Rural Tobacco Disparities at the Point of Sale

The United States has steadily expanded tobacco protections since 1964—with less smoke in the air and fewer advertisements for harmful products as a result. However, these health protections, including ones in the retail environment, are less likely to cover the places where people in rural areas live, learn, work, and play. The tobacco industry spends more than $1 million dollars an hour marketing their products, most of which is spent in the retail environment, and they market especially heavily in rural communities, with targeted advertising, cheap prices, and steep discounts.

This report will describe the impacts of that targeted point-of-sale (POS) marketing as well as what POS policies may help reduce the current disparities we see in tobacco use between rural and urban communities. For additional exploration of tobacco prevention and control in a rural context, see “Advancing Tobacco Prevention and Control in Rural America.”

Rural vs. Urban Tobacco Use

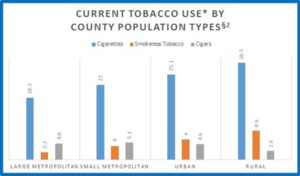

Disparities in tobacco use vary across geographic region in the United States, with rural populations bearing a greater burden. In 2020, prevalence of any tobacco product use was higher among adults living in rural areas (27.3%) compared to adults living in rural areas (17.7%).[1] In particular, cigarette smoking was higher among adults living in rural areas in the US (19.0%) compared to adults living in urban areas (11.4%) [1] and adults in rural areas used smokeless tobacco at over three times the rate of adults in urban areas (5.9% vs. 1.7%).[1] Overall, rural populations were more likely than their urban counterparts to start smoking at earlier ages, smoke in greater quantities, and be exposed to secondhand smoke .[38] While cultural and economic factors play some role in this variance, many of these inequities stem from the targeted tactics used by the tobacco industry to make tobacco products highly visible, desirable, and cheap for individuals living in rural areas across the United States.

Drivers of Rural-Urban Disparities at the Point of Sale (POS)

In 2018, the tobacco industry spent over $7.2 billion to advertise and promote their products in the retail environment. The rural retail landscape has seen heavy influence by Big Tobacco.

Advertising at the POS

Due to aggressive industry targeting, rural populations face increased exposure to advertising of certain tobacco products, particularly nonmenthol cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. [6,24] In fact, a systematic review of 43 studies found that advertising for smokeless tobacco products at the point of sale was significantly more concentrated in rural neighborhoods, compared to urban ones. [25] Moreover, a national study from 2011 to 2014 found that rural youth were more likely to be exposed to tobacco product advertising compared to urban youth. [26] Additionally, a 2018 survey of rural and urban adolescent males found that rural adolescents had higher self-reported overall exposure to tobacco advertisements, even though urban adolescents had a higher potential to be exposed to tobacco retailers during their commutes between home and school. [27]

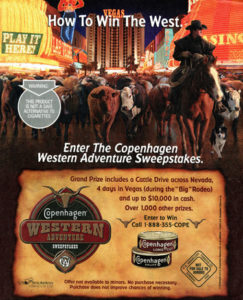

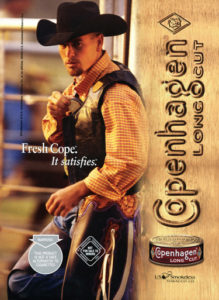

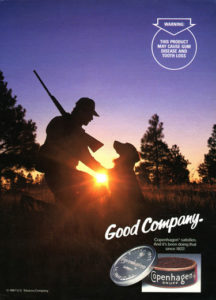

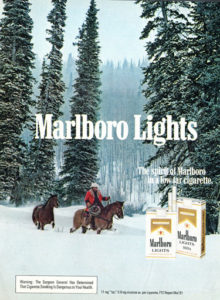

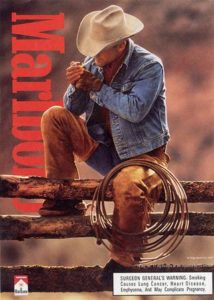

Residents of rural areas report frequent exposure to pro-tobacco messaging in gas stations, on local television channels, and at cultural and sporting events popular with rural audiences like rodeos and car races. [6] Beyond frequency and location of advertising, Big Tobacco has a pronounced history of saturating tobacco advertisements in rural markets with messaging and imagery strongly tied to typical rural themes and values. For instance, to attract and target young, rural men, the tobacco industry often places advertisements in rural retail environments that feature images of “rugged” and “manly” cowboys, hunters, and race car drivers, hand in hand with tobacco products. [1] These images and the accompanying pro-tobacco messages exploit such rural values as “self-reliance” and “resiliency”. [28] A study from rural Appalachian Ohio found evidence of the effectiveness of these targeted ads, with men and boys reporting a strong belief that smokeless tobacco was “a rite of passage in the development of their masculine identity”. [29] Apart from a focus on masculinity, ruggedness, and resilience, smokeless tobacco advertisements in rural areas are often intertwined with images of nature and farmlands to tap into rural values and sentiments around agriculture and rural landscapes. [6] Some evidence suggests that these types of advertisements helped to further propagate pro-tobacco norms in these rural areas. [6]

Rural populations are also heterogenous, and it is important to remember that certain subpopulations residing in these areas may be vulnerable to additional industry targeting and manipulation; low-income, African American and Black individuals, as well as Tribal residents, who live in rural areas may be at the intersection of multiple industry tactics. More information can be found on these populations on our pages, Native Americans & POS Tobacco and Disparities in Point-of-Sale Advertising and Retailer Density, but specific mention should be made here on the particular intersection between rurality and Tribal populations. In rural, Tribal areas, Big Tobacco heavily utilizes images commonly associated with Tribal culture and spirituality in their tobacco product advertisements. As well, the tobacco industry has a history of sponsoring Tribal events and funding promotions and price reductions on tobacco products in Tribal retail outlets and casinos. [6] In any case, the tobacco industry has, for years, aggressively marketed to rural populations and subpopulations, particularly through targeted advertising designed to link tobacco use with rural values and identities.

Product Availability, Price Promotions, and Discounts

Disparities at the point of sale go beyond just advertising; evidence has shown variations in product availability, discounts, and product prices between rural and urban communities as well. In a study from 2017 of 1,276 licensed tobacco retailers in California, researchers examined differences in availability and prices of tobacco products between stores categorized at the county and tract levels as either rural or nonrural. [30] In this study, rural stores were 2.1 times more likely to sell chewing tobacco and 2.5 times more likely to sell roll-your-own tobacco, compared to nonrural stores. As well, money went further in rural stores, with rural stores selling larger packs of cigarillos for less than $1 and also selling the cheapest pack of cigarettes for an average of $0.21 less than the nonrural stores. In rural stores, discounts on chewing tobacco were 1.81 times more likely to be advertised than in nonrural stores. Another study, using a sample of over 100 urban and 100 rural tobacco retailers in Ohio, found that the cheapest packs of cigarettes were, on average, sold for the lowest prices in rural areas with the highest percentage of resident living below poverty level – a finding which was not mimicked in urban Ohio. [31] In the recent past, corporate decisions to continue or discontinue the sale of tobacco products has also had an impact on tobacco retailer density, and thereby the availability of tobacco products, in urban and rural locations; for instance, as a result of CVS discontinuing tobacco sales, and Family Dollar and Dollar General, the two largest dollar store chains which have expanded rapidly into rural communities, initiating tobacco product sales, rural counties saw an increase in tobacco retailer density from 2012 to 2014 that was eight times greater than in urban counties .[39]

Differential Tobacco Control Policies

Rural areas, especially those that are tobacco-growing, may face differential coverage from tobacco control policies.[6] Studies have shown that states with larger proportions of rural residents are less protected by comprehensive smoke-free air and tobacco excise tax legislation.[6] The American Lung Association’s report, Cutting Tobacco’s Rural Roots, suggests that at the local level, smoke-free legislation, in particular, may be rarer in rural areas.[32] In general, analysis of tobacco control policies at the local level shows less presence of tobacco-related policies in some rural communities. [6] Compared to urban areas, rural areas may also have fewer resources to stringently enforce tobacco control policies.[19] Rural residents make up 20% of more of the population of each state in “Tobacco Nation,” a region which Truth Initiative has identified, comprised of twelve states, where smoking rates are higher than both the national average and higher than in many countries with the highest global smoking rates. This region also has less comprehensive and restrictive tobacco control policies than much of the rest of the United States. [4, 6] In general, prices of tobacco are lower in jurisdictions lacking excise taxes and other non-tax legislation on tobacco products, such as minimum price laws and bans on price discounting, that would raise the product prices; in Tobacco Nation where these policies are less prevalent, cigarette prices are 18% less at an average of $6.50 per pack, compared to the national average price of a pack of cigarettes at $7.95. As well, the average excise tax on cigarettes is significantly less in Tobacco Nation compared to the rest of the nation. [4]

The difference in tobacco control legislation is especially true in tobacco-growing states. Along with their strong cultural and economic focus on tobacco as a cash crop, these states often lag behind non-tobacco growing states in implementation of strong, progressive tobacco control policies [19] Furthermore, research has found that states with strong ties to the tobacco industry (which tend to be states with large rural, agricultural sectors) tend to devote fewer resources to tobacco prevention and control. [6] A survey of 253 local health department in rural areas found that political conservativeness, heavy agricultural and economic focus on tobacco, cultural emphasis on individual freedoms, and limited funding for tobacco programs were all mentioned as barriers to implementing tobacco control programs and policies in these local, rural areas.[40]

In addition, 7 out of 10 US states with the highest proportion of rural residents have preemptive state laws that prevent local communities from establishing stronger local tobacco control regulations. Local level policy-making is an effective way to reduce tobacco use through strategies that are aligned with the local community’s needs, context, and values. Consequently, Big Tobacco works tirelessly to limit local control and action by lobbying for federal and state policies that include language specifically prohibiting local governments from enacting their own policies that are more comprehensive and stringent than policy rules and regulations at the federal or state level. Overturning or reversing preemptive state laws can be a long and cumbersome process, but jurisdictions have been successful in rescinding preemptive provisions on local tobacco control policies. Read more about tobacco point of sale preemption and options for point-of-sale activities in states and localities that are preempted.

While overall rural states and local communities are disproportionately covered by weaker tobacco control laws, some states with predominately rural populations have seen major successes in tobacco control at both the state and local level. [6] For instance, Maine, which has a rural population of over 25%, has extremely comprehensive smoke-free air laws and also raised the minimum legal sales age of tobacco products to 21 in July of 2018, roughly a year and a half before the federal legislation that expanded Tobacco 21 across the nation.[6]

Prevalence Data

Rural-Urban Disparities in Adult Tobacco Use

Prevalence data from 2016 shows that cigarette smoking was higher among adults living in rural areas in the US (28.5%) compared to adults living in urban areas (25.1%). [1] In past years, as clean indoor air policies became more commonplace, this gap in tobacco use between rural and urban populations became more pronounced.[3] Between 2007 and 2014, unadjusted cigarette smoking prevalence dropped significantly from 24% to 20% in urban populations, while rural populations saw an insignificant and only slight decrease in smoking prevalence in the same timeframe.[3]

While cigarettes still remain the most commonly used tobacco product by adults across the United States, rural populations show higher rates of both cigarette and smokeless tobacco use; in contrast, urban populations show higher rates of cigar, cigarillo, and hookah use. [1, 3] Data from Wave 1 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health [PATH] Study (2013-2014) found no significant difference in prevalence of e-cigarette, pipe, or menthol cigarette use between urban and rural populations. [17] As well, adults living in rural areas who smoke are more likely to smoker larger quantities of cigarettes (15+) per day, compared to adults living in urban areas that smoke. [1]

Looking at a broad swath of the rural United States, smoking rates in “Tobacco Nation”, which hover around 21% for adults, far exceed the national average adult smoking rate of 15%; the average adult smoking rate across “Tobacco Nation” reaches levels comparable to many countries across the globe with some of the highest rates of smoking.[4] While these rural-urban disparities in tobacco use are partly associated with certain sociodemographic risk factors characteristic to rural populations like employment status, income level, and educational attainment, when these sociodemographic risk factors are controlled for during analysis, the disparities in tobacco use and associated tobacco-related burdens still remain between rural and urban populations.[5]

Rural-Urban Disparities in Adolescent Tobacco Use

Cigarette use has declined for both urban and rural adolescents over time but more so for urban adolescents.[18],[19] Despite the overall decreases, rural adolescents are still 1.4 times more likely to use cigarettes and 3 times more likely to use smokeless tobacco products than urban adolescents.[16],[19] In contrast, urban adolescents are 0.8 times more likely to use hookah tobacco.[19],[20] As well, rural adolescents are more likely than suburban and urban adolescents to begin smoking cigarettes at a younger age and to smoke cigarettes daily. [1] Surveys conducted on rural and urban adolescents between 2008-2010 and 2014-2016 depict significant differences in smoking prevalence. Between 2008 and 2010, 10.9% of rural adolescents smoked while 8.3% of urban adolescents smoked. From 2014 to 2016, the prevalence was 7.3% and 3.7%, for rural and urban adolescents, respectively.[20] Even as prevalence declined for both populations, the gap between rural and urban youth smoking rates widened. Of note, this gap persisted even after adjustment for socioeconomic factors that may contribute to smoking.[20]

Additionally, a study examining adolescents in Florida in 2012 found that rural adolescents have a younger tobacco initiation age and also report smoking more, both on a daily basis and consistently in the past 30 days. [33] Despite the overall decline in adolescent cigarette use across America over the past few decades, rates of electronic cigarettes have been on the rise for American youth; e-cigarette use is now more common nationally among high school students than cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, and these same trends have been found with adolescents in rural areas.[11]

Rural-Urban Disparities in Sub-Population Prevalence

Data from the 2015-2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health depict the following rural-urban disparities in various sub-populations:[34, 6]

- 33.6% of rural non-Hispanic Whites reported past-month tobacco use, 26.2% reported past-month cigarette use and 8.5% reported past-month smokeless tobacco product use. Contrastingly, 26.4% of urban non-Hispanic Whites reported past-month tobacco use, 21.2% reported past-month cigarette use and 3.8% reported past-month smokeless tobacco product use.

- Rural Hispanics were more likely to report past-month tobacco product and cigarette use than urban Hispanics.

- 46.3% of rural individuals living in poverty reported past-month tobacco use, compared to 33.5% of urban individuals living in poverty. Rural residents living in poverty also had higher rates of past-month cigarette and smokeless tobacco use.

- Rural individuals living with a mental illness showed higher rates of past-month tobacco, cigarette, and smokeless tobacco use, compared to their urban counterparts.

- Significantly more rural pregnant women used tobacco products in the last month compared to urban pregnant women.

- Rural-urban differences in past-month tobacco use and cigarette use were also seen in veteran and LGBTQ+ populations.

Regional Variations in Rural Tobacco Use

Rural communities are heterogenous, and as such, rural tobacco use does have significant variations dependent on region in the US. According to data from 2012-2013, rural-urban disparities appear more so in the Northeast, South, and in low-income rural communities across the Midwest. [6]

POS Policy Options

Knowing what types of tobacco products are popular and why these disparities exist between urban or rural populations can help with the construction and advocacy for comprehensive intervention programs and legislation. As differences persist in the advertising, promotion, and availability of tobacco products based on the tobacco industry’s geodemographic targeting, regulating tobacco products in the retail environment could help to reduce disparities in tobacco use and tobacco-related morbidity and mortality, ultimately leading to more equitable health outcomes between rural and urban populations, as well as sub-populations within rural communities. Below are some suggested policy options for state and local entities. While areas with large rural populations could particularly benefit from these, the policies mentioned below can be impactful and successful regardless of geodemography.

Pricing Policies

In addition to raising excise taxes, which is the gold standard for increasing tobacco prices at the point of sale, non-tax-based legislation like implementing or strengthening minimum price laws and prohibiting price promotions such as coupon redemption, multi-pack discounts, and ‘buy one get one’ offers would limit the industry’s ability to keep tobacco prices low for rural consumers. Price is one of the most influential factors affecting smoking purchasing behaviors and tobacco use, and these industry promotional strategies are designed to keep tobacco prices low for consumers even when jurisdictions implement excise taxes that raise the price of tobacco products. [36] The US Surgeon General noted that raising prices of tobacco products is “the single most effective method for improving the public health outcomes of decreased smoking prevalence and initiation, reduced consumption, and increased, sustained cessation.” [35] Individuals living in rural areas, and especially low-income rural areas, see some of the cheapest prices for tobacco products in the United States; these low prices allow consumers to stay hooked on tobacco without breaking the bank. As well, a study conducted in Ohio in 2018 found that people bought greater quantities of cigarette packs if they lived farther from a tobacco retailer and if they could use a price promotion. Travel distances are generally larger in rural areas compared to urban areas so rural residents have a tendency to buy substantially more tobacco products in a single purchase.[37] These findings indicate that raising the price of tobacco products, through excise taxes and non-tax approaches, have the potential to reduce disparities in cigarette and smokeless tobacco use and the associated burdens in rural areas. Learn more about pricing policies here.

Restricting POS Advertising

Restrictions and reductions in tobacco advertisements in the retail environment can limit exposure to extremely targeted pro-tobacco imagery and messaging. While First Amendment commercial free speech concerns do not allow the regulation of the content of advertising, jurisdictions can regulate the total amount of advertising allowed on storefronts through content-neutral sign ordinances that limit the space all ads (regardless of content) can cover to a certain percentage (e.g. 25%) of retailers’ window space or exterior. Learn more about what this looks like in Orangeburg, SC. To work within the First Amendment restrictions, localities and states can also restrict advertising by time, place, and manner. The Public Health Law Center’s guide for restricting tobacco advertising suggests that these restrictions based on time, place and manner could potentially be effective for both rural and urban communities, and especially rural and urban youth. For rural youth who see fewer tobacco retailers on a daily basis, limiting the proximity of advertisements to the point-of-sale may prove beneficial. Learn more here.

Restricting the Number, Type, and Location of Tobacco Retailers

This infographic illustrates community strategies to potentially decrease tobacco use and curb exposure to tobacco marketing by limiting tobacco retailer density. These strategies may remove some retailers from rural areas, but research also suggests that many of these strategies may be more effective in urban areas. However, some rural areas such as Rock County, MN have found success in prohibiting the sale of tobacco in pharmacies and prohibiting tobacco retailers from locating near schools or other youth-oriented facilities. In addition, a modeling study conducted in Ohio found that capping the number of tobacco retailer licenses issued in a geographic area (e.g. to 1 per 1,000 people) would be an effective way to reduce rural-urban disparities in tobacco retailer density; capping policies may be more effective in rural areas than restrictions on proximity to schools or other retailers given that retailers are more spread out. [23]

Restricting the Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products

The 2009 Family Smoking and Tobacco Prevention Act banned the sale of cigarettes with “characterizing” flavors other than menthol or tobacco. However, other flavored tobacco products (smokeless tobacco, little cigars and cigarillos, e-cigarettes, hookah, etc.) have remained on the market and become much more prevalent in recent years. National data show that 80% of youth who have ever used a tobacco product started with a flavored product. While studies examining rural tobacco use of flavored products in particular are more limited, implementing policies that limit the availability of flavored tobacco products would likely help reduce adolescent rural tobacco use, as rates of adolescent e-cigarette use, especially of the flavored variety, have inclined in recent years. Early adopters of most flavored tobacco sales restrictions have been primarily urban to date, so to ensure rural areas are equitably covered by these policies as well, special attention may be needed to raise awareness regarding the effectiveness and importance of these types of policies on rural youth. Implementing flavored tobacco sales restrictions at the local, state and/or federal level with adequate enforcement mechanisms and funding could help to ensure that rural areas do not face yet another policy coverage disparity.

Restricting Product Placement

POS product displays can increase the perception of availability of tobacco products, increase brand recognition, and encourage impulse purchases, which ultimately increase the likelihood of smoking and undermine quit attempts. Restricting tobacco product placement would help limit the impact of these types of industry marketing strategies. Ensuring products, including e-cigarettes and cigarillos, are not available in self-service displays could help restrict youth access to these products in both urban and rural stores alike. While other strategies to limit product placement, such as display bans, have run into legal issues in the United States, they have been successful internationally and, if implemented in the U.S., could have an impact on rural tobacco use by reducing youth exposure to tobacco product displays in stores. Eliminating product displays could also help improve cessation success rates across rural and urban environments by reducing impulse purchases triggered by exposure to products in stores. Though overall product placement restrictions may not address the present disparities between urban and rural communities, the restrictions are commonsense measures that can help reduce tobacco product visibility and youth exposure. Learn more about restricting product placement here.

Restricting Product Packaging

Restricting tobacco packaging that entices new, current, and recent former smokers may help reduce the influence of the tobacco industry in the retail environment. While under federal law, cigarettes must be sold in packs of 20, no federal standard exists for cigars. This loophole allows companies to sell cigars and cigarillos at very low prices, making them extremely appealing to price sensitive shoppers like youth and low-income adults. However, localities can establish both a minimum pack size and minimum price for cigars and cigarillos. While requiring cigarettes to be sold in plain packaging has seen success internationally, commercial free speech protections would likely prevent such regulations in the United States. Based off the 2018 survey of adolescent males in rural and urban Ohio, limiting product packaging in the retail environment may pose a promising barrier to stopping tobacco exposure and thus initiation among rural adolescents. Because rural male adolescents more frequently visit tobacco retailers, reducing their overall exposure to tobacco products may limit their likelihood of tobacco initiation. Learn more about restricting product packaging here.

Next Steps for Reducing Rural-Urban Tobacco-Related Disparities

Certain strategies may help build an infrastructure to eliminate the apparent tobacco-related disparities along urban and rural lines. These strategies can include:

- Conducting up-to-date surveillance to identify the populations disproportionately affected by tobacco use.

- Assessing the macro and micro retail environment to ascertain disparities in point-of-sale marketing.

- Conducting a legal analysis at the state and local level, as well as community needs assessment, to gather a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the legal, political, environmental, and cultural facilitators and barriers to policy change.

- Ensuring health equity is a constant and integral part of strategic planning for state and community organization. Learn more:

- CDC’s “Best Practices User Guides – Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control”

- Massachusetts Public Health Association’s “Health Equity Policy Framework”

- CounterTobacco.org evidence summary, “Health Equity and Point-of-Sale Tobacco Control Policy”

- Providing geodemographically and culturally tailored technical assistance and training to local partners. Learn more through “A controlled community-based trial to promote smoke-free policy in rural communities.”

- Building readiness and capacity for policy work and engaging stakeholders. Learn more through the CDC’s “Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs.”

- Planning ahead for policy implementation, enforcement, challenges, and unintended consequences. Learn more through the Public Health Law Center’s “Framework for Analyzing Tobacco Policy Interventions.”

Additional Resources

- Advancing Tobacco Prevention and Control in Rural America, University of Southern Maine, National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, & National Network of Public Health Institutes

- Cutting Tobacco’s Rural Roots, American Lung Association

- Rural Health and Well-Being in America, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- Addressing Rural Cancer Health Disparities, Geographic Health Equity Alliance

- Tobacco Prevention and Control Efforts in Rural America: Current Local Health Department Successes and Challenges, NACCHO

- Watch the associated webinar here.

- Tobacco Control Efforts in Rural America: Perspectives from Local Health Departments, NACCHO

- “The Real Cost” Smokeless Tobacco Prevention Campaign, FDA

- Rural Tobacco Control and Prevention Toolkit, Rural Health Information Hub

- Geographic Regions and Commercial Tobacco: Health Disparities and Ways to Advance Health Equity, CDC