E-Cigarettes at the Point of Sale

The tobacco industry employs many of the same tactics to market e-cigarettes as they do to market other commercial tobacco products. However, the e-cigarette market is also in some ways unique and has grown tremendously in the past decade, with tobacco industry marketing leading to e-cigarettes becoming the most popular tobacco product among youth. While the federal regulatory landscape for e-cigarettes is still taking shape, in this evidence summary we take a look at the current retail landscape for e-cigarettes, factors of the retail environment that shape e-cigarette use, and regulatory options that can help minimize their harm.

The tobacco industry employs many of the same tactics to market e-cigarettes as they do to market other commercial tobacco products. However, the e-cigarette market is also in some ways unique and has grown tremendously in the past decade, with tobacco industry marketing leading to e-cigarettes becoming the most popular tobacco product among youth. While the federal regulatory landscape for e-cigarettes is still taking shape, in this evidence summary we take a look at the current retail landscape for e-cigarettes, factors of the retail environment that shape e-cigarette use, and regulatory options that can help minimize their harm.

What’s on this page?

- What are e-cigarettes?

- Prevalence

- Vape Shops

- Advertising at the Point of Sale

- Health & Safety Issues

- E-Cigarettes & FDA Regulation

- Policy Options

- Additional Resources

What are e-cigarettes?

E-cigarettes are battery-operated tobacco products designed to deliver nicotine, flavor, and other chemicals. They turn highly addictive nicotine and other chemicals into an aerosol that is inhaled by the user. However, the industry is rapidly evolving, and many variations and categories of these products exist, including tanks and mods, “pod mod” styles with cartridges, and disposable e-cigarettes. E-cigarettes are also known by different names, including “vapes,” “vape products,” “vaping products,” “electronic smoking products,” “vaporizers,” “mods,” “e-hookahs,” and “electronic nicotine delivery systems.” For the purposes of this evidence summary, we will loosely refer to the entire category of devices as e-cigarettes.

Definitions

Depending on how e-cigarettes are defined in a state or local policy, there may be different legal considerations and implications. E-cigarettes containing nicotine derived from tobacco are now considered tobacco products under FDA regulation. However, how state and local laws define e-cigarettes, and whether these products are categorized separately from other tobacco products will determine whether other existing regulations apply.[1] Comprehensive definitions should cover all e-cigarette products, including all types of e-cigarettes as well as their components and parts, regardless of the substance that is inhaled or its source, and are also broad enough to cover future e-cigarette products. Review the Public Health Law Center’s review of current e-cigarette regulations in all 50 states for more details on varying state definitions and regulations. Consulting with the Public Health Law Center or another legal center can also be helpful in drafting a comprehensive definition and assessing a current definition.

E-Cigarette Devices

There are many different types of e-cigarettes as the product category has evolved and expanded over time.

- 1st generation: These are disposable e-cigarettes that were designed with the same size and shape of a conventional cigarette to maintain the look and feel of smoking a cigarette. Often called “cig-a-likes” many have a tip that lights up when activated to mimic smoking.

- 2nd generation: These rechargeable e-cigarettes, often called “vape pens” these are comprised of a battery pen used with prefilled or refillable e-liquid cartridges that use free-base nicotine.

- 3rd generation: These rechargeable e-cigarettes (“mods” “tanks” and “sub-ohms”) are comprised of a device with modifiable voltage or watts and can be used with custom substances. These are designed to create large clouds of aerosol and to deliver a stronger “hit” of nicotine.

- 4th generation: These are e-cigarettes (also known as “pod mods”) can be comprised of either a prefilled or refillable cartridge called a “pod.” Popular brands include Juul, Suorin, and Vuse Alto. They also usually use nicotine salts, which have a lower pH and therefore can deliver a higher dosage of nicotine to the user without as much irritation. Many of these devices resemble USB flash drives, but they come in a range of shapes and sizes. Some new disposable e-cigarettes like Puff Bar are designed similarly to 4th generation pod mods, but the entire e-cigarette is disposable rather than just the “pod” or cartridge. These also use nicotine salts.

- Vaporizers, dab rigs, and dab pens are also electronic inhalant devices more often used for cannabis.

E-cigarettes can also be categorized into “open” and “closed” systems:

- Open systems are rechargeable devices that allow the user to add an e-liquid solution or loose-leaves into the system. They also allow the user to adjust the settings to personalize the devices. Mods are larger open-system devices, usually made of metal, which can be modified (hence the name “mod”) or rebuilt to fit customer preferences for battery size, voltage, temperature control, coils, etc. Herbal/dry chamber vaporizers are open-systems designed to heat loose-leaf plant material without burning it. These are marketed to create a “cleaner” high than traditional forms of smoking, and are often used for marijuana. They are sold as a pen style, portable style, or desktop style.

- Closed systems are those that cannot be taken apart, have the tank refilled, or be altered by the user. They can be disposable or rechargeable. Some, like Juul and other “pod mods“ allow the user to replace cartridges. Cig-a-likes and pre-filled vape pens or vape sticks also fall into this category. For more information on the different categories of e-cigarette devices and images of each, please visit our vSTARS Training Manual.

Learn more from the CDC’s E-cigarette, or Vaping, Products Visual Dictionary and in Truth Initiative’s Vaping Lingo Dictionary.

E-liquid solutions and flavors

Similar to the difficulty in naming e-cigarettes, the liquid solutions used inside of the e-cigarettes also carry a myriad of undefined labels, including “e-juice”, “e-liquids,” and “e-liquid solutions.” These liquids are used in all types of e-cigarette devices except for the open-system, dry-chamber, herbal vaporizers. E-liquid solutions usually contain nicotine and flavors which are then added to a base of propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin. They also may or may not contain caffeine, THC, CBD, or other psychoactive substances dissolved into a liquid base.

Similar to the difficulty in naming e-cigarettes, the liquid solutions used inside of the e-cigarettes also carry a myriad of undefined labels, including “e-juice”, “e-liquids,” and “e-liquid solutions.” These liquids are used in all types of e-cigarette devices except for the open-system, dry-chamber, herbal vaporizers. E-liquid solutions usually contain nicotine and flavors which are then added to a base of propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin. They also may or may not contain caffeine, THC, CBD, or other psychoactive substances dissolved into a liquid base.

The endless variety of flavors available for e-liquid solutions pose a particular problem for youth initiation. A study in 2014 found a total of 7,765 flavors and 466 brands, and the market has only grown since then.[2] Common flavors with a strong youth appeal include fruit flavors (e.g. cherry, blueberry, melon) and candy flavors (e.g. cotton candy, bubblegum, chocolate, and vanilla). An increasing number of e-liquid solutions have names that do not reflect the precise flavoring, such as “Lizard Guts” or “Unicorn Puke”. Similarly, most major e-liquid manufacturers create menthol e-liquid solutions, which are often labeled as mint, wintergreen, ice, or frost. Also common are e-liquid solutions that share the same flavor profiles as alcoholic beverages, such as “sex on the beach” or “mojito.” While the FDA has prohibited the sale of flavored cartridge-based (closed-system) e-cigarette products other than menthol or tobacco flavor, that restriction does not include e-liquids. However, many state and local policies do restrict or prohibit their sale.

With the introduction of Juul to the market, nicotine concentrations rose from an average of 2.19% in 2013 to 4.34% in 2018.[3] Many brands on the market now contain even higher concentrations. These greater nicotine concentrations increase the risk of nicotine addiction and subsequent health consequences, especially for youth, whom these high-nicotine concentration products are popular with, and who may not realize that the products contain nicotine at all. [4]

E-liquid solutions that do not contain any nicotine are often marketed as a “healthy” alternative to smoking or vaping nicotine, particularly if these e-liquid solutions contain vitamins, such as the 0-nicotine VitaVape products. However, the health claims on these “wellness vapes” are unproven, the products are unregulated, and may still cause respiratory issues. These zero-nicotine e-cigarettes also comprise less than 1% of the market.[5][6]

New lines of e-liquids are emerging that are labelled as TFN (Tobacco-Free Nicotine). These e-liquids contain nicotine allegedly not derived from tobacco plants. The FDA gained authority to regulate synthetic or non-tobacco nicotine as tobacco in April 2022. Comprehensive policy language at the state and local level can also intentionally define products broadly, so that restrictions on e-cigarettes can encompass both zero-nicotine solutions and nicotine derived from sources other than tobacco.

Prevalence

Youth E-Cigarette Use

E-cigarettes first entered the US market in 2007, became the most popular tobacco product among youth in 2014 and remain so as of 2021.[7] According to the National Youth Tobacco Survey [NYTS], current (past 30-day) use of e-cigarettes among youth doubled between 2011 and 2012,[8] and tripled among youth from 2013 to 2014.[9] While current e-cigarette use declined among middle and high school youth from 2015 to 2016,[10] between 2017 and 2018, current e-cigarette use grew by 78% among high school students and by 48% among middle schools students, driven largely by new USB-shaped e-cigarette product Juul.[11] This prompted the Surgeon General to issue an Advisory on E-cigarette Use Among Youth, calling it an epidemic. Data from the 2019 NYTS showed that 53.3% of US high school students had ever used a tobacco product with approximately 27.5% of high school students reporting current e-cigarette use. [12] The 2020 NYTS showed some promising decline in youth vaping rates. From 2019 to 2020, current e-cigarette use in high school students dropped from 27.5% to 19.6% and in middle school students from 10.5% to 4.7%.[13] However, data from the 2021 NYTS (conducted online) showed that even during the Covid-19 pandemic with many students at home, over 2 million middle and high school students reported using e-cigarettes, with 11.3% of high school students and 2.8% of middle school students reporting current e-cigarette use. [14] Disconcertingly, over a quarter (27.6%) of high school students and 8.3% of middle school students who use e-cigarettes reported using them daily. [14] The 2022 NYTS (also conducted online), showed a rise in current youth use in e-cigarettes with 14.1% of high school students and 3.3% of middle schools students reporting use in the past 30 days. However, the 2023 NYTS showed a drop in current e-cigarette use, with 10% of high school students reporting current use. Daily use remains a concern, with again 25.2% of youth e-cigarette users reporting daily use. Findings from the 2024 NYTS show a decline in U.S. middle and high school students who reported current (past 30 days) e-cigarette use at 1.63 million compared to 2.13 million in 2023. Of current youth e-cigarette users, 26.3% reported daily use and 54.6% use flavors with “ice” or “iced” in the name.

E-cigarettes first entered the US market in 2007, became the most popular tobacco product among youth in 2014 and remain so as of 2021.[7] According to the National Youth Tobacco Survey [NYTS], current (past 30-day) use of e-cigarettes among youth doubled between 2011 and 2012,[8] and tripled among youth from 2013 to 2014.[9] While current e-cigarette use declined among middle and high school youth from 2015 to 2016,[10] between 2017 and 2018, current e-cigarette use grew by 78% among high school students and by 48% among middle schools students, driven largely by new USB-shaped e-cigarette product Juul.[11] This prompted the Surgeon General to issue an Advisory on E-cigarette Use Among Youth, calling it an epidemic. Data from the 2019 NYTS showed that 53.3% of US high school students had ever used a tobacco product with approximately 27.5% of high school students reporting current e-cigarette use. [12] The 2020 NYTS showed some promising decline in youth vaping rates. From 2019 to 2020, current e-cigarette use in high school students dropped from 27.5% to 19.6% and in middle school students from 10.5% to 4.7%.[13] However, data from the 2021 NYTS (conducted online) showed that even during the Covid-19 pandemic with many students at home, over 2 million middle and high school students reported using e-cigarettes, with 11.3% of high school students and 2.8% of middle school students reporting current e-cigarette use. [14] Disconcertingly, over a quarter (27.6%) of high school students and 8.3% of middle school students who use e-cigarettes reported using them daily. [14] The 2022 NYTS (also conducted online), showed a rise in current youth use in e-cigarettes with 14.1% of high school students and 3.3% of middle schools students reporting use in the past 30 days. However, the 2023 NYTS showed a drop in current e-cigarette use, with 10% of high school students reporting current use. Daily use remains a concern, with again 25.2% of youth e-cigarette users reporting daily use. Findings from the 2024 NYTS show a decline in U.S. middle and high school students who reported current (past 30 days) e-cigarette use at 1.63 million compared to 2.13 million in 2023. Of current youth e-cigarette users, 26.3% reported daily use and 54.6% use flavors with “ice” or “iced” in the name.

Youth use of e-cigarettes is concerning because of the potential for nicotine addiction, the harms of nicotine use on adolescent brain development, the harms of other substances contained in the inhaled e-cigarette aerosol, and the link between e-cigarette use and subsequent use of more harmful tobacco products. A meta-analysis concluded that young adults who used e-cigarettes were over 4 times as likely to smoke cigarettes in the future than those who never used e-cigarettes.[15]

In addition to targeted marketing, flavors are a key driver of youth e-cigarette use. The 2023 NYTS survey shows that nearly 90% of youth who use e-cigarettes use flavored varieties, with the most commonly used flavors being fruit (63.4%) and candy (35.0%), while only 6.4% reported using tobacco flavor. In addition, among youth who reported using disposable e-cigarettes, the most commonly used e-cigarette type among youth, the most popular types of flavors were: fruit (70.5%), candy (39.8%), mint (32.0%), and menthol (18.7%), with lower rates of use for unflavored (7.8%), alcoholic drinks (7.2%), and tobacco-flavored (5.4%).

Youth e-cigarette product use is responsive to regulation. Many youth have pivoted from using pre-filled pods and cartridges like Juul, which were banned in flavors other than menthol and tobacco at the beginning of 2020, to using disposable e-cigarettes, which are still available in a variety of flavors. In fact, rates of disposable e-cigarette use among high school students skyrocketed from 2.4% in 2019 to 26.5% in 2020. By 2021, disposables were the most popular type of e-cigarettes, with Puff Bar emerging as the most popular brand. In 2022, Puff Bar remained the most popular brand, followed by Vuse and Hyde. In 2023, following regulation of synthetic nicotine that brands like Puff Bar switched to, the most popular brands shifted to Elf Bar, Esco Bars, Vuse, JUUL, and Mr. Fog..

This shift to the products that remain flavored is also evident in sales data, with the market share of disposable e-cigarettes growing from 25.0% in 2020 to 27.5% in 2021, and among disposable e-cigarettes, the market share for flavors other than tobacco, menthol or mint increased from 69.2% in 2020 to 79.4% in 2021. Learn more about policy options for restricting the sale of flavored e-cigarettes.

Learn more about youth e-cigarette use here:

- 2016 Surgeon General’s Report: E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults

- CDC’s Quick Facts on the Risks of E-cigarettes for Kids, Teens, and Young Adults

- Public Health Law Center’s

- Public Health Concerns About Youth & Young Adult Use of Juul

- Juul & The Guinea Pig Generation

- Juul & The Guinea Pig Generation: Revisited

- Archived webinar: What’s the Hype? JUUL Electronic Cigarette’s Popularity with Youth & Young Adults

- Archived webinar: What We Can Do To Rein in JUUL: A Policy Discussion

- Truth Initiative’s fact sheets:

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids’ Juul and Youth: Rising E-Cigarette Popularity

- SAMHSA’s Reducing Vaping Among Youth and Young Adults

Adult E-Cigarette Use

Adult use of e-cigarettes is much lower than youth use, it is the second most commonly used tobacco product among adults in the US, with 4.5% of US adults reporting current use in 2019; Of those adults who reported using e-cigarettes, 36.9% also currently smoked cigarettes, 39.5% formerly smoked cigarettes, and 23.6% had never smoked cigarettes. [16] However, rates are much higher among younger adults (9.3%), adults who are LGBTQ+ (11.5%) and those who have chronic health conditions [17, 18]

Conflicting evidence exists in the literature on whether e-cigs help or undermine quit attempts. The United Kingdom’s Royal College of Physicians has publicly stated that they believe evidence shows that the benefits of e-cigarettes outweigh the harms. Some research suggests the effectiveness of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, while evidence has also surfaced that e-cigarettes are no more effective than alternative smoking aids, and rather may lead to more long-term nicotine dependence and possible relapse to cigarette smoking.[19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24] They are not an FDA-approved cessation aid; however, the CDC notes that “E-cigarettes have the potential to benefit adults who smoke and who are not pregnant if used as a complete substitute for regular cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products.”

For more information, review the following:

- Truth Initiative’s Statement on Harm Reduction

- Smokers Urged to Switch to E-Cigarettes by British Medical Group

- The Lancet: E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Cochrane Review: Can electronic cigarettes help people stop smoking or reduce the amount they smoke, and are they safe to use for this purpose?

- Cochrane Review: Conclusions about the effects of electronic cigarettes remain the same

Vape shops

While e-cigarettes are sold in most places other tobacco products are sold, including convenience stores, grocery stores, mass merchandisers, pharmacies and other stores, they are also sold at vape shops, which have a unique retail environment. Vape shops accounted for nearly 20% of the e-cigarette market in 2019. A vape shop sells products such as vape pens, tanks, mods, e-juices, e-hookahs, advanced systems, and their accompanying components along with e-liquid solutions or cartridges. These stores may or may not have a vaping lounge or vaping bar inside as well. Many vape shops operate on non-traditional retail hours, opening closer to noon and closing later at night. Head shops have also started carrying advanced, open-system e-cigarettes in addition to other smoking-related paraphernalia, usually related to recreational drug use (e.g., bongs, glassware, incense). A study conducted in 6 major metropolitan areas in the US found that vape shops were where adults who use e-cigarettes mostly commonly obtained e-cigarettes (44.7%).[25]

Vape store customers may also differ from those who obtain their e-cigarettes through other channels. A survey conducted between 2014-2016 comparing e-cigarette users’ behaviors based on their primary place of purchase found that vape shop customers were the most likely to be daily users (59.1%) and former smokers (40.2%), followed by internet customers.[26] Vape shop and internet customers were also most likely to have made an attempt to quit smoking cigarettes in the past 12 months, but retail store customers were most likely to have used an FDA-approved cessation aid. The large majority of vape shop customers (92.8%) used open-system models.[27]

As vape shops strive to create a unique retail environment, they have promoted certain messages to customers in an attempt to differentiate their products from combustible cigarettes and other tobacco products. Although research on vape shops is still limited, a 2014 study reflects the anecdotal evidence that most vape shop owners (76%) believe that their products are a safer alternative to cigarettes.[28] This belief is often conveyed via posters inside vape shops that convey harm reduction messages about vaping, along with staff’s personal testimonials. Modified risk claims that are not approved by the FDA are prohibited under the deeming rule. Many vape shops also purport the theory that vaping saves money when compared with smoking conventional cigarettes. To further the perceived economic benefits to vaping, stores will offer individual discounts to active duty or former military members or college students.

Similarly, many vape store owners or staff members claim that vaping is an effective method of smoking cessation, and they may use signs or images to depict this theory inside their store, along with sharing personal testimonials of how e-cigarettes helped them to stop smoking. While marketing e-cigarettes as cessation aids is illegal under federal law, a study of North Carolina vape shops showed that many vape shops still display signs with these claims.[29] These claims are also espoused on the websites of some brick-and-mortar vape shops. [75, 77]

Many vape shops take great lengths to differentiate themselves from traditional tobacco retailers, and as such, a different type of store assessment is needed to describe the store environment and marketing practices used. To this end, SCTC researchers, state, and local practitioners collaborated to develop the Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings: Vape Shops (vSTARS) surveillance tool, designed for practitioners to inform state and local tobacco control policies for the point of sale. The assessment items (e.g., types of products sold, flavors, health messaging) were selected exclusively for their policy relevance. No items function as compliance checks for federal regulations. This user-friendly tool can be filled out by professionally-trained data collectors, as well as self-trained adults. Learn more about tracking vape shops, how to use the tool, and download the materials here.

However, with federal regulation of e-cigarettes in place and an uncertain future as many remain under premarket review, some vape shops are now shifting to smoke shops (that sell both vape products and other tobacco products and accessories), diversifying their offerings to include a variety of tobacco products and (un- or under-regulated) cannabis-based products as well as kratom, as well as a growing their online retail segment, which can undermine federal, state and local restrictions on product sales in the retail environment, including youth access.[73]

Vape shops should be included in tobacco control compliance and enforcement efforts. While many theoretically restrict entry to adults 21+, that often is not well enforced. Data from the 2018 California Tobacco Control Program’s Young Adult Tobacco Purchase Survey, which uses 18-19-year-olds as underage decoys to attempt to purchase either cigarettes or vape product, found that about half (49.8%) of tobacco and vape shops that primarily sell tobacco products did not check IDs for the youth, and 44.7% sold to them.[30] The rates of sales to underage youth in these types of stores was significantly higher than in other types of stores.[31] Even after implementation of California’s policy raising the minimum age of sale for tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) to 21, most underage youth were purchasing their e-cigarettes from vape shops.[32] Another study that used mystery shoppers to examine regulatory compliance in 30 randomly selected vape shops in six US cities found that while nearly all shops displayed minimum-age signage either to enter to store or to purchase products, only about a third of shops asked for age verification upon entry and less than a quarter of shops asked for age verification upon purchase. [33] As well, 16% of vape shops offered free samples of e-liquids and 29% had signage with prohibited health claims. [33] This underscores the need for strong age-verification requirements and strong enforcement efforts, including, as study authors suggest, an increase in the number and frequency of FDA compliance checks.

Research has also revealed socioeconomic disparities in vape shop density and proximity, especially in relation to schools. One study found that school districts with higher proportions of Asian and Black populations had a greater density of vape shops, and more vape shops in close proximity to schools.[34]

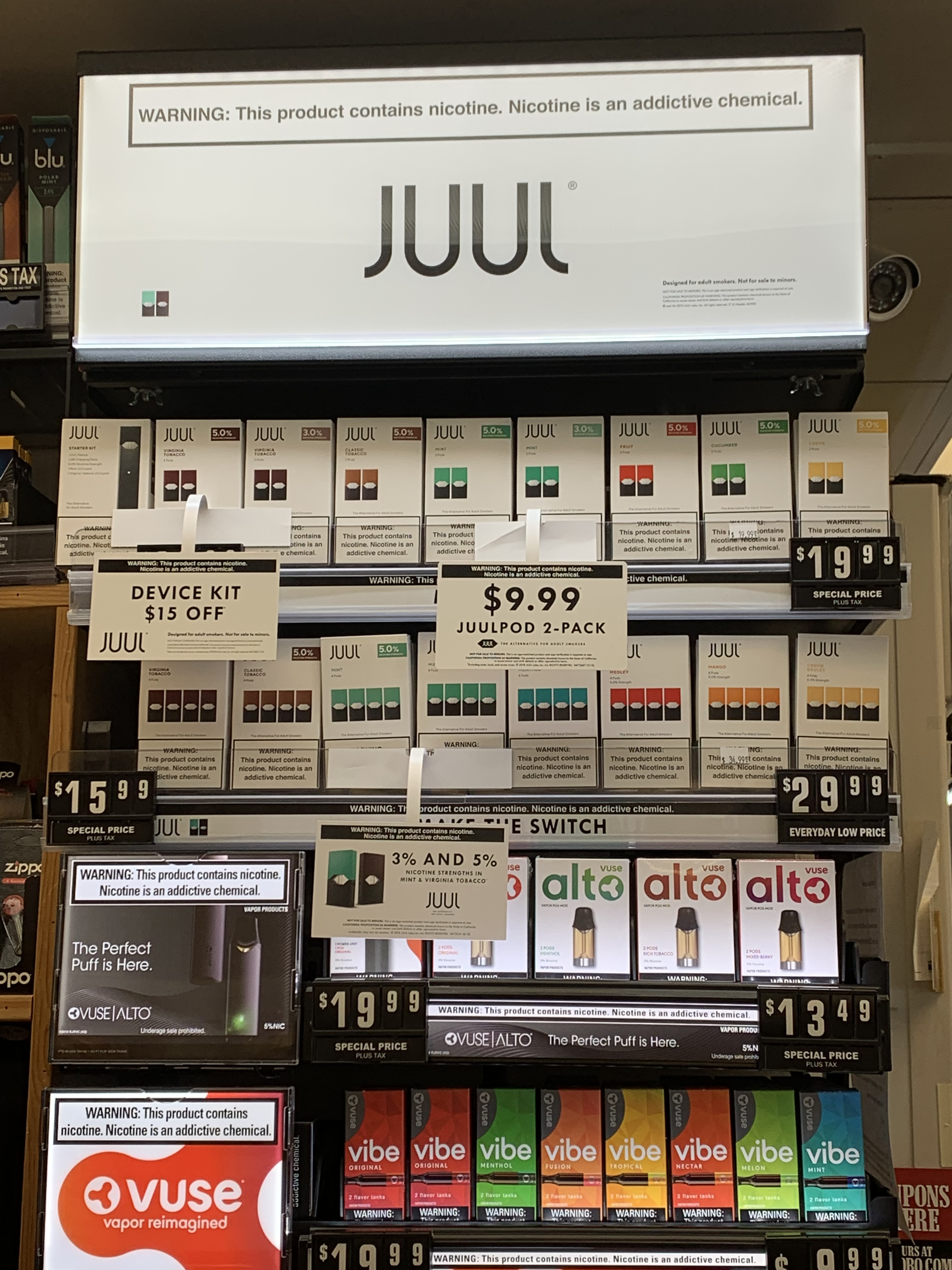

Advertising at the Point of Sale

The tobacco industry heavily advertises e-cigarettes, relying on similar advertising strategies that have proven effective with traditional cigarettes, including marketing to youth. The Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids outlines some of these tactics in 7 Ways E-Cigarette Companies are Copying Big Tobacco’s Playbook. The tobacco industry has begun to channel vast sums of money into the marketing of e-cigarettes. A 2013 study found that of noncombustible tobacco products, advertisements for e-cigarettes were the most widely circulated.[35] In 2017, e-cigarettes were the second most commonly advertised product on tobacco retailer exteriors, only behind cigarettes.[74] In 2018, tobacco industry giant Altria invested $38 billion for a 35% stake in the e-cigarette company Juul.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has issued reports on tobacco companies’ marketing expenditures for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco for decades; however starting in 2022, the agency began issuing reports on the sale and marketing expenditures of major e-cigarette companies as well. The first report, published in March 2022, contained information on the sales, advertising, and promotional activities from 2015-2018 from 6 e-cigarette companies who were then leading manufacturers: Fontem US, Inc.; JUUL Labs, Inc.; Logic Technology Department LLC; NJOY, LLC; Nu Mark LLC; and R.J. Reynolds Vapor Company) See our summary here. The second report, covering data from 2019-2020, was published August 31, 2022 and covered data from the five e-cigarette companies previously reported on that were still selling e-cigarettes (Nu Mark stopped manufacturing and distributing e-cigarettes at the end of 2018). See our summary here. The third report, issued in April 2024, focused on data from nine leading manufacturers in 2021, including the five companies previously reported on, which mostly manufacture and sell cartridge-based e-cigarettes. The four additional companies, which primarily manufacture and sell disposable e-cigarettes, include: Breeze Smoke, LLC; Kavival Brands Innovation Group, Inc; Pop Vapor Co., LLC; and PVG1, LLC (which markets Puff Bar e-cigarettes). The FTC noted that while these four companies were likely some of the leading marketers of disposable e-cigarettes, the market for those products is much more fragmented than the market for cartridge-based products, so the report is likely less representative of the disposable market. The report also contains corrected data for 2019 and 2020 as well as 2020 data from the four additional companies not covered in previous reports. Key findings include:

- E-cigarette companies spent $859.4 million on advertising and promotion in 2021, an increase of $90.6 million from 2020. Most of this spending came from the five leading cartridge-based e-cigarette manufacturers, while less than $500,000 of these expenditures were on disposable e-cigarettes.

- Over 84% of all e-cigarette advertising expenditures were focused on the retail environment, with the largest categories for expenditure being price discounts, promotional allowances, and point-of-sale advertising. This spending mirrors the pattern we see with marketing expenditures for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, for which the vast majority is also spent in the retail environment. Here’s what e-cigarette companies are they’re spending their marketing dollars on:

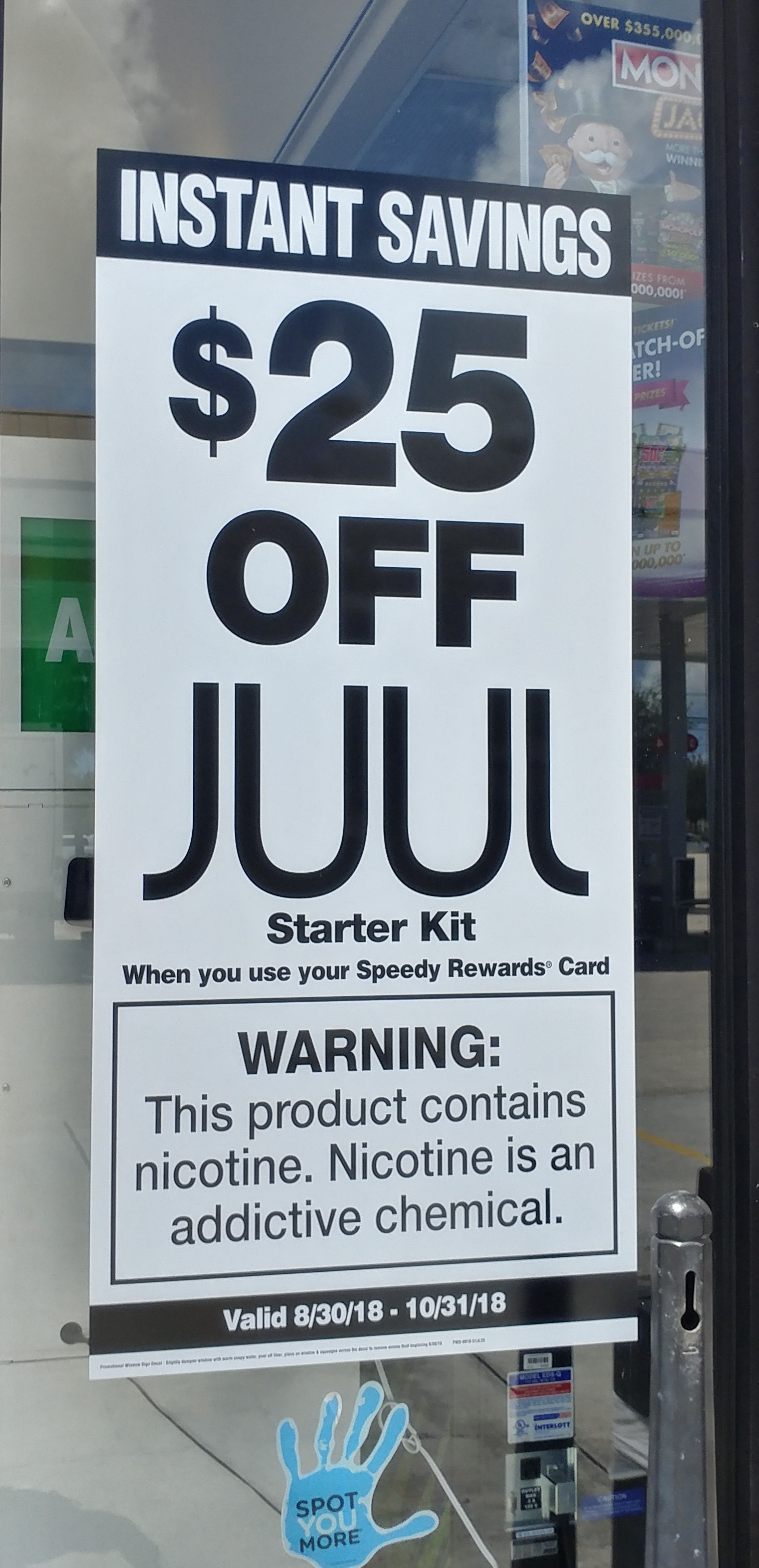

- Price discounts: This is the single largest category of spending, totaling $261.6 million in 2021. It includes payments to retailers and wholesalers to reduce the price of e-cigarettes to consumers. Price discounts also lead to higher rates of tobacco use among youth.

- Promotional allowances paid to retailers totaled $76.6 million in 2021. This can include payments for stocking, shelving, displaying, and merchandising brands, slotting fees, volume rebates, incentive payments, and the cost of e-cigarette products given to retailers for free for subsequent, resale to consumers.

- Promotional allowances paid to wholesalers totaled $194.8 million in 2021. This can include payments for volume rebates, incentive payments, value-added services, promotional execution, and satisfaction of reporting requirements.

- Point of Sale Advertising expenditures totaled $96.5 million in 2021. This includes any advertising displayed or distributed at a physical retail location.

- Coupons are another way e-cigarette companies reduce the price of their products to consumers, and they spent $27.4 million on coupons in 2021.

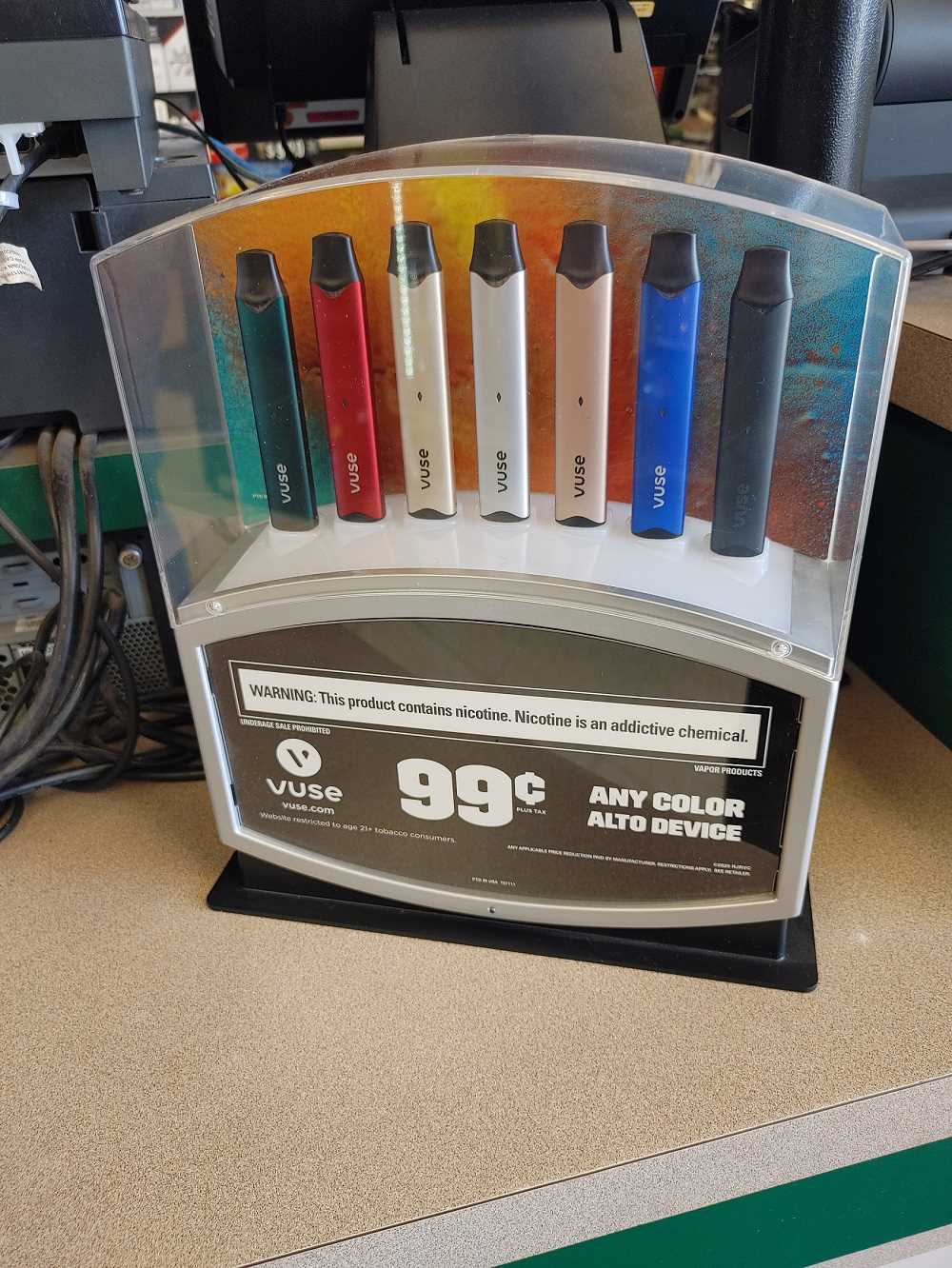

- Sampling expenditures totaled $59.5 million in 2021. This includes the distribution of free e-cigarette products and the distribution of e-cigarette products sold at a price of $1 or less. Note that many companies offer products at $1 or less to get around the FDA’s 2016 ban on free samples.

Since they began selling e-cigarettes, tobacco companies have marketed the products to youth. The report, “Gateway to Addiction? A Survey of Popular Electronic Cigarette Manufacturers and Targeted Marketing to Youth,” found major e-cigarette companies take part in marketing strategies that target youth through promotional activities like sponsorships or free samples at youth-oriented events and TV ads. However, a study by the Truth Initiative found youth awareness of e-cigarette advertisements to be highest at retail locations such as convenience stores, gas stations, and supermarkets. In 2016, 7 out of 10 middle- and high-school students were exposed to e-cigarette advertisements in the retail setting, representing a 24% increase in youth exposure since 2014. Research shows this marketing works and youth exposure to it is having an impact on youth e-cigarette use. A randomized controlled trial found that young adults who were exposed to e-cigarette advertisements had greater curiosity about, and were twice as likely to have tried e-cigarettes six months later than young adults who were not exposed to e-cigarette advertisements.[37] Similarly, a study conducted among 12-17-year-old students in Texas found that students who recalled seeing e-cigarette advertisements in stores were three times as likely to have ever-used e-cigarettes 6 months later compared to those who did not recall seeing e-cigarette advertisements in stores.[38] A study of Scottish youth found that those who recalled seeing e-cigarettes in retail settings were nearly twice as likely to have tried an e-cigarette, and also more likely to report intentions to try them within the next six months.[39] Evidence has also shown e-cigarette advertisements with visual depictions to increase the urge to smoke a traditional cigarette among daily smokers and reduce intentions to remain abstinent among former smokers.[40]

A study in New Jersey found higher rates of e-cigarette use among youth who attend schools located in areas with higher amounts of advertising for e-cigarettes within a half-mile compared to those in schools with less advertising nearby. [41] Some studies have also shown youth exposed to e-cigarette ads were also more likely to later try combustible tobacco products like cigarettes and cigars. [42]

Exposure to e-cigarette ads is harmful for adults as well. A 2016 study found that exposure to ads triggers cravings for traditional cigarettes among current smokers and reduced intentions to remain abstinent among former smokers.[43]

Evidence is still emerging on the patterns of e-cigarette advertising concentration and any disproportionate impact on already marginalized populations; however emerging evidence does show that similarly to other tobacco retailers, e-cigarette retailers and e-cigarette advertisements at the point of sale may be more concentrated in neighborhoods with a greater proportion of people of color. A national study found that in 2015, exterior advertisements for e-cigarettes were more prevalent in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of Black residents.[44] A 2020 systematic review found that e-cigarette advertisements were more prevalent in non-White neighborhoods.[45] However, patterns may vary based on a given location’s demographic breakdown. A study from Omaha, NE in 2014 found greater e-cigarette advertising density in higher income areas and in areas with more people who are non-Hispanic white.[46, 47] A study in California from 2016-2017 also found that compared to retailers in Non-Hispanic White communities, retailers in communities predominately comprised of other racial and ethnic backgrounds were less likely to sell e-cigarettes and flavored e-cigarettes, have self-service displays, and place e-cigarette products near youth-friendly items. As well, compared to Non-Hispanic White communities, retailers in Korean-American and Hispanic/Latino communities were less likely to have exterior advertising of e-cigarettes.[48] A study assessing the availability and promotional tactics of cigarettes and e-cigarette products on and within a 1-mile radius of California Tribal lands found that stores that were within a 1 mile radius, not directly on Tribal lands, sold significantly more e-cigarettes (70% compared to 38%), including of the flavored variety, and also more commonly offered price promotions for cigarettes (47% of stores vs. 23% of stores).[49]

Health & Safety Issues

Although e-cigarettes are likely safer than smoking combustible cigarettes, there are still demonstrated health risks to vaping due to chronic nicotine use, inhaled particulate matter, and toxic chemicals of certain e-liquid solutions, as well as unknown long-term health impacts. While it has been established that nicotine has adverse effects on the developing brain, other issues, like whether or not e-cigarettes are an effective method of harm reduction, are still debated.[50] Research is still emerging in the area of e-cigarettes and health, but some of the risks are outlined below.

One of the most obvious health issues with any nicotine product, including e-cigarettes, is the risk of developing addiction. This is of particular concern with 4th generation e-cigarettes that contain high concentrations of nicotine.

In addition to addiction, chronic nicotine use has been linked to cardiovascular, respiratory, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal disorders.[51, 52, 53, 54] Also of note, certain flavors of e-liquid solutions containing diacetyl can cause a disease, bronchiolitis obliterans, commonly referred to as “popcorn lung”. One Harvard study showed that 75% of all e-cigarettes had diacetyl within the e-liquid solutions.[55] Similarly, cinnamon flavored e-liquids, particularly those containing innamaldehyde, are cytotoxic, despite being safe for oral consumption.[56]

While the health of people who smoke may improve if they switch entirely to e-cigarettes, continuing to use both cigarettes and e-cigarettes poses unique health risks with exposure to different toxicants from each product, and may result increased respiratory symptoms.[57]

E-cigarette devices have been linked to explosions from lithium-ion batteries, small fires, and overheating.[58]

In 2019, the FDA began investigating reports of seizures, mostly among youth and young adults, suspected to be linked to vaping and nicotine poisoning. In addition, severe lung injuries and deaths have been linked to the use of electronic cigarettes with Vitamin E acetate, often used in vape products containing tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Learn more about EVALI, the e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury from the CDC.

E-Cigarettes & FDA Regulations

In 2016, the FDA extended their regulatory authority over e-cigarettes, bringing them under the definition of “tobacco product” and the provisions of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act through the “deeming rule.” The FDA also passed a number of regulations as part of this rule that impacted e-cigarette manufacturing, marketing, and sales. These included regulating modified risk claims, requiring disclosure of ingredients, prohibiting the use of “light”, “mild”, “low” or similar descriptors, and requiring the disclosure of harmful and potential harmful constituents, and more. One of the most important requirements imposed on e-cigarettes was the requirement for premarket review.

Premarket Review

Premarket review requires any new tobacco product not on the market as of August 8, 2016 (which means most e-cigarettes) to submit an application to the FDA for marketing authorization. The application deadline was delayed several times, and the date after which products without marketing authorization from the FDA can remain on the market moved from the originally planned August 8, 2016 to September 9, 2021. This final deadline was only set after several public health groups sued the FDA for neglecting their duty and a federal judge ordered the FDA to move forward the process. In order for the FDA to authorize a tobacco product to be marketed in the US, the FDA must decide the product is “appropriate for the protection of public health,” weighing both the risks and benefits of the product to the population as a whole, including users, non-users, and youth.

So far, the FDA has issued marketing denial orders for over 1 million products and granted marketing authorization for only 27 tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes. Their initial limited enforcement actions against products that remain on the market without authorization focused on products that most egregiously targeting youth. In total as of June 2024, the FDA has sent over “1,100 warning letters to manufacturers, importers, distributors and retailers for illegally selling and/or distributing unauthorized new tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, and has filed civil money penalty complaints against more than 55 manufacturers and 140 retailers for the manufacture and/or sale of unauthorized tobacco products. In addition, the FDA and the Justice Department have obtained injunctions against six manufacturers to stop them from manufacturing and selling unauthorized e-cigarette products.” In June 2024, the agency launched a new task force that will take aim at the sale and distribution of illicit e-cigarettes. For more on the FDA’s premarket review process for e-cigarettes, see the Public Health Law Center’s factsheet, “Extensions and Epidemics: The FDA’s Gatekeeping Authority for E-Cigarettes” and see updates on the FDA decisions on their Tobacco Product Applications: Metrics & Reporting page as well as on their Tobacco Product Marketing Orders page.

E-Liquid Mixing at Vape Shops

Prior to FDA “deeming”, a number of vape shops created their own e-liquid solutions onsite by mixing propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin with nicotine, flavors, or colors. Other shops allowed store staff to mix existing e-liquids to create new flavors onsite (e.g., mixing a chocolate flavored e-liquid with a strawberry e-liquid to create a new chocolate-strawberry flavor). Since the FDA regulations were signed, if a vape shop “mixes or prepares e-liquids or creates or modifies aerosolizing apparatus for direct sale to consumers for use in ENDS, the establishment fits within the definition of ‘tobacco product manufacturer’.” These tobacco product manufacturers are subject to more stringent regulations than vape shops that only sell pre-fabricated e-liquid solutions.

Warning Labels

As of May 2016, FDA regulations now require all newly-deemed products to have health warnings that state, “WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical.” For products that do not contain nicotine at detectable levels, the warning is revised to read: “This product is made from tobacco.” E-liquid solutions that do not contain tobacco or nicotine, or are not derived from tobacco or nicotine, do not meet the definition of a “covered tobacco product” under the new FDA Deeming regulations, and they will not be required to carry an addiction warning. Some states also require health warnings or ingredient lists on e-liquid packaging, an approach which a 2014 public opinion poll showed two-thirds of adults support. [59]

Flavors

In November 2018, the FDA announced their intention to create a new policy framework that would restrict the sale of any flavored electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) other than tobacco, mint, or menthol flavors to age-restricted retail locations only. This would include e-liquids, cartridge-based systems, and cig-a-like products. Vape shops or other age-restricted retail stores would still be able to sell flavored e-cigarettes. Before the FDA outlined what this would look like, the e-cigarette company Juul began to implement new standards of their own, removing their flavors other than mint, menthol, and wintergreen from most retail stores in October 2018 and removing mint flavors in November 2019. On March 13, 2019, the FDA issued a draft compliance policy for flavored e-cigarettes and flavored cigars. However, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb left his post the following month. In response to rising youth e-cigarette use, on September 11, 2019, the Trump administration announced a future ban on the sale of flavored e-cigarettes, but final guidance from the FDA, issued January 2, 2020, only prohibits the sale of flavored cartridge-based (closed system) e-cigarette products other than menthol or tobacco flavor and does not apply to e-liquids or popular disposable e-cigarettes like Puff Bar. Unfortunately, data shows that youth will use any flavor left on the market. The 2023 NYTS survey shows that nearly 90% of youth who use e-cigarettes use flavored varieties, with use shifted largely to flavored disposable e-cigarettes as well as some cartridge-based menthol flavors.

Policy Options

Overview:

Many of the same point-of-sale policy options exist for e-cigarettes as for other tobacco products. However, policies must be written carefully to include definitions that encompass e-cigarettes so that they are not exempted from regulations around advertising, marketing, and warning labeling.[60] Important considerations are inclusion of e-cigarettes that do not contain nicotine, do not contain nicotine derived from tobacco, and definitions that are broad enough to include both current and future devices.[60] For an overview of policy options, review the Policy Playbook for E-Cigarettes co-created by the Public Health Law Center with Vaping Prevention Resource.

You can see what laws states across the U.S. have in place regarding e-cigarettes through the Public Health Law Center’s E-Cigarette Regulation: a 50 State Review or this Law Atlas map.

Youth Access

On December 20, 2019, federal legislation was signed into law raising the minimum legal sales age for tobacco products, including e-cigarettes from 18 to 21 nationwide. As with many policies, state action preceded federal action both with setting a minimum age for sale and in raising it to 21. In March 2010, New Jersey became the first state to ban the sale of e-cigarettes to minors and as of November 2021, 37 states and many communities have raised the minimum age of sale for e-cigarettes to 21, mirroring federal law. This allows state and local authorities to enforce the new minimum age and set additional restrictions.

Similar to strategies used to curtail youth access to conventional tobacco products, restrictions could include limiting self-service access of e-cigarettes or prohibiting the placement of e-cigarettes near candy/toys. Currently, federal legislation banning cigarette self-service displays does not apply to e-cigarettes. As of 2019, at least 14 states had banned self-service displays for e-cigarettes, and some cities and counties had as well. Review ChangeLab Solutions’ model self-service display ordinance for more information.

E-cigarette sales could also be restricted to adult-only retailers, which along with a comprehensive licensing policy, appropriately high licensing fee, and robust enforcement to ensure retailers are not selling to minors, could also help prevent youth access.[76]

Flavors

Another option for restricting the availability of e-cigarettes is to place restrictions on the sale of flavored products, which have strong youth appeal. The 2009 Tobacco Control Act banned flavored cigarettes, but other tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, can still be flavored. In response to rising levels of youth e-cigarette use, on September 11, 2019, the federal administration announced a future ban on the sale of flavored e-cigarettes, but final guidance from the FDA, issued January 2, 2020, only prohibits the sale of flavored cartridge-based (closed system) e-cigarette products other than menthol or tobacco flavor. With products like flavored disposable e-cigarettes left on the market, data from the Truth Initiative shows youth are switching from products like JUUL to products like Puff Bar and Smok. Between 2019 and 2020, the market share of disposable e-cigarette product like Puff Bar increased from 11% to nearly 25%, and as of 2021, Puff Bar had become the most popular e-cigarette product among youth.

It’s also clear that youth will use any flavor that is left on the market. As mint flavors in pod or cartridge-based e-cigarettes were prohibited, youth shifted to using menthol flavors, with the market share of menthol-flavored e-cigarettes increasing from 13% to 46% from 2019 to 2020.

The FDA has denied marketing authorization to millions of flavored e-cigarettes products through premarket view. While many public health groups are advocating for the agency not to authorize the marketing of any flavored e-cigarettes, it seems the agency is giving special consideration to menthol e-cigarettes, and in June 2024 authorized the sale of four menthol-flavored e-cigarette products. Some researchers advocate for leaving some limited flavors of e-cigarettes with only adult-oriented marketing on the market in order to increase the appeal of e-cigarettes to adults who want to quit smoking, while also limiting where and how e-cigarettes can be sold to further restrict youth access.[76]

In their press release about the authorization, the FDA noted, “…evidence submitted by the applicant showed that these menthol-flavored products provided a benefit for adults who smoke cigarettes relative to that of the applicant’s previously authorized tobacco-flavored products—in terms of complete switching—that is sufficient to outweigh the risks of the product, including youth appeal…” However, menthol-flavored e-cigarettes remain fairly popular among youth. According to the 2023 National Youth Tobacco Survey, 23.3% of high school students who use e-cigarettes use menthol flavors.

In November 2019, Massachusetts became the first state to prohibit the sale of flavored e-cigarettes along with all other flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes. Numerous localities around the country have restricted the sale of flavored e-cigarette products near schools and/or limiting their sale to adult-only establishments. In 2018, San Francisco became the first major metropolitan area to comprehensively prohibit the sale of all flavored tobacco product without exception within city limits. Other state action on the sale of flavored e-cigarettes includes:

- New Jersey, and Rhode Island have both banned the sale of all flavored e-cigarettes.

- New York has banned the sale of all flavored e-cigarettes except those that are approved through the FDA’s premarket review process.

- Maryland has banned the sale of all flavored cartridge-based and disposable e-cigarettes (except menthol flavor)

- Utah has restricted the sale of flavored e-cigarettes, other than mint and menthol, to tobacco specialty businesses.

There are also many local jurisdictions across the country that have enacted policies prohibiting or restricting the sale of flavored e-cigarettes, either as part of a more comprehensive policy restricting the sale of flavored tobacco products or as a separate ordinance focused on e-cigarette sales. See examples in the Public Health Law Center’s resource U.S. Sales Restrictions on Flavored Tobacco Products.

As with other types of flavor restrictions and bans, it’s important for restrictions on the sale of flavored e-cigarettes to be comprehensive. When the 2009 Tobacco Control Act prohibited the use of modified risk health descriptors such as “light,” “mild,’ or low tar in cigarettes, Marlboro circumvented the rule by changing the names of their “Marlboro Light” cigarettes to “Marlboro Gold,” while “Marlboro Ultra Lights” became “Marlboro Silver” and “Marlboro Mild” was renamed “Marlboro Blue”. [61] There’s also been a rise in ambiguous flavor names for cigarillos and little cigars (e.g. “blue”, “jazz”, “tropical twist”). Now e-cigarette companies will follow the same old Big Tobacco playbook and try to get around the restrictions any way they can, including by using vague “concept flavors” like “Solar” and “Marigold.” Some researchers have argued for specifically banning flavors with high toxicity as well as flavors with youth appeal.[62]

Learn more about restricting the sale of flavored e-cigarettes in the below:

- Restricting the Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products: Sample Language, Public Health Law Center

- Regulating Flavored Tobacco Products, Public Health Law Center

- Flavored E-Cigarettes Hook Kids, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids

Nicotine Concentration and Delivery

E-cigarettes contain varying nicotine concentrations that are delivered to the user at different rates. New 4th generation e-cigarettes like Juul and other pod mods contain high concentrations of nicotine – about 5% or 59mg/ml Most of them also use nicotine salts, which can deliver a higher concentration without as much throat irritation as would be the case with the freebase nicotine used in earlier e-cigarettes. Some brands have even higher nicotine concentrations. There are concerns that these high nicotine concentrations may lead to greater nicotine dependency. Canada, the UK, the EU all limit e-cigarette concentrations to 20 mg/ml.

The FDA could create a product standard for e-cigarettes that also limits both nicotine concentration and the level of nicotine salts. However, through the agency’s premarket review process, they have already authorized a product with a nicotine concentration of 4.8%.

Packaging

E-cigarettes also introduced a new health risk to children: the accidental ingestion of e-cigarette liquids. Between 2011 and 2014, poisoning cases related to e-cigarettes increased tenfold, with 3,638 e-cigarette-related calls to poison control centers in 2014. In response, the federal Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act, signed into law in January 2016, requires all liquid nicotine containers used for e-cigarettes and other vaping devices to be sold in child-resistant packaging. For more information, review the following resource: Public Health Law Center’s “Policy Approaches to Prevent Liquid Nicotine Poisonings”

Licensing

Many states and localities have begun incorporating vape shops and e-cigarette retailers into their tobacco retailer licensing (TRL) ordinances. As of June 2022, 37 states require licensing for over-the-counter sales of e-cigarettes. Licensing ensures that states and/or localities know where e-cigarettes are being sold and are better able to ensure the retailers selling them are following the law.

TRL can also serve as a tool to regulate the location, number, and types of retailers selling e-cigarettes. Setting a limit on the number of e-cigarette retailers located in an area may benefit public health. We know that when there are more tobacco retailers located in an area, people smoke at higher rates, youth are more likely to start smoking, and people who currently smoke have a harder time quitting. The same type of trends seems to be true for e-cigarette retailers. A 2014 study in New Jersey found that rates of both ever and past-month e-cigarette use were higher among students in schools located in an area with greater e-cigarette retail density.[63] Learn more about licensing and retailer density.

Licensing e-cigarette retailers can also help reduce e-cigarette use. In states that license e-cigarette retailers, the odds of adult e-cigarette use were significantly lower than in states without licensing.[64] A study assessing the impact of state e-cigarette regulations on prevalence of use found that when licensing was established, 18-24-year-olds were 6% less likely to initiate e-cigarette use.[65] In California localities that had a strong tobacco retailer license, a 2014 study showed that youth were 26% less likely to initiate e-cigarette use and 55% less likely have become a current e-cigarette user over the course of 1.5 years compared to localities that had no licensing law or did not have a licensing fee high enough to cover the costs of enforcement.[66] Another study found that in Pennsylvania, youth e-cigarette use dropped significantly following the implementation of licensing for e-cigarette retailers.[67]

Licensing is also key for enforcement. A California study assessing the impact of a statewide Tobacco 21 (T21) law on access to tobacco products and purchasing behaviors found that 82% of e-cigarette purchasers aged 18-20 reported that they were not refused sale in the past 30 days despite being underage.[68]

In April 2016, the Washington state legislature adopted rules to create a statewide licensing system for businesses that sell and distribute “vapor products,” including liquid nicotine. The state estimated that approximately 6,000 retailers would be affected by the new licensing rules, along with roughly 150 “vapor products” distributors. The rules, which took effect in fall 2016, require retailers to obtain a separate license to sell “vapor products” online.

In addition, many local communities have adopted their own licensing and permit requirements for e-cigarette retailers and vape shops. For example, San Marcos, California, passed an ordinance requiring any shop that sells tobacco products, including e-cigarettes and related devices, to purchase a city-issued “tobacco retail license.” The city partnered with the San Marcos Prevention Coalition and the Vista Community Clinic, which conducted surveys of local e-cigarette retailers and vape shops and determined that a number of businesses were selling these products to minors in violation of state law. San Marcos plans to use the tobacco license fees (roughly $190 per establishment) to ensure that businesses are complying with tobacco control regulations, including restrictions on selling to underage users. Read more.

Restrict Advertising, Particularly Towards Youth

Federal restrictions

The FDA has imposed some limited marketing restrictions on the e-cigarette products it has authorized through premarket review. However, many avenues that reach youth audiences remain open. As summarized by Eric Lindblom here, the marketing restrictions that the FDA has placed on Vuse Solo still allow promotion by social media influencers and celebrities, sponsorships (which are prohibited for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco), and advertising on TV and radio programs for which youth are no more that 15% of the audience.

The FDA has also placed a priority on enforcement against illegally marketed e-cigarette products that target youth, like Puff Bar, and has sent warning letters to companies marketing their products with cartoon characters or with packaging that imitates foods appealing to youth (e.g. Cinnamon Toast Cereal, Twinkies, Cherry Coke). However, these enforcement actions only reach the most egregious actors.

State and local restrictions

The Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act prohibits states and communities from regulating the marketing of cigarettes, but this law does not apply to other non-cigarette tobacco products like e-cigarettes. While this may be an option, advertising restrictions may face legal challenges related to commercial speech. Consult legal counsel and review the following resources from the Public Health Law Center for more information:

- Restricting Tobacco Advertising: Tips & Tools

- Regulating Tobacco Marketing: “Commercial Speech” Guidelines for State and Local Governments

- Regulating Tobacco Marketing: A “Commercial Speech” Factsheet for State and Local Governments

- Regulating Tobacco Marketing: A “Commercial Speech” Flowchart for State and Local Governments

Restrictions as a result of settlements

E-cigarette company Juul is facing several lawsuits based on their youth-centric marketing practices. A lawsuit from North Carolina Attorney General resulted in a $40 million settlement which also imposed some restrictions on the company’s marketing to youth, and one from the Arizona Attorney General resulted in a $14.5 million settlement, which will largely fund anti-addiction programs, but also creates an agreement that the company will not market or sell its products to young people, will implement strict age verification for online sales, and will monitor retailer compliance in the state. Another set of lawsuits resulted in a 33-state, $439 million settlement. While these settlements represent important steps in starting to reverse some of the harm Juul caused by marketing their addictive products to youth, trusting the company to monitor its own practices may not provide the most public health benefits, as noted in this commentary from the Public Health Law Center.

In addition, North Carolina’s Attorney General Josh Stein announced in November 2021 that he is suing the Juul founders for their personal roles in Juul’s marketing to youth, launching a statewide investigation into Puff Bar, retailers that sell flavored e-cigarettes, and e-cigarette distributors.

Learn more about the settlements and how these types of lawsuits could help address youth e-cigarette use in the Public Health Law Center’s resources:

- Roadmap to a National Settlement Agreement: How the Tobacco MSA Helps Frame a Juul Settlemen

- JUUL settlement tracker

- JUUL litigation FAQ

Learn more about the Juul settlements overall and their impact on the point of sale in our podcast episode on the topic:

Pricing

While research on the impacts of e-cigarette pricing is less extensive than on the impacts of cigarette pricing, the existing data show that both disposable and reusable e-cigarette sales are also responsive to price.[69] When e-cigarette prices increase, sales decrease, particularly among price-sensitive groups like youth.

While research on the impacts of e-cigarette pricing is less extensive than on the impacts of cigarette pricing, the existing data show that both disposable and reusable e-cigarette sales are also responsive to price.[69] When e-cigarette prices increase, sales decrease, particularly among price-sensitive groups like youth.

A study using sales data from California from 2012-2017 found that when prices of reusable e-cigarettes increase, sales of disposable e-cigarettes increase. While cigarette demand was not responsive to changes in e-cigarettes prices, when cigarette prices increase, sales of reusable e-cigarettes increased. [70] This indicates that as cigarette prices increase, people may substitute reusable e-cigarettes, and as prices for reusable e-cigarettes increase, people may substitute disposable e-cigarettes.

E-cigarette companies are engaging in a number of tactics to reduce the price of e-cigarettes to consumers. Data from the most recent FTC E-Cigarette Report, issued in April 2024, shows that in 2021, e-cigarette companies spent:

- $261.6 million on price discounts, which includes payments to retailers and wholesalers to reduce the price of e-cigarettes to consumers.

- $59.5 million on sampling and distribution of free and deeply discounted e-cigarette products

- $27.4 million on coupons.

The strategies listed below can raise the price of e-cigarettes and counter the industry’s price-reduction tactics to keep them high:

Taxation

E-cigarettes are not taxed as tobacco products at the federal level, which makes the disposable and less advanced e-cigarettes often cheaper than conventional cigarettes. However, 30 states have taken initiative to create policies at the state level as of June 2022. At the forefront of the issue, several questions arise on whether the tax should apply to e-liquid solutions, devices, cartridges, and/or component parts and accessories; be applied at the retail or wholesale level; at the state or local level; and what type of tax (e.g. specific, ad volorem, or a combination) is most effective. Some, including California, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania, and D.C. tax e-cigarettes on a percentage of the wholesale price in order to apply across a wide variety of products and sizes, while others, including Delaware, North Carolina, Kansas, Louisiana, and West Virginia tax per milliliter of nicotine liquid. Some local governments have also implemented taxes on e-cigarette products. For example, Chicago taxes by unit and volume: $0.80 per product unit, plus an additional $0.55 per mL liquid.

Some researchers argue that e-cigarettes should be taxed at a rate that creates a price high enough to discourage youth initiation, but at a rate that is also lower than the tax on cigarettes, proportional to the products’ lower level of danger. [71,76] However, many states also have cigarette taxes that have not been raised in a decade or more and at least a dozen still have taxes that are less than $1.

Review the Public Health Law Center’s resource Taxing E-Cigarette Products for more information.

Price Promotions

The tobacco industry also uses prices, promotions, and coupons to make e-cigarettes cheaper to the consumer. In 2015, 20.2% of tobacco retailers across the country offered price promotions on e-cigarettes, and these promotions were more prevalent in neighborhoods with more residents who are Hispanic. [72] States and communities may consider restricting or prohibiting coupon redemption and other price promotions such as buy-one-get-one-free offers. Several localities and three states (New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island) have prohibited the redemption of coupons and price discounts on tobacco products, including e-cigarettes. This helps to keep prices high and acts as a complement to excise taxes.

Learn more about point-of-sale pricing policies for all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.

Additional Resources

For general information on e-cigarette and nicotine-delivery device patterns of use, health effects, marketing, and policy implications, review:

- CDC’s webpage on E-cigarettes

- CDC Infographic: Electronic cigarettes: What’s the bottom line?

- On historical trends:

- Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes, a report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine

- Truth Initiative’s E-cigarettes: Facts, stats, and regulations

- Public Health Law Center’s collection of resources on e-cigarettes