Evaluating Point of Sale Tobacco Control Policies

States and communities across the country are increasingly passing a wide variety of policies designed to restrict the retail availability and marketing of tobacco products and ultimately lessen the inequitable burdens of tobacco-related death and disease. Once a policy is passed, it’s important to evaluate the law’s effectiveness to assess if the law is achieving the intended benefits. Policy evaluation applies the same evaluation guidelines used to measure the success of tobacco control programs or initiatives, but focuses specifically on examining the content, implementation or impact of a policy.

Policy evaluation is an important tool for demonstrating the value and potential challenges of a policy by measuring its ability to result in the intended impact. In addition, policy evaluation helps to assess support for, enforcement of, and compliance with implemented policies and identify potential gaps, deficiencies, or unintended impacts. All of this information is key to informing the evidence for future policy or any modifications needed for existing policies.

Policy evaluation teaches the valuable lesson that there is no ‘one size fits all’ policy and impacts often differ across communities. As an example of how point-of-sale policy outcomes may differ based on community demographics and history, a modeling study in Ohio examined the equity impact of different licensing plug-ins related to tobacco retailer density in rural and urban communities across the state. Findings showed that policies that place a cap on the total number of retailers permitted in a geographic area worked the best to reduce disparities in retailer density in rural areas, whereas setting a minimum distance that retailers can be located from schools had the biggest impact on disparities in urban areas. On the other hand, prohibiting tobacco sales in pharmacies actually widened existing disparities and therefore had an inequitable impact. [1]

Planning for policy evaluation

In order to be most effective, policy evaluation should be planned well in advance of policy implementation. The CDC’s Tobacco 21: Policy Evaluation for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs provides a six step framework for planning a policy evaluation that was used to guide the section below:

Step 1: Engaging Stakeholders

In addition to traditional evaluation staff, potential stakeholders to engage in planning include policy and subject matter experts. Those involved in policy implementation and enforcement are also important partners to involve from the start. Increasingly, policymakers and evaluators are seeking ways to include community members whose lives are most affected by a policy issue—such as residents in the neighborhood and small business owners—throughout the policy process, including evaluation activities.

For guidance on how policymakers, community groups, and public health practitioners can measure the effectiveness of community engagement efforts undertaken through policy partnerships, see ChangeLab Solutions’ Guide to Evaluating Policy Processes for Equity.

Step 2: Describing the Policy Being Evaluated

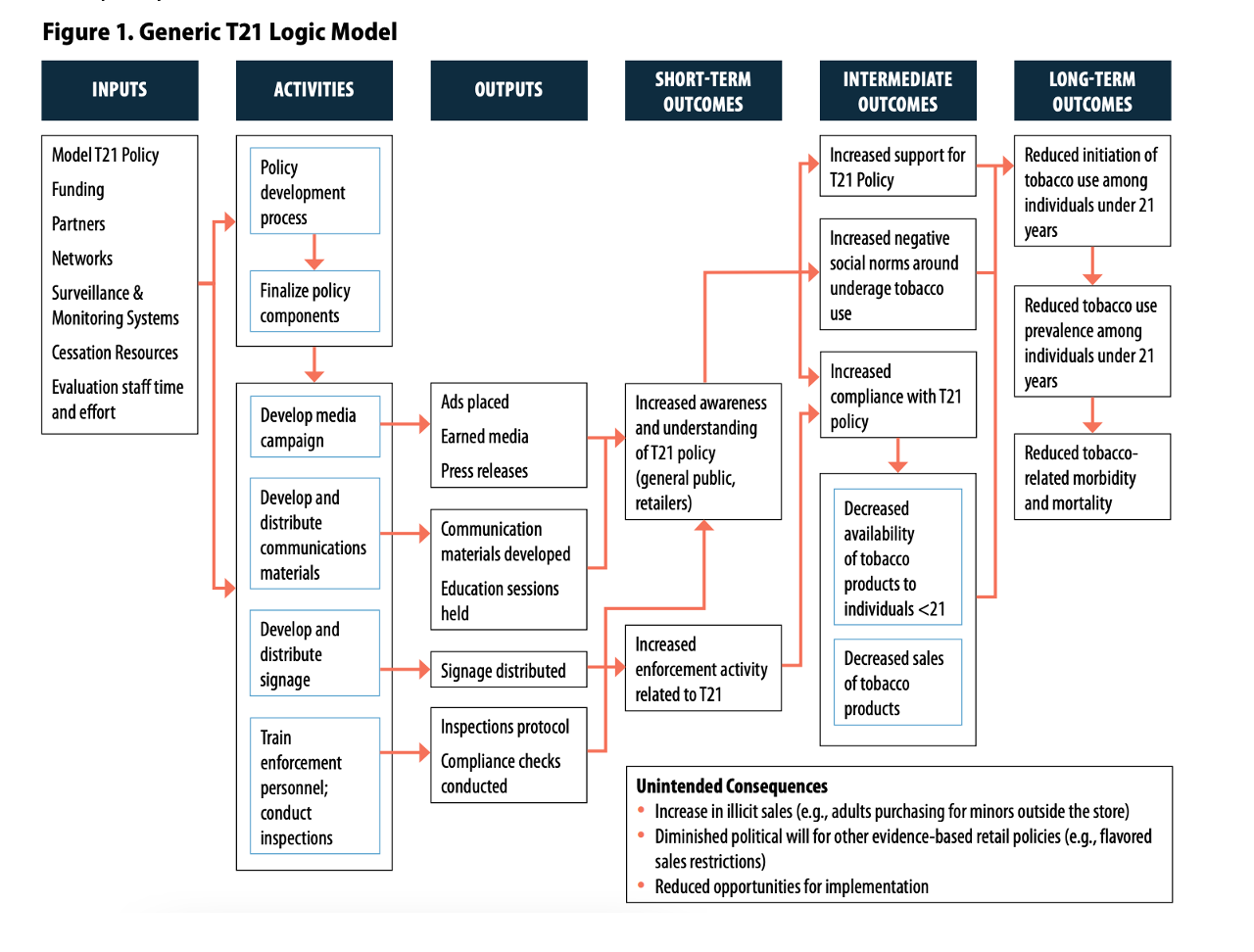

A full understanding of policy content and intended outcomes is necessary for proper evaluation. Policy content includes components such as policy definitions (e.g., definitions of tobacco products), enforcement authority and penalty structure, and effective dates. Intended outcomes may be short-term, intermediate term, or long-term. A logic model can be a useful tool for graphically displaying the theorized pathways of change resulting from an implemented policy.

Step 3: Focusing the Evaluation

A comprehensive evaluation plan generally involves evaluating multiple aspects of a policy:

- Policy content: How does the policy content compare with model policy language? Will the policy, written and expressed, produce the desired result?

- Policy implementation: Did the policy pass? Did it roll-out as intended? Were there any barriers to implementing it? How were community partners involved in the process?

- Policy impact: Did the policy produce the intended result or outcome? How did the implemented policy affect health disparities?

There are a number of data measures that can be used to determine if a policy is having the intended impact. These measures, sometimes referred to as indicators, can help you understand what changes took place following policy implementation. It is important to understand how changes in these measures may differ among various disaggregated segments of the data, for example, when broken out by different demographic groups, which may reveal inconsistencies in reach and equity. Examples of indicators that are relevant to POS policy include:

- Product availability

- Pricing

- Price promotion availability

- Advertising presence (note that even policies that don’t directly regulate advertising can result in a decrease in advertising for tobacco products – e.g. retailer density limits; flavored tobacco products bans)

- Number of retailers selling tobacco

- Number of retailers near school

- Density of retailers

- Retailer violations

- Youth and adult tobacco use rates (across products, demographics)

Unintended consequences are also an important consideration that can be identified through policy evaluation. Examples of intended consequences to point-of-sale policies might include:

- Increase in illicit sales (e.g., adults purchasing for minors outside the store or illegal sale of banned products)

- Increase trafficking or cross-border purchases (e.g., purchasing from a state with lower prices or without flavor bans)

- Exacerbated disparities (e.g., more significant decrease in retail density in neighborhoods where density was already low)

- Diminished political will for other evidence-based retail policies

As an important reminder, the way we collect and analyze data involves making choices. These choices have the potential to reinforce an individual’s perspective in a way that affects the data outcomes and ultimately the decisions or actions based on them. For help making these decisions in a systematic way that centers equity goals, see We All Count’s Data Equity Framework.

Steps 4-5: Gathering Credible Evidence and Justifying Conclusions

Sources of evidence may include:

- Store Assessments: A number of the indicators listed above, including product availability, pricing, and promotion, can be captured through store assessments. Regularly conducting store assessments can be a powerful way to see how the retailer landscape changes over time, particularly when a point-of-sale policy goes into effect.

- Sales data: Sales data from retailers, often available for purchase, can illustrate changes in product sales that may be attributable to policy change.

- Health behavior data: There are a number of state and federal surveys conducted annually that provide data on health behaviors. For example, CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) can point to how reported tobacco use compares before and after policy implementation.

- Public opinion polling and other sources of data and stories that involve direct community participation by those whose lives are most affected by the policy issue. Learn more about how community participation can inform the evaluation process in ChangeLab Solutions’ Guide to Evaluating Policy Processes for Equity.

- Compliance data: Compliance data provides insight on the retailers violating tobacco control policies. Synar and FDA compliance data indicates if retailers sell tobacco to minors. FDA compliance data is publically available and can be sorted by state, city or zipcode. Additionally, state or local enforcement data should capture adherence to other point-of-sale policies.

- GIS mapping: GIS mapping can be a valuable tool for analyzing changes in tobacco related disparities and visualizing the impact of point-of-sale policies, such as a reduction in retailer density.

Step 6: Applying Policy Evaluation Results

Evaluation results can be useful to a variety of audiences. Stakeholders from the community directly impacted by the policy, including members of the general public, will be interested in understanding the measures that indicate whether or not a policy was a success—indeed, they may have their own data and/or experiences that contribute to a more complete story of how the policy has affected their community. Results should inform on-going implementation of the policy, and may elicit ideas for ways to change to the policy over time to maintain and improve its effectiveness and intent. This includes reexamining policy language as needed. In addition, results are key to informing future national, state and local policy implementation efforts. In order to make results most useful, evaluators should consider how to tailor the sharing of results with different groups.

Examples of POS policy evaluations

Licensing, Zoning and Retailer Density

- [MA] Impact of Massachusetts law prohibiting flavored tobacco products sales on cross-border cigarette sales

- [MA] Short-term impact of a flavored tobacco restriction: Changes in youth tobacco use in a Massachusetts community, American Journal of Preventative Medicine

- [MA] Impact of flavoured tobacco restriction policies on flavoured product availability in Massachusetts, Tobacco Control

- [MA] Evaluating tobacco retailer experience and compliance with a flavoured tobacco product restriction in Boston, Massachusetts: Impact on product availability, advertisement and consumer demand, Tobacco Control

- [MA] Archived Webinar: Flavored Tobacco Policies & Evaluation – A Massachusetts Case Study

- [MN] A tale of two cities: Exploring the retail impact of flavoured tobacco restrictions in the twin cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota

- [RI] Changes in cigar sales following implementation of a local policy restricting sales of flavoured non-cigarette tobacco products

- [OH] Evaluation of Restrictions on Tobacco Sales to Youth Younger Than 21 Years in Cleveland, Ohio

- [US] A Rapid Evaluation of the US Federal Tobacco 21 (T21) Law and Lessons From Statewide T21 Policies: Findings From Population-Level Surveys

Tobacco POS policies such as density and proximity policies, tobacco retail licensure, raising the price of tobacco products, and regulating flavored tobacco products have been proven to be effective for addressing tobacco at the point of sale and addressing health disparities. Many pre-policy evaluations help illustrate the need for implementing POS policies such as reducing disparities in tobacco retailer density and disparities in tobacco use [OH] and reducing tobacco-related health inequities [MN].

While there is substantial evidence to support the effectiveness of these POS policies, more evaluation is needed of POS policies that have been implemented. Has your community evaluated a policy that addresses tobacco at the point of sale? If so, we’d love to hear from you! Contact info@countertobacco.org to share your story.