1. A Focus on Health Equity in Point-of-Sale (POS) Tobacco Control

As recent data from the CDC shows, while smoking rates are down to 15.5% among the general U.S. adult population, rates are much higher among those with lower levels of income and education, among American Indian/Alaska Natives, among men, among LGBTQ individuals, among those with mental illness, those with disabilities, those who are uninsured or on Medicaid, and those living in the South and Midwest.

CounterTobacco.org predicted a focus on health equity in 2017 as well, and it continues to be relevant. In 2017, San Francisco successfully used a social justice frame to pass their policy prohibiting the sale of menthol and any other flavored tobacco products within the city. In 2018, as awareness of the disparities in tobacco use rates grow, expect to see more about how the tobacco industry’s targeted advertising campaigns (e.g. focusing on the military, those with mental illness, on the “menthol wars” in African-American neighborhoods, on LGBTQ+ populations, etc.) have contributed to these inequities, and how point-of-sale (POS) policies can help eliminate the disparities we see in tobacco retailer density and POS advertising.

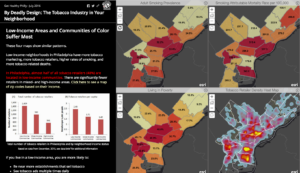

We now know more about what works to help eliminate some of the disparities in retailer density, which contribute to disparities in tobacco use. Research conducted in New York and Missouri has shown that bans on stores near schools could nearly eliminate disparities in density between neighborhoods.[4] A ban on stores near schools can be accomplished through licensing, and we know that licensing strategies with caps on the number of retailers within a geographic area can work to reduce disparities in density, as has been done in San Francisco and Philadelphia.

Health equity can be considered as a part of any tobacco control policy. For instance, with increasing momentum on Tobacco 21, places considering this type of policy may want to take a closer look at the language of their existing age of sale laws to make sure that it will not introduce or perpetuate potential equity issues in enforcement by penalizing the purchase, use, or possession (PUP) of tobacco rather than the sale of tobacco products. See Tobacco 21 Tips & Tools from the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium for more. Localities can also consider conducting a health equity impact assessment to determine what the results of any given policy may be on the ground. An approach considering social determinants of health can help practitioners ensure the benefits reach all population groups and that resources and services are distributed consistently and equally across populations so as not to exacerbate existing disparities.[1]

2. Minimum Price Policies

Continuing with the focus on health equity, price policies can also have an impact here. We know that increasing prices is the gold standard for reducing tobacco consumption, but increasing taxes isn’t the only way to do it, as increasing prices through non-tax approaches may also help eliminate disparities in tobacco use. Racial and ethnic groups that smoke at the highest rates also currently pay the least for their cigarettes.[2] Non-tax price policies (like setting a minimum “floor” price and prohibiting price discounts and coupons) can help to raise the price of tobacco and prevent the tobacco industry from circumventing the effects of tax increases.[3] Lower income smokers are more likely to purchase discount brands, so policies like minimum floor prices that raise the price of discount brands and prohibit the use of promotions that would drop the price below that minimum level could help reduce socioeconomic disparities in smoking.[4] Licensing and pricing policies can also work together in combination to decrease the impact on disparities. In 2017, we saw New York City further increase their minimum price for cigarettes from $10.50 to $13 per pack and introduce minimum pricing for all other tobacco products. Also in 2017, Robbinsdale, MN joined several other jurisdictions in Minnesota that have implemented minimum price policies for little cigars and cigarillos. And, on January 1, 2018, Sonoma County, CA’s policy that set a minimum price of $7 per pack went into effect. Expect to see more of these type of price policies in 2018.

3. Continued local action on flavors and menthol

We know that youth are more likely to initiate tobacco use with a flavored or menthol tobacco product. We also know that menthol products are easier to start, harder to quit, and scientific reviews have concluded that their removal from the market would benefit public health. In 2017, the FDA announced that they will issue an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rule Making (ANPRM) soliciting more public comments on the role that flavors and menthol play in attracting youth and potentially in users switching to a less harmful product. However, this indicates that they are not likely to take any action on menthol cigarettes or other flavored tobacco products any time soon, and folks at the local level aren’t waiting around. In 2017, we saw movement on menthol across the country, from cities and counties in California to those in Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. While some policies like those in San Francisco and Yolo County, CA prohibit the sale of menthol and other flavored tobacco products entirely, others restrict them to adult-only stores, and still others restrict them within a certain distance of youth-serving venues like schools and parks. Expect to see more policies focusing on flavors and more including menthol in 2018. See specifics about the different types of flavor policies now in place all around the country from the Public Health Law Center.

Learn more about flavored tobacco products and menthol tobacco products in our evidence summaries.

4. Tobacco 21

In 2017, the number of states with Tobacco 21 laws grew from two to five, now including New Jersey, Maine, and Oregon in addition to California and Hawaii. As of January 2018, at least 290 cities, towns, and counties in 19 states have also raised their minimum legal sales age to 21, a policy that now covers over 25% of the U.S. population. Several states, including Washington, Florida, and New Hampshire currently have bills that would raise the legal age for tobacco to 21 under consideration in their legislature. Bills have even been proposed to make the age of legal sale 21 nationwide. Given the high level of support for the policy, including among 13-17 year olds[5] and among smokers [[6, 7] we expect the list of cities, counties, and states with Tobacco 21 laws to continue to grow in 2018.

While this momentum is promising, localities considering Tobacco 21 may find it helpful to their overall tobacco control work to consider framing it as part of a broader comprehensive plan to limit youth access to tobacco and exposure the effects of tobacco marketing and/or including it as part of a licensing program that allows for both enforcement and for additional point-of-sale tobacco control interventions. See more about this in our next trend to watch…tobacco retailer licensing.

5. Tobacco Retailer Licensing as a mechanism to implement policy solutions that are most relevant and potentially impactful for local communities.

Tobacco retailer licensing (TRL) is a regulatory tool that can be used to implement a range of policies. In the simplest form, a TRL policy requires stores that want to sell tobacco to register with the city, county, and/or state. Often, they are also required to pay an annual fee to apply for or renew a license to sell tobacco products. Licensing allows for more accurate tracking of all tobacco retailers in a given locality, which can help with policy enforcement and compliance checks. It can also serve as a platform on which to build other regulations that can have a large impact on the community environment, such as restricting the density, type, and location of tobacco retail outlets. An increasing numberof localities and states are advocating for and implementing TRL policies to address youth access, disparities in retailer density, and to begin regulating e-cigarette sales and vape shops.

San Francisco currently has the most comprehensive tobacco retailer licensing policy – capping the number of licenses permitted in each of the city’s 11 districts at 45 and prohibiting any new retailer from locating within 500 feet of a school or other retailer. However, more cities are moving towards a similar model. In December 2016, Philadelphia passed a law limiting the number of tobacco retailers to 1 per 1000 people in each planning district and prohibiting new tobacco retailers within 500 feet of a school. In addition, at least 97 cities and towns in Massachusetts have instituted some sort of cap on the total number of tobacco retail outlets, and many of them also have restrictions on how close tobacco retailers can be located to schools. Several cities in California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Wisconsin also limit retailers within 500 or 1000 feet of schools.

Mapping can help communities determine the impact of any given TRL policy on the ground – e.g. how many tobacco retailers are currently located near schools in their town or where disparities in tobacco retailer density rates exist in their community. It can also help determine what TRL “plug-ins” might have the most impact on the tobacco retail environment in their community.

6. Tobacco-Free Pharmacies

6. Tobacco-Free Pharmacies

Will this finally be the year of tobacco-free pharmacies? Maybe. Truth Initiative is campaigning to get Walgreens to follow CVS’s lead in ending tobacco sales, and a recent survey says their customers agree. Meanwhile, municipalities and states don’t have to wait for Walgreens to get on board – they can prohibit tobacco sales in pharmacies all on their own, regardless of corporate policy. San Francisco, Boston, New York City, Rockland County, NY, and Rock County, MN have all done this, as have at least 14 places in California and at least 160 places in Massachusetts. The policy has also been proposed at the Massachusetts state level.

Localities can create tobacco-free pharmacies as part of a tobacco retailer licensing program by restricting the type of stores that may be issued a license to exclude pharmacies, or through a law that directly prohibits tobacco sales in pharmacies. Prohibiting tobacco sales in pharmacies is one strategy for reducing retailer density, and just makes sense to make sure retailers selling products to help treat tobacco-related illnesses aren’t also selling the very products that cause them. Learn more about tobacco-free pharmacies.

7. Lots of Local Action

Many cities and counties have been making strides in progressing point of sale tobacco control policies, and the tobacco industry is paying attention. Local action makes a difference, and the tobacco industry knows it! Already, R.J. Reynolds has spent close to $700,000 to fight San Francisco’s policy prohibiting the sale of menthol and other flavored tobacco products, a policy which will be put to a vote of the people this June. You can keep tabs on some of the arguments the tobacco industry is feeding to retailers and what ordinances they are organizing to fight via the Tobacco Ordinance Take Another Look (TOTAL) site, which was developed by the National Association of Tobacco Outlets and cigar and smokeless tobacco company Swedish Match. Don’t worry – there are plenty of resources for standing up to tobacco industry interference, which is nothing new. You can also find counter arguments from the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids in direct response to the misleading claims on the TOTAL site here.

8. Pushes for Preemption

This is not a trend we hope to see, but one to be wary of. Preemption is one of the tobacco industry’s favorite tools to limit local innovation and prevent the implementation of life-saving policies at the local level. We know that local-level policy work often precedes state-level adoption of a policy, so tobacco industries have a vested interest to keep local power limited – and they often have more influence at the state level. You can track tobacco political action committee (PAC) donations to your members of congress here. If you are in a state with preemption on many POS tobacco control policies, find out what you can do here.

9. Debate over Harm Reduction and “Reduced Risk” Products.

While the FDA has stated a goal of reducing nicotine in cigarettes to non-addictive levels, this is not the case for e-cigarettes, which are on the rise in more forms than ever. Juul e-cigarettes have now surpassed Vuse and MarkTen in popularity and are easy for youth to conceal. Look for more innovation from Big Tobacco in the e-cig world – both encouraged by the FDA to innovate with less dangerous products that smokers can switch to, and from the drive to stay in (the addiction) business from the companies themselves.[8]

An FDA panel has concluded that Phillip Morris International has presented inadequate evidence that their heat-not-burn product “iQOS” would reduce the risk of tobacco-related disease. However, the company can still submit an application to market the product in the United States, whether or not it receives a “modified risk” label. Tobacco company executives have also been quoted saying they see a future where they no longer sell cigarettes, only these “reduced risk” and alternative products instead. They’ve even started a “Foundation for a Smoke-Free World.” However, they have not announced any timeline for ending cigarettes sales, and they continue to market these deadly products aggressively both in the U.S. and in low- and middle-income countries, where they see untapped markets. The money they will contribute towards this foundation ($80 million per year for 12 years) is minuscule in comparison to the amount of money they spend marketing cigarettes and other tobacco products each year (nearly $9.5 billion per year, the large majority of which is spent at the point of sale). Read the World Health Organization’s statement on this foundation here.

Debate continues as to if and how e-cigarettes can be an effective harm reduction product, whether they can serve as an effective cessation tool, and how to keep youth from initiating nicotine and tobacco use with them. A recent congressionally mandated report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine found that e-cigarettes are likely less harmful than conventional cigarettes and may help adults quit smoking, though more research needs to be done on the specific conditions under which this can occur. While they found conclusive evidence that completely switching to e-cigarettes reduces exposure to toxicants and carcinogens found in conventional cigarettes, the report also finds that there is substantial evidence that among youth, e-cigarette use increases the risk of later smoking conventional cigarettes. The report says that the overall impact of e-cigarettes on public health is still unknown, with more research needed on both the short and long-term effects of use, as well as their relationship to cigarette use.

Debate continues as to if and how e-cigarettes can be an effective harm reduction product, whether they can serve as an effective cessation tool, and how to keep youth from initiating nicotine and tobacco use with them. A recent congressionally mandated report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine found that e-cigarettes are likely less harmful than conventional cigarettes and may help adults quit smoking, though more research needs to be done on the specific conditions under which this can occur. While they found conclusive evidence that completely switching to e-cigarettes reduces exposure to toxicants and carcinogens found in conventional cigarettes, the report also finds that there is substantial evidence that among youth, e-cigarette use increases the risk of later smoking conventional cigarettes. The report says that the overall impact of e-cigarettes on public health is still unknown, with more research needed on both the short and long-term effects of use, as well as their relationship to cigarette use.

POS policies can help reduce youth access to these products – from prohibiting self-service to restricting the sale of flavored products to making sure e-cig retailers and vape shops are licensed. It will be important to monitor how these products are marketed and promoted in the retail environment as their popularity continues. Learn more about e-cigarettes at the point of sale.

We’ll be keeping an eye on these trends, while also staying focused on combustible tobacco products (i.e. cigarettes, cigarillos, cigars). While the long-term effects of e-cigarette use are still unknown, we do know that combustible tobacco products are the leading cause of death and disease in the U.S., contributing to 480,000 premature deaths each year, and with the tobacco industry spending over $7.1 billion yearly to market these deadly products at the point of sale, we’ve got plenty of work to do fighting the “War in the Store.”

10. Partnerships to create healthier places: tobacco, food, alcohol, marijuana, and physical activity.

Intervention in the retail setting presents the opportunity to address multiple factors that influence health. The evidence behind how exposure to tobacco advertising and promotions at the point of sale contributes to tobacco use behaviors continues to grow. Across multiple studies, research has shown that youth more frequently exposed to tobacco promotion are 60% more likely to have tried smoking and 30% more likely to be susceptible to future smoking.[9] However, community interest in creating healthy retail environments continues to grow – not only with regard to tobacco but also including alcohol, food, and marijuana, as well as how the community retail environment can support physical activity. The retail environment includes both the community environment (e.g. number, type, and location of stores) and the consumer environment (e.g. what products are sold, how they are advertised, prices, etc.). A study of food retailers that also sold tobacco in three North Carolina counties found that the community and consumer environments for nutrition, physical activity, and tobacco were inter-related, indicating that measures assessing solely community level can miss characteristics of the consumer environment. [10]

Policies can address the retail environment holistically as well, tackling multiple issues at the point of sale in coordination instead of addressing each in isolation. The authors of the study in North Carolina suggest that food ordinances requiring licensed grocery stores to sell a minimum standard of healthy food, like Minneapolis’s staple food ordinance, can be expanded to place a cap on the amount of tobacco marketing allowed outside the store to reduce youth exposure.[10] Given that areas with a higher number of tobacco retail outlets are also more urban and more walkable, restricting exterior advertisements to reduce youth exposure may be more important.[10] Further improvements to the aesthetics of the store exterior, such as better lighting, removing graffiti, providing adequate trash receptacles, and preventing loitering could be incorporated as requirements for participation in healthy store programs in order to encourage walkability and active transport around the store.[10]

Monitoring and tracking of the sale of tobacco, e-cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, food and beverages can be done with the Counter Tools’ Store Audit Center. For more information on other food environment measurements, look to the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research’s Measures Registry.

For more strategies on interdisciplinary collaboration to create healthy retail environments, review:

- Case Study: Healthy Retail San Francisco

- Integrating Tobacco Control and Obesity Prevention Initiatives at Retail Outlets, published in the journal Preventing Chronic Disease.

- ChangeLab Solution’sHealthy Retail: A Set of Tools for Policy and Partnership, which includes a healthy retail Playbook, Conversation Starters, and a Collaboration Workbook.

- California Department of Public Health’s Healthy Stores for a Healthy Community

- SmokeFree Philly’s Healthy Retailer pilot project