase in the price of unhealthy fast foods, their consumption decreased by 3%.[26]

Other studies have also shown that taxes on processed meat, unprocessed red meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages and/or subsidizing on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds could reduce cardiovascular disease and diabetes and reduce disparities in these diseases by SES.[27]

Just as tobacco prices are often lower in lower-income communities and communities of color, pricing for food also varies by location. For example, some studies have shown that healthy food costs more while junk food costs less on Indian reservations, fueling health disparities.

Alcohol

Pricing policies can also have a substantial impact on alcohol consumption as well, and increasing excise taxes on beer, wine, distilled spirits have been recommended by the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Models have shown that increasing the alcohol tax could significantly reduce alcohol-related mortality, motor vehicle crash deaths, sexually transmitted diseases, violence, and crime. [28] Minimum unit pricing for alcohol has also been proposed internationally in Wales and Scotland.

Point-of-Sale Health Warnings

Tobacco

Tobacco

Health warnings displayed at the point of sale are a counter-advertising mechanism involving written, and sometimes pictorial (or “graphic”) warnings of the health impacts of tobacco use along with information about cessation services. There are three main types of POS health warnings: warnings on tobacco packaging, warnings on tobacco advertisements, and stand-alone health warning signs. Learn more here.

Food and Beverages

In 2015, San Francisco worked towards passing a law that required putting warning labels on soda beverages, warning the public that “Drinking with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay…” This law would have made it mandatory for warning labels to cover 20% of ads on billboards, posters, walls, bus shelters, and transit vehicles. When the law was presented in 2015, the industry sued, alleging that it was an infringement on their right to free speech. It was thereby ruled as a violation of commercial free speech. In 2019, the same law was reviewed again and the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the requirement for the label to take up 20% of the beverage packaging was “unjustified or unduly burdensome”. However, they did not take issue with the requirement for the waning label itself or the text, only the size of the warning label. This means that San Francisco can either try to justify the 20% requirement or propose a smaller warning label in the future. Learn more.

While warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages or other unhealthy items have not yet been implemented, they have seen international success. In Chile, warning labels are required on junk food items that contain high levels of saturated fat, sugar, salt, or calories, as well as on sugary beverages.

These type of warning labels can make a difference in purchasing behavior, for example, by reducing parents’ purchase of sugary drinks for their children. [29]

Alcohol

In addition to the Surgeon General’s warning, some argue that alcoholic beverage containers should also contain a health warning about the substance’s link to cancer.

Cannabis

Although there are no federally required health warnings for cannabis in the United States, most states that have legalized the sale of cannabis for recreational use have mandated specific health and safety warnings. For example, in the state of Oregon, recreational cannabis is required to have the following label: “For use only by adults 21 and older. Keep out of reach of children.” Research is still emerging on the possible effects of health and safety warnings on legally sold cannabis. Initial findings suggest that large, comprehensive warnings have the potential to reduce the appeal of cannabis products, including among young people. [30, 31] people. In one experimental study, researchers found that warnings about risks to cognitive development had the highest level of perceived effectiveness among a sample of young adults. [32]

Point-of-Sale Advertising

Tobacco

The NCI has demonstrated a causal relationship between exposure to tobacco advertisements and youth smoking uptake. Across multiple studies, research has shown that youth more frequently exposed to tobacco promotion are 60% more likely to have tried smoking and 30% more likely to be susceptible to future smoking.[1] In addition, tobacco industry marketing and advertising increases total cigarette sales, distorts youth perceptions about the availability, use, and popularity of cigarettes, fosters positive brand imagery, cues cravings and undermines quit attempts, and fuels tobacco-related disparities. Learn more here.

Tobacco companies spend billions on marketing and promotions at the point of sale each year. Some of this is spent on retailer incentives, which are often formalized in contracts or merchandising agreements with retailers. These contracts can dictate pricing, product placement, and the amount of advertising that must be displayed. Learn more in Deadly Alliance: How Big Tobacco and Convenience Stores Partner to Hook Kids and Fight Life-Saving Policies.

However, first amendment commercial free speech rights limit the ways that POS advertising can be restricted. While restrictions on the time, place, and manner of advertising are possible, the most common form of advertising restriction is to restrict ALL advertising without regard to its content – often called “content neutral” advertising restrictions. For example, localities may limit the percentage of window space that can be taken up by advertisements of any kind (including tobacco, alcohol, and junk food) or limit the size of advertisements allowed.

Food

Particularly in convenience stores and other small food stores, retailers often have contracts with tobacco companies and/or food and beverage suppliers that dictate much of how and where food and beverage products are priced, displayed, advertised within their stores. For food and beverages, these agreements can be either formal or informal. Learn more in this archived webinar: A Dive Into the Food Retail Environment.

The beverage industry has copied Big Tobacco’s playbook in more than one way. According to a report from The Guardian based on industry documents, when it comes to advertising products to kids, tobacco companies RJ Reynolds and Philip Morris “…adapted and sold their marketing strategies – including bright colors, flavors and memorable brand characters – to promote popular drinks such as Kool-Aid and Capri Sun to children…”

While there’s no fresh fruit and vegetable equivalent to the tobacco, food, and beverage industries, creative advertising for fresh fruits and vegetables can increase revenue from these products. [33] Combining promotion of healthy items in stores with prime product placement can also lead to an increase in sales of those healthy items [34]

Product Placement at the Point of Sale

Tobacco

Strategic placement of tobacco products is an integral component of the tobacco industry’s marketing scheme. The Federal Trade Commission reported that in 2016, the tobacco industry spent $257 million on promotional allowances to tobacco retailers to control the strategic shelving and placement of tobacco products. These displays increased perceived availability and accessibility of tobacco products, increase brand recognition, and encourage impulse purchases, which can undermine quit attempts.

Point of sale policies to address tobacco product placement include prohibiting self-service displays of any kind of tobacco — including little cigars, cigarillos, and e-cigarette products — and display bans are the two main avenues for restricting tobacco product placement at the point of sale. Though they have had success abroad, policies affecting product displays like “powerwalls” face unique legal challenges within the United States. Learn more here.

Food and beverages

Product placement does not just work for tobacco – the same principles apply when it comes other products as well, and prime placement can encourage impulse buys of foods and beverages. This is of concern when the items most commonly seen at checkout are candy, soda, and chips. For more on this, see the following resources from the Center for Science in the Public Interest:

- Roadmap and Tool Kit for a Healthy Checkout Ordinance

- Temptation at Checkout: The Food Industry’s Sneaky Strategy for Selling More

- How Grocery Store Agreements Impact Public Health

- CSPI Checkout Aisle Assessment Instrument

Read more in this article from The Counter: Why do Coca-Cola, Frito-Lay, and Mars get the best real estate in grocery stores? Because they pay for it.

Retailers can make voluntary changes to improve their checkout aisles, as will be discussed below, or communities can enact policies that require them to do so. See ChangeLab Solution’s Model Healthy Checkout Aisle Ordinance.

Alcohol

Stores often have beer in floor displays, beer and other alcoholic beverages placed in coolers or located near the checkout counter, and this type of product placement can influence the purchase of alcohol as well.[35]

Voluntary Healthy Retail Changes

Tobacco:

Retailers can support the health of their communities by creating more health-friendly environments for their shoppers. Some stores have even voluntarily decided to stop selling tobacco for various reasons, including health, ethical, business, and image-related reasons.[36]

When large retail chains decide to end tobacco sales, it can have a population level effect on tobacco use. CVS Health, a national pharmacy chain voluntarily announced they would no longer sell tobacco products in February 2014. By October 1st, 2014, more than 7,600 stores stopped selling cigarettes and tobacco products. Following the chain’s removal of tobacco products from its stores, total cigarette purchases in states where CVS holds significant market share declined by 1%, and smokers who had previously purchased their cigarettes exclusively at CVS were up to twice as likely to stop buying cigarettes entirely.[37] Walgreens is now piloting an end to tobacco sales in their stores, starting with all of their stores in the City of Gainesville, FL.

Some smaller chains and many independent retailers have also chosen to stop selling tobacco. For example, in 2015, the California grocery company Raley’s decided to stop selling tobacco. Shop-Rite in New Jersey ended their tobacco sales in 2014. Learn some of their reasons in the video below, featuring independent retailers in Vermont:

However, when chains decide to start selling tobacco, like Dollar General and Family Dollar did in late 2012 and early 2013, it can counteract other chains’ decisions to end sales,[38] which points to the need for policies that limit tobacco retailer density across communities, regardless of corporate action.

Voluntarily Eliminating or Reducing Tobacco at the POS: Nudges from Tobacco Control Policy

Other community level factors can also encourage retailers to end tobacco sales. For example:

- Increasing the price of tobacco. As tobacco prices rise, tobacco consumption goes down, which can mean fewer sales for retailers. For example, excise taxes in New York State went up from $1.50 to $2.75 in 2008 to and up again to $4.35 in 2010, which may have contributed to declining cigarette sales and led some retailers to voluntarily end tobacco sales.[39]

- High tobacco retailer licensing fees may encourage retailers to evaluate if selling tobacco is worth it to their business.[40, 41, 42]

- Providing retailers with incentives for ending tobacco sales or reducing the presence of tobacco in their stores. In 2007, a New York tobacco control coalition conducted a media campaign encouraging local tobacco retailers to reduce or remove tobacco advertising from their stores. When one of the stores stopped selling tobacco, they held media events and publicly thanked the stores for their decision.[43] The stores that stopped selling tobacco not only benefited their communities by reducing tobacco product availability, but also saw benefits themselves, including community recognition, improved cash flow, and improvements in public image.[44]

Food and Beverages

Retailers can voluntarily decide to implement healthy checkout aisles. For example in 2016, the regional grocery chain Raley’s announced they would begin to stock the check-out aisle with “better-for-you” products. Individual stores may choose to modify their check-out aisles as well. For example, a Walmart in Anderson, CA piloted healthy checkout aisles at the request of middle school students and afterwards decided to add more healthy checkout aisles. Learn more here:

- Case Study: U.K. Retailers Rethink Checkout

- Model Memorandum of Understanding Between Community Organizations and Stores for Healthy Checkout Lanes

Tobacco, Food, and Alcohol:

On a smaller, less formal scale, a group of high school students in Napa Valley, CA have worked with local retailers to increase signage about the legal age for tobacco and alcohol, adding signs pointing out healthy food options, and rearrange products to encourage healthier choices, moving cases of water to the front of the store and soda to the back.

Healthy Retail Program Examples

There are many different strategies and programs to help or encourage corner stores to sell healthier products. In some communities, particularly those in low-income and minority neighborhoods, there is a high prevalence of stores selling tobacco, alcohol, fast food, and few options for healthy, fresh food.

Administrative policies can encourage health retail environments. One of the first of these types of policies was implemented in Baldwin Park, CA. In 2008, the California Center for Public Health Advocacy (CCPHA), the Baldwin Park Resident Advisory Committee, and their partners worked with 14 stores on the “Healthy Selection Program” to help with the transformation of local corner stores. In 2012, the Baldwin Park Healthy Corner Store Policy was drafted, which helped local corner store owners provide and promote healthy foods, limit youth exposure to advertising for unhealthy products, and arrange the store to support healthy choices. Officially adopted as policy in 2014, it now includes a three-tiered, incentive-based approach. Learn more about these types of policies in ChangeLab Solution’s Health on the Shelf toolkit.

Other places have implemented their own healthy retail programs. For example, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health partnered with the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians and Counter Tools on a Tobacco-Free Retailer Pilot Project to help small businesses in low- and middle-income neighborhoods stop selling tobacco without losing revenue. The program provided participating stores with financial, technical, and small planning assistance to replace tobacco with healthy food products. Learn more:

- North Philly Shop Owner Helping Customers Make Healthy Choices

- Transitioning Away from Tobacco: Tips for Philly Retailers

Grassroots work by the Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition and South East Food Access resulted in the passage of a the Healthy Food Retailer Incentive Program Ordinance (“Healthy Retail SF”), which incentivizes small stores to stock more healthy foods and decrease the amount of tobacco and alcohol available in their stores. At the first four stores that participated, the changes resulted in a 35% increase in produce sales as well as declines in tobacco sales within the first year.[45] Learn more:

In any healthy retail program, it is important to consider the perspectives of the retailers and any previous challenges they may have faced with selling healthy foods as well as their own interests in supporting community health.[46]

More Healthy Retail Program and Policy Resources:

- ChangeLab Solutions’ resources on Healthy Retail, including:

- Healthy Retail SF: http://www.healthyretailsf.org/

- Healthy Corner Stores in Sonoma County: Healthy Food, Strong Partnerships, Good Policy

- CDC’s Healthier Food Retail Action Guide

- Creating Healthy Corner Stores: An analysis of factors necessary for effective corner store conversion programs

- The Food Trust’s Healthy Corner Store Initiative Overview

- Healthy Food Policy Project

- UCSF Food Industry Documents archive

- Healthy Eating Research

- Recommendations to Promote Healthy Retail Food Environments: Key Federal Policy Opportunities for the Farm Bill, Center for Science in the Public Interest