Health Equity and Point of Sale Tobacco Control Policy

Significant progress in tobacco control and prevention has contributed to impressive declines in commercial tobacco use and smoking across adult and youth populations. The US has steadily expanded tobacco protections since 1964 – with less smoke in the air and fewer advertisements for harmful products as a result. In 2021, smoking rates decreased to 11.5% of adults across the US, the lowest prevalence ever.[1] However, as the prevalence of smoking declines overall, not all populations are equally protected, and as a result, certain subpopulations bear a burden of higher disease and death outcomes as a result of tobacco use and exposure to smoking. Certain racial and ethnic communities, low-income communities, and LGBTQ communities are exposed to more point-of-sale (POS) advertising, live in places with a higher concentration of retailers that sell tobacco products, and have a higher prevalence of smoking. Tobacco industry documents reveal that disparities in the retail environment are no coincidence; in fact, the tobacco industry strategically markets their deadly products in communities with limited resources, lower income, and less education.[2, 3] Regulating what, where, how, and for how much tobacco products are sold at stores can help counter the malicious marketing tactics of the tobacco industry. As retail tobacco policies continue to develop, policy makers and practitioners should consider how the implementation of these policies may improve equity, maintain current disparities, or exacerbate pervasive health inequities. This page highlights some policy examples or ways of structuring retail tobacco policies to improve health equity. Click on the following sections to scroll down:

- What is Health Equity?

- Challenges to Achieving Health Equity

- Evidence for Pro-Health Equity Solutions

- Health Equity Impact Assessments

- Prioritizing Menthol and Flavored Tobacco Bans to Improve Health Equity

- Increasing the Price of Tobacco & Increasing Access to Cessation Services

- Retailer Density Caps and Proximity Restrictions to Address Disparities

- Health Equity in Implementation and Enforcement

- Conclusions

See two key resources on this topic below:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Office on Smoking and Health has published a new supplement to the Best Practices User Guides, Tobacco Where You Live: Retail Strategies to Promote Health Equity. The document was written in partnership with the Center for Public Health Systems Science at Washington University in St. Louis. Tobacco retailers are concentrated in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. Retail strategies can advance health equity by limiting access to and availability of commercial tobacco products, reducing exposure to tobacco marketing, and promoting cessation. The Tobacco Where You Live: Retail Strategies to Promote Health Equity supplement can help you:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Office on Smoking and Health has published a new supplement to the Best Practices User Guides, Tobacco Where You Live: Retail Strategies to Promote Health Equity. The document was written in partnership with the Center for Public Health Systems Science at Washington University in St. Louis. Tobacco retailers are concentrated in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. Retail strategies can advance health equity by limiting access to and availability of commercial tobacco products, reducing exposure to tobacco marketing, and promoting cessation. The Tobacco Where You Live: Retail Strategies to Promote Health Equity supplement can help you:

- Understand the local retail environment

- Implement commercial tobacco retail strategies equitably

- Learn how communities have used retail strategies to advance health equity

- Identify the best resources and tools to get started.

What is Health Equity?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, health equity means that everyone has the opportunity to achieve their greatest level of health, despite social, economic, or environmental factors. In developing a policy, it is important to identify which members of the population will be impacted by a policy option and how the policy will address social and environmental characteristics that contribute to differential health outcomes, often referred to as social determinants of health. Social determinants of health include factors such as access to health care, education, and economic stability. For more on health equity, see these resources from Policy Link.

In the context of tobacco control, it is well documented that low-income, less educated, and historically disadvantaged groups have a higher burden of tobacco use and poorer tobacco-related health outcomes. A health equity policy approach critically assesses the equal or unequal distribution of a policy’s impacts across groups with distinct, socially determined characteristics that contribute to tobacco use and avoidable health disparities.

Challenges to Achieving Health Equity

Some challenges to understanding how policy can effectively address the social determinants of health include: (1) the complexity of the context, including how to address multiple or overlapping determinants across diverse and uniquely situated groups; (2) the length of time needed to demonstrate impact; (3) the difficulty in navigating interorganizational and intersectoral partnerships; and (4) competing priorities of less complexity.[4]

To mitigate these challenges, practitioners and policymakers must make concerted efforts to authentically understand the contextual issues to inform policy making. Significant considerations in tobacco point-of-sale policy include:[5, 6]

- Smoking prevalence: Is tobacco at the POS experienced differently by community members of particular socio-demographics, such as age, race, heritage, income, level of education, employment type, gender, sexual identity, geography, and/or neighborhood characteristics?

- What smoking attributable health issues are identified in the community?

- Is there up-to-date data on policies related to tobacco at the POS including information on legislative progress in tobacco control and state preemption? Data sources can include a list of applicable policies, evaluative data on policy effectiveness, tobacco control bill voting history by political representatives, etc.

- What is the level of tobacco awareness and education in the community? Is there existing support in the form of tobacco coalitions, state allocation to tobacco control and prevention, and strong community knowledge on the risks associated with smoking?

To learn more, review the CDC’s Best Practices Guide to Health Equity in Tobacco Control and Prevention.

Evidence for Pro-Health Equity Solutions

The evidence base for the health equity impact of tobacco control policies at the POS is growing. Local and state-level practitioners are recognizing the importance of health equity impact assessments and equity-framed monitoring and evaluation to measure progress in improving equity outcomes. Several case studies document the implementation of tobacco interventions at the POS, but many of the evaluations are in-progress and the pro-equity effects of POS policy may take time to occur.

Health Equity Impact Assessments

A process to formally and systematically analyze the health effects of a point-of-sale policy can include conducting a Health Equity Impact Assessment.

As described in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s guide, “Community Tools to Promote Equity Guide”:

The assessment process uses data and local stakeholder input to understand the often overlooked benefits and consequences of a given proposal. The Health Equity Impact Assessment relies on the premise that most policy and programs will inevitably affect population health in some way and that it is better to understand those outcomes before final decisions are made. Recommendations to change a proposal based on Health Equity Impact Assessment results can help improve health equity and outcomes.

A principal purpose of a Health Equity Impact Assessment is to help policy practitioners gauge how a policy will affect those community members at greatest risk for tobacco use, especially those community members historically targeted and adversely impacted by Big Tobacco.

Example of A Health Equity Impact Assessment to Inform Point-of-Sale Tobacco Policy

In 2015, Multnomah County in Oregon conducted a Health Equity Impact Assessment to consider how a Tobacco Retail Licensing (TRL) policy would contribute to health equity within their community. TRL policies, which require businesses to obtain a license to sell tobacco products, can help reduce illegal sales to minors and can also be used as a regulatory platform to enforce other point-of-sale policies. However, leaders in Multnomah County understood that their policy plan would need to be tailored to the specific needs of their community. By prioritizing feedback and input from stakeholders in Multnomah County, including both youth and retailers, gathered during the Health Equity Impact Assessment, they adapted their policy adoption and implementation plans to balance the effect of the policy on various stakeholders and mitigate any unintended outcomes that may have worsened community progress in health equity.

In 2015, Multnomah County in Oregon conducted a Health Equity Impact Assessment to consider how a Tobacco Retail Licensing (TRL) policy would contribute to health equity within their community. TRL policies, which require businesses to obtain a license to sell tobacco products, can help reduce illegal sales to minors and can also be used as a regulatory platform to enforce other point-of-sale policies. However, leaders in Multnomah County understood that their policy plan would need to be tailored to the specific needs of their community. By prioritizing feedback and input from stakeholders in Multnomah County, including both youth and retailers, gathered during the Health Equity Impact Assessment, they adapted their policy adoption and implementation plans to balance the effect of the policy on various stakeholders and mitigate any unintended outcomes that may have worsened community progress in health equity.

The Health Equity Impact Assessment in Multnomah County analyzed the potential impacts of a TRL policy that prohibited retailers within 1000 feet of schools; limited mobile retailers; and limited price promotions, coupons, and free samples, as these were the provisions included in a statewide licensing bill that was introduced in the Oregon State Senate in 2015 but did not pass, in part due to disagreement over the provisions included.

Consistent with existing data from other community contexts demonstrating how enacting a TRL policy helps to curb youth access to tobacco products,[7] the assessment suggested that a TRL policy could reduce sales to youth and youth of color in Multnomah County, which could, in turn, lead to less youth experimentation with tobacco, which could result in health care cost savings. However, in order to fully protect youth, the Heath Equity Impact Assessment work-group recommended ensuring that the licensing system include sustainable funding for enforcement (e.g. through a licensing fee that is high enough to cover costs for retailer education and inspections) and the ability to suspend or revoke licenses.

The Multnomah County Health Equity Impact Assessment also took seriously the needs and concerns of stakeholder groups, such as people who currently smoke and tobacco retailers, and assessed in particular the effect the policy would have on economic vitality. For example, their recommendations included making sure retailer trainings were culturally and linguistically accessible, supporting small business owners who decided to stop selling tobacco, ensuring the policy would be equitably enforced, and increasing funding for culturally responsive smoking cessation programs.

As a result of the Health Equity Impact Assessment as a formative input to accurately capture the extent of the problem and engage collaboratively with the community, the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners unanimously adopted a tobacco retailer licensing ordinance in 2015. The ordinance requires tobacco retailers to obtain licensure and to comply with all applicable laws in order to sell addictive tobacco products like cigarettes, cigars, chew, and e-cigarettes. To follow through on the equity promise in implementing the retailer license ordinance, the county established an advisory board to include retailers, youth, residents, and public health practitioners. Additionally, ordinance implementation focused on retailer education, including disseminating ordinance materials in different languages and including the community in retailer outreach and compliance checks. Learn more about Multnomah County’s TRL policy development and implementation process. Future evaluation may give insight to the equity impact of the retailer licensing ordinance for youth of color, LGBT youth, and low-income residents.

Read the full Health Equity Impact Assessment here: Multnomah County Tobacco Retail Licensing Policy: A Health Equity Impact Assessment (Upstream Public Health, 2015)

State and local governments can conduct a health equity impact assessment for any policy. For example, in June 2017, Multnomah County also conducted a health equity impact assessment for a Tobacco 21 policy.

Prioritizing Menthol and Flavored Tobacco Bans to Improve Health Equity

Despite a ban on characterizing flavors other than menthol in cigarettes in the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, menthol cigarettes and other dangerous non-cigarette flavored tobacco products are still available and heavily marketed to youth, African Americans, and other disadvantaged groups. As a result of the flavored tobacco product availability and targeted marketing, there are distinct patterns among people who use tobacco with youth, African American, and other historically disadvantaged groups using flavored products, especially menthol, at higher rates. While states and localities have begun to enact policies that prohibit the sale of a wider range of flavored tobacco products, some including menthol cigarettes, as of December 2018 those policies covered only 6.3% of the US population; and youth, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islander remain less protected by these policies than other vulnerable groups.[33] Learn more about flavored tobacco products here.

Banning or restricting the sale of flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes, has a significant potential to improve health equity. A report from the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee shows that if menthol cigarettes were banned, 39% of all people who smoke menthol cigarettes and 47% of African Americans who smoke menthol cigarettes would quit.[8] A menthol ban could also curb both initiation and progression to regular smoking among youth, as 80% of youth who have ever tried tobacco started with a flavored product,[9] and youth who initiate smoking with menthol cigarettes are 80% more likely to later smoke every day.[10]

Example: Chicago, Illinois

Chicago, Illinois became the first city to limit the sale of flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes, within 500 feet of schools. The policy was passed in December 2013 with an effective date in July 2014, and was fully implemented in July 2016. [11] Read the Public Health Law Center’s Chicago’s Regulation of Menthol Flavored Tobacco Products: A Case Study, examining the groundwork, implementation, and lessons learned from the policy.

Chicago, Illinois became the first city to limit the sale of flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes, within 500 feet of schools. The policy was passed in December 2013 with an effective date in July 2014, and was fully implemented in July 2016. [11] Read the Public Health Law Center’s Chicago’s Regulation of Menthol Flavored Tobacco Products: A Case Study, examining the groundwork, implementation, and lessons learned from the policy.

Health equity played a key role in driving the policy forward. Much of the success was driven by a community call to action facilitated by the Chicago Board of Health to find solutions to curb youth tobacco use. The Board of Health collaborated with Chicago residents and health supporters at town halls to gather community input for flavor restrictions at the POS. Recognizing the disproportionate impact of flavored tobacco, and especially menthol, among groups including LGBTQ youth and racial and ethnic minority individuals who smoke, the town halls were conducted in neighborhoods with members most affected by tobacco and menthol use.

Using social justice as a frame for the issue, the community helped make the case for the policy by highlighting the tobacco industry’s aggressive tactics to market flavored products to youth, especially those in minority communities. Policy advocates helped to raise awareness around the prevalence of menthol and flavored products in the community by engaging diverse stakeholders, including tobacco coalitions, national health organizations, and non-traditional partners who were previously unaware of the issue.

The collective and collaborative approach led to an instrumental win to improve health equity at the POS. As a result, other communities have been able to pass similar and increasingly comprehensive policies. Since implementation of the flavor ban in Chicago in 2014, several localities in California, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and Minnesota have taken a stand against Big Tobacco to achieve health equity with additional restrictions on the sale of flavored tobacco products. Some local jurisdictions in Massachusetts and Minnesota had initially only restricted the sale of flavored tobacco not including menthol, but have since updated their tobacco ordinances to include menthol cigarettes.

Example: San Francisco, CA

Building off Chicago’s success and many years of groundwork, the city of San Francisco took action to become the first major metropolitan area to completely ban the sale of menthol cigarettes and all other flavored tobacco products in June 2017.

San Francisco policymakers and many residents felt the ordinance was necessary due to the clearly documented impacts of flavored (including menthol) tobacco products on youth initiation to tobacco use and the well documented disparities in menthol tobacco use for LGBTQ, Black, and Asian/Pacific Islander (API) populations due to the tobacco industry’s targeted marketing. The history of marginalized communities in San Francisco being targeted by the industry is often exemplified by the tobacco industry’s Project SCUM (Sub Culture Urban Marketing). Project SCUM focused on targeting San Francisco’s LGBTQ and homeless populations thought tobacco advertisement content and location. Being able to specifically name San Francisco communities as victims for targeted advertising was a strength of the campaign to pass the ordinance. This targeting of particular communities is an issue across the US, with well documented impacts of higher smoking rates within the targeted communities. You can read more about disparities in tobacco advertising here.

Essential to San Francisco’s strategy was the focus on raising awareness of the social justice aspects of the flavors and menthol use in their community. The coalition that pushed the policy forward, including the San Francisco Department of Health, Breathe California, African-American Tobacco Control Leadership Council (AATCLC), California LGBTQ Tobacco Partnership, and University of San Francisco’s cancer program, united around their shared interest in health disparities and collectively decided to focus funds and time on engaging the community around the issue of menthol.

The coalition’s first move was to engage the community with education around the dangers of menthol tobacco products with the intention of gaining letters of support. They reached out to local community based organizations (CBO), and offered information, data, and talking points for direct service providers to share with their participants. The coalition also continued to hold meetings within Black and API communities to discuss the harms of menthol products, targeted advertising within these communities and what should be done. They later expanded these meetings to more impacted communities, with the goal of a well-informed community backing the policy when voting (see more below).

The coalition’s first move was to engage the community with education around the dangers of menthol tobacco products with the intention of gaining letters of support. They reached out to local community based organizations (CBO), and offered information, data, and talking points for direct service providers to share with their participants. The coalition also continued to hold meetings within Black and API communities to discuss the harms of menthol products, targeted advertising within these communities and what should be done. They later expanded these meetings to more impacted communities, with the goal of a well-informed community backing the policy when voting (see more below).

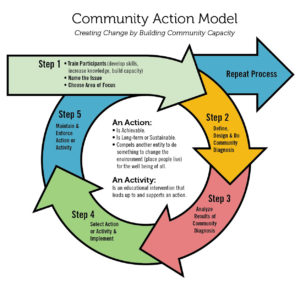

Using the Community Action Model (CAM), the coalition continues to work with youth programs in Bay View, the Tenderloin, and the Mission (historically Black, Latino, and API neighborhoods within the city) to further engage the community through surveys, assessments, data analysis, and talking points. This engagement began before the passing of the ordinance and continues as a means of supporting youth and community education on tobacco. Breathe CA began working with youth by engaging youth-focused CBOs. They talked with youth about the ease of access to tobacco products, product use, and flavors, and offered infographics. Breathe CA also has a media campaign and regularly works to engage the larger local community. Framing the campaign outreach messaging as a social justice issue and as avoidable has helped build community support over time.

When deciding how to write the ordinance, the coalition and supporting policymakers made several decisions based on lessons learned from Chicago’s menthol restriction policy, which was partially rolled back after the city passed a Tobacco 21 policy and left the buffer zone only around high schools, not grade schools. The key to success, San Francisco decided, would be simplicity. The language of the San Francisco’s policy is straightforward with no exceptions. While tobacco retailers are the face of the opposition to the ordinance, stakeholders engaged in policymaking that impacts such retailers have noted that small, local retailers prefer that the policies impacting their stores be simple, fair, and consistent, and not based upon locations or buffer zones, which are perceived as benefiting some stores over others. Concise policy language is also often more legally defensible and easier to message; as well, this language would ideally prevent some of the complications around framing and buffer zones that occurred with Chicago’s model policy.

The San Francisco City Council and Health Committees unanimously passed the menthol restriction ordinance in June 2017, and it was approved by Mayor Ed Lee. Implementation was originally set for January 1, 2018, but was pushed back to April 2018 as a consideration for store owners who would need time to transition and as a way to give the city time to consider ways to assist retailers through programs like Healthy Retail SF. The tobacco industry very quickly moved to stop implementation by collecting signatures, ultimately paying $5 per signature for over 5,000 signatures to force the ordinance restricting the sale of their deadly products into referendum. Despite R.J. Reynolds spending nearly $12 million on campaigns against the ordinance, the established coalition continued to engage the community and work towards a positive outcome for the San Francisco menthol restriction ordinance. On June 5, 2018, San Francisco residents voted 68% to 31% to uphold the policy. Learn more here.

Increasing the Price of Tobacco & Increasing Access to Cessation Services

People living below the U.S. poverty line, people facing underemployment, and people with lower educational attainment have higher use of cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco. Some contributing factors to this disparity include a higher density of tobacco retailers in lower-income neighborhoods, less access to healthcare, increased exposure to secondhand smoke, and less successful quit attempts. The tobacco industry has also targeted their marketing to and offered deeper discounts in low-income neighborhoods.[12] Policy options aimed at improving health equity should consider how a policy could curtail the difference in outcomes between lower income and higher income groups.

One policy option includes increasing the price of tobacco products. Raising tobacco prices, whether through taxes, banning the redemption of coupons and other discounts, and/or setting minimum floor prices, is one of the most effective strategies for reducing initiation, decreasing consumption, and increasing cessation. [13] It is also a strategy that can reduce tobacco use among low-income groups and reduce socioeconomic disparities in smoking; in fact, one study found that increasing tobacco prices was the only policy option of those assessed to show a significant pro-equity effect.[14]

Research has found that raising the prices of tobacco products directly benefits youth and low-income groups by making tobacco products less accessible for these price-sensitive groups. [15, 16] The sensitivity of low-income communities to tobacco price increases prompts more quit attempts or reductions in tobacco use. [17] While any price increase may reduce use, eliminating low-price tiers of cigarettes or other tobacco products through a minimum floor price could help reduce socioeconomic disparities in smoking because lower income people who smoke are more likely to buy discount brands and models show these type of policies produce the greatest reductions in consumption among low-income populations.[18, 19]

In order to maximize effectiveness of these policies, jurisdictions should consider raising the prices of all tobacco products, not just cigarettes, to ensure that low price tobacco alternatives are also equally inaccessible to tobacco consumers who might try or switch to other tobacco products if they were cheaper. [20, 21]

Minimum floor price laws can also help reduce the ability of the tobacco industry to target African American neighborhoods or other geographic areas with deeper discounts on menthol cigarettes or little cigars and cigarillos, helping to reduce the disparate marketing and price promotions that these communities are often subjected to. [22, 23]

However, raising tobacco prices is not enough to achieve health equity outcomes. Policymakers should also consider pairing these policies with funds for education and awareness initiatives to promote the internalization of smoking harms among low-incomes groups who may not immediately see the policy benefit.[24] Finally, in order to maximize the benefits and minimize harm, policies should include ways to support cessation amongst the populations who are most affected, by, for example, providing funds to implement for free and low-cost quit services and cessation support for people who smoke and are motivated to quit as a result of the policy and to counteract negative financial impacts for low-income people who smoke and are not ready to quit.

Learn more about increasing prices through non-tax approaches here.

Example: New York, New York

The state of New York has notable tobacco policies that stand out above other states in the country, including having the second-highest tax on cigarettes at $4.35 per pack. However local policy in New York City moved beyond the state-level legislation to increase tobacco pricing through the Sensible Tobacco Enforcement Policies enacted in 2013 and updated in 2017, which requires that cigarettes and little cigars be sold for at least $10.50 per pack starting in 2013 and for $13 per pack starting in 2017. To circumvent consumption of cheaply priced tobacco alternatives, the policy also stipulated that little cigars must be sold in packs of 20 and cigars that are sold individually and cost less than $3 must be sold in packs of four or more. The policy also prohibited tobacco retailers in New York City from redeeming tobacco coupons or other tobacco price discounts. The city later adjusted the policy to include a minimum price for 4-packs of cigars ($8, plus $2 for every additional cigars) to prevent the tobacco industry from selling 4- and 5-packs for less than $1, and at the same time, set minimum prices for smokeless tobacco and hookah as well. Learn more in this case study: Reducing Cheap Tobacco & Youth Access: New York City.

The state of New York has notable tobacco policies that stand out above other states in the country, including having the second-highest tax on cigarettes at $4.35 per pack. However local policy in New York City moved beyond the state-level legislation to increase tobacco pricing through the Sensible Tobacco Enforcement Policies enacted in 2013 and updated in 2017, which requires that cigarettes and little cigars be sold for at least $10.50 per pack starting in 2013 and for $13 per pack starting in 2017. To circumvent consumption of cheaply priced tobacco alternatives, the policy also stipulated that little cigars must be sold in packs of 20 and cigars that are sold individually and cost less than $3 must be sold in packs of four or more. The policy also prohibited tobacco retailers in New York City from redeeming tobacco coupons or other tobacco price discounts. The city later adjusted the policy to include a minimum price for 4-packs of cigars ($8, plus $2 for every additional cigars) to prevent the tobacco industry from selling 4- and 5-packs for less than $1, and at the same time, set minimum prices for smokeless tobacco and hookah as well. Learn more in this case study: Reducing Cheap Tobacco & Youth Access: New York City.

New York City’s Sensible Tobacco Enforcement Policy decisions have direct implications in closing the gap on health disparities shaped by a tobacco consumers’ economic status. To strengthen these outcomes, New York City and other localities considering this policy option could increase spending on state tobacco control efforts more broadly. For example, in 2019, the state of New York received an estimated $2 billion in revenue from tobacco settlement payments and taxes, but less than 20% of these funds were allocated to state spending on tobacco control. Allocating additional funds to bolster cessation treatment options for low-income communities, facilitate access to better care, and take action to reduce tobacco advertising and marketing in low income neighborhoods could enhance the equity impacts of these type of policy solutions grounded in addressing determinants of tobacco use.

Additional case study: Regulating Price Discounting in Providence, RI – Case Study

Resources:

- ChangeLab Solutions’ Factsheet: Minimum Floor Price Laws

Retailer Density Caps and Proximity Restrictions to Address Disparities

The number of tobacco retail stores in a community is linked to increased smoking rates, increased smoking-related death and disease outcomes, and the normalization of tobacco use in a community. Finding ways to reduce the presence of retail outlets in a community could help curtail tobacco use. Taking actions to reduce the number of tobacco retailers is especially important for low-income communities and neighborhoods with more people of color, where research has found an overconcentration of tobacco retail outlets.[25] Retailers such as these not only sell tobacco products but provide readily available space for Big Tobacco to place their ads and expose community members to targeted tobacco marketing.

To limit the number of tobacco retail outlets, one policy option is a retailer licensing ordinance that includes caps on the number of retailers in each neighborhood or city and places limits on where tobacco retailers can be located. Using mapping tools, communities can examine data on tobacco retailer locations and overlay this information with important demographic variables using census data, as well as the locations of schools and other youth-oriented venues. Mapping can help build a case for reducing the number of retail outlets, especially if the data shows inequities in the distribution of tobacco retailers across neighborhoods.

A study conducted in Missouri and the State of New York found that if tobacco sales were prohibited within 1000 feet of schools, it would not only reduce tobacco retailer density across the board, but would nearly eliminate existing race- and income-based disparities in density between neighborhoods.[9]

Example: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

In 2016, following an example set by San Francisco in 2014, the City of Philadelphia passed a regulation to reduce the number of tobacco retailers near schools and to address disparities across neighborhoods. At the time, per capita tobacco retailer density in low-income areas of the city was 69% higher than in high-income areas. The city’s new regulatory standards limited the number of tobacco retailer permits to one permit per 1000 people in each planning district. In addition, to remedy disparities in the number of stores near schools (low-income areas in the city had 63% more retailers located within 500 feet of schools than high-income areas), no new permits were to be issued to retailers for locations within 500 feet of K-12 schools. Any existing retailers within the 500 feet limit could retain their permit only if they complied with rules to prevent tobacco sales to minors, but could have their permit revoked for too many violations. The ordinance also standardized and strengthened penalties for retailer violations to reduce repeated violations from the same stores.

Prior to implementation, the Get Healthy Philly team used geographic information mapping systems to illustrate the proximity of retailers to schools in low-income areas. The team also worked to make certain that retailers impacted by the policy plan could provide input and voice concerns during the policy development phase.

By 2019, three years after the policy went into effect, the density of tobacco retailers in the city declined by over 20%, with a greater decrease in low-income districts, and the rate of retailers within 500ft of schools declined by 12%.[34] Future evaluation data is expected to demonstrate the policy’s impact on important health equity indicators such as tobacco use and dependence within low-income communities and communities of color, perceived exposure to tobacco products, and distance of tobacco outlets from residents’ home and work environments.

Learn more about the policy in our Story from the Field: Reducing Retailer Density in Philadelphia

Example: San Francisco, California

San Francisco’s Tobacco Use Reduction Act aims to halve the number of tobacco retailers in the city over the course of 10-15 years by creating a cap of 45 tobacco sales permits in each of the 11 city districts. This cap aims to reduce disparities in retailer density in lower income and minority communities. The policy also prohibits any new retailers from locating within 500 ft of either a school or another retailer. For more details on the city’s strategy and lessons learned, review Reducing Tobacco Retail Density in San Francisco: A Case Study. Watch this video from the youth of San Francisco’s Tobacco Use Reduction Force (TURF) to learn more about the law and why it is so important.

Mapping the Retail Environment to Assess the Health Equity Impact

It is important to consider all potential implications of POS policy options, including the unintended consequences, to determine if it will reduce, maintain, or exacerbate health disparities. Using mapping tools to model a potential policy’s resulting retailer reduction alongside demographic data across and within communities can reveal the impacts of a given policy on current disparities in retailer density.

Example: Tobacco-Free Pharmacies in New York City

In 2014, CVS became the first national retail pharmacy to abandon the sale of tobacco in their stores. Following the chain’s action, total cigarette purchases in states where CVS holds significant market share declined by 1%, and people who had previously purchased their cigarettes exclusively at CVS were up to twice as likely to stop buying cigarettes entirely.[26]

Local governments across California, Massachusetts, New York, and Minnesota have implemented policies prohibiting any pharmacy from selling tobacco, and in 2018, Massachusetts became the first state to enact the policy. This type of policy is a way to reduce overall retailer density. Learn more here.

However, communities considering this as a policy option should be aware of where pharmacies that sell tobacco products are located in relation to high-risk smoking groups. Not all policies that decrease tobacco use at a population level also reduce disparities in tobacco use. For example, as a standalone policy, prohibiting tobacco sales in pharmacies may not reduce inequities in a community with more corner stores and liquor stores than pharmacies.

A study evaluating the impact of a tobacco-free pharmacy law in New York City found that higher-income, white neighborhoods benefited from the policy option more so than low-income neighborhoods, because fewer pharmacies are located in low-income neighborhoods.[27] Low-income neighborhoods in NYC traditionally have other retail settings that sell tobacco that are not pharmacies, including corner stores and convenience stores called ‘bodegas’, which are visited more frequently by minority and low-income groups.[27] As noted, NYC has not implemented this policy alone – it is only one piece of their efforts to reduce tobacco use across the city.

Discernment for the unique attributes of the retail environment and policy context is key to achieving health equity. Conducting a community health assessment or health equity impact assessment before implementing a tobacco-free pharmacy policy or any point-of-sale policy is a meaningful approach to identifying if a policy option has the potential to equitably benefit community members.

Health Equity in Implementation and Enforcement

Another key consideration in the health equity impacts of any given point-of-sale policy is ensuring that it is enforced equitably.

For example, the youth access laws in many states and cities include penalties for the underage purchase, use, and possession (PUP) of tobacco products. However, the evidence of the effectiveness of PUP provisions in reducing youth tobacco use is limited, particularly among those at higher risk for smoking; as well, these type of laws may have adverse consequences for youth who are already addicted, divert police resources, and be inequitably enforced against young people of color. [28, 29 ] Model Tobacco 21 policies recommend replacing PUP laws and any associated criminal penalties with a civil penalty structure. Learn more about PUP laws in the following resources:

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’ Youth Purchase, Use, or Possession Laws are Not Effective Tobacco Prevention

- ChangeLab Solutions’ PUP in smoke: Why Youth Tobacco Possession and Use Penalties are Ineffective and Inequitable

Instead of focusing on youth who have been the victims of targeted advertising, youth access laws can place the responsibility on retailers to not sell to anyone underage. To ensure that retailers are complying with the law, federal, state, and local agencies can conduct compliance checks that include undercover buys with youth decoys. The funding for this type of enforcement should be sufficient so that all retailers are visited at least once per year and that those retailers that violate the law have at least one follow-up visit by the enforcement agency. However, research also shows that neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black, Latino, and young residents are more likely to have higher rates of underage sales.[30] Oversampling for inspection in these areas, for instance by using stratified, cluster sampling at the zip-code or census-tract level, may help ensure retailer compliance and reduce this disparity. [31,32]

Another consideration in equitable policy implementation and enforcement is ensuring that the policy language applies only to commercial tobacco, not to ceremonial tobacco used by Native Americans, as noted in Multnomah County, OR’s health equity impact assessment of a Tobacco 21 policy.

For key principles to follow in designing an equitable enforcement system, see Decriminalizing Commercial Tobacco: Addressing Systemic Racism in the Enforcement of Commercial Tobacco Control. To learn more, view the Equitable Enforcement in Commercial Tobacco Control webinar recording below:

Conclusions

Point-of-sale tobacco policies have the potential to improve health equity when the policy planning process includes conducting formative research to understand the community and policy context, such as through a Health Equity Impact Assessment.

Some health departments and associations, such as the Massachusetts Public Health Association, have chosen to design their own Health Equity Policy Framework to ensure that health equity is a guiding principle in all aspects of their work.

Recognizing which policy options have immediate benefits to high risk tobacco groups can push the needle forward toward health equity. Mapping the retail environment to fully understand the tobacco landscape in a community can help to avoid inequitable consequences or uneven benefit across community groups.

For more information, also see ChangeLab Solution’s Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Inequities: Resources to Inform Point-of-Sale Policies.

It is important to remember that for policy efforts to effectively improve health equity, comprehensive policy approaches that address tobacco use from multiple angles are needed to help maximize benefits and minimize harm (e.g. raising the price of tobacco products while also allocating funds to support cessation services in low-income communities).

While many point-of-sale policies hold great promise to reduce current inequities in tobacco retailer density, point-of-sale tobacco marketing, and ultimately tobacco-related death and disease, evaluation of the impacts of these policies post-implementation will be critical to ensuring their more widespread adoption.