Rebutting Economic Arguments Against POS

The tobacco industry often argues against policies that promote health, citing devastating financial consequences for retailers, and in particular, for convenience stores that sell tobacco products. Tobacco control policies focused on the retail environment, such as bans on price discounts, coupon redemption and the removal of tobacco products from pharmacy shelves have been the target of significant push back. Economic concerns raised typically center around job loss, store closures and the financial burden incurred by retailers to comply with progressive point-of-sale (POS) policies.

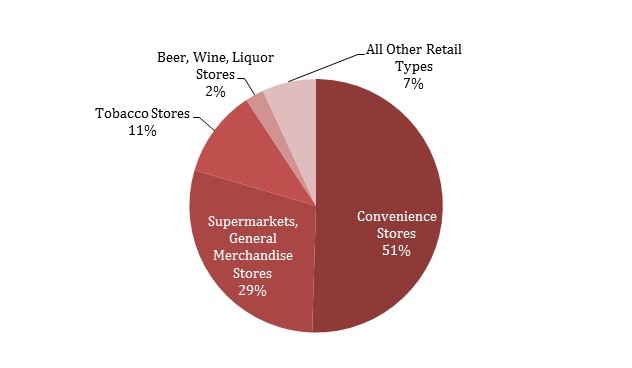

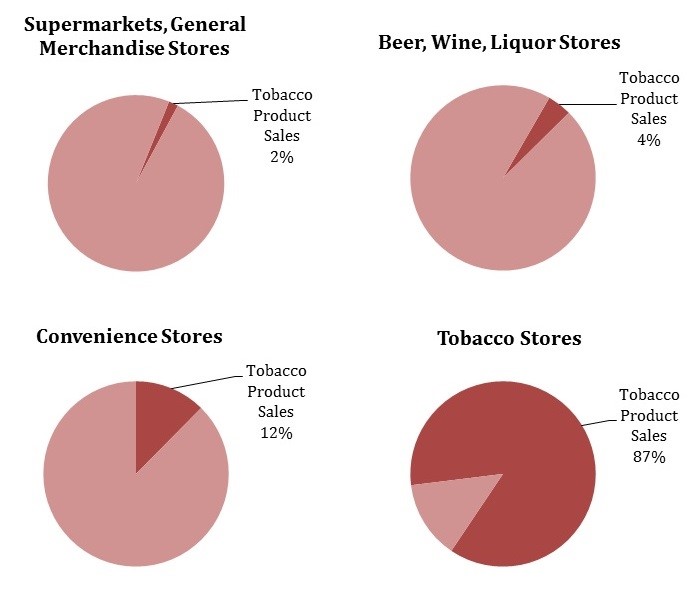

A majority of tobacco industry revenue funnels through retailers. According to data from the US Department of Commerce, in 2002, 93% of all tobacco sales were generated by the following retail categories: 1) convenience stores, 2) supermarkets and general merchandise stores, 3) tobacco stores and 4) beer, wine and liquor stores (see Figure 1)[1]. Sales data reported were collected from retail establishments with at least one or more paid employees[1] As outlined by Table 1, nearly 51% of all tobacco retail sales, equaling approximately $26 billion, occurred in convenience stores.[1] 95% of convenience stores sell tobacco products and tobacco sales comprised 12.4% of convenience store sales in 2002 (See Figure 2).[1] The data reveal the importance of the convenience store to the tobacco industry as it is a primary channel for tobacco product distribution. However, it is important to note that tobacco is not the biggest driver of profits for convenience stores – prepared foods and packaged beverages are more profitable.[6] In 2016, while 36% of in-store sales were from tobacco, only 18.2% of profits were from tobacco. In comparison, prepared foods were 22% of sales, but 35% of profits, and packaged beverages were 15% of sales but 18.5% of profits. In addition, while a common industry argument against sales restrictions on tobacco is fear of reduced revenue for retailers and that tobacco brings in people to purchase other goods, such as food and beverages. However, a 2012 study done in Philadelphia low-income corner stores found that most tobacco purchases did not include other items.[2] Total amount spent on other items were the same regardless of whether tobacco was also purchased.[2]

Table 1: 2002 Sales Revenues for Grouped Retail Establishments for all 50 US States

*Tobacco products are defined in line with North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code 20150 “Cigars, cigarettes, etc. & smokers accessories excluding sales from vending machines.

**Includes convenience stores attached to gas stations

Figure 1: Tobacco Product Sales Generated by Retail Category, 2002

Source: Based on data from US Census of Retail Trade 2002; Ribisl KM, Evans WN, Feighery EC. Falling cigarette consumption in the U.S. and the impact upon tobacco retailer employment. In: Bearman P, Neckerman K, Wright L, eds. Social and Economic Consequences of Tobacco Control Policy. New York:Columbia University Press, 2011

Figure 2: Percent of Total Annual Sales Generated by Tobacco Products by Retail Category, 2002

Source: Based on data from US Census of Retail Trade 2002; Ribisl KM, Evans WN, Feighery EC. Falling cigarette consumption in the U.S. and the impact upon tobacco retailer employment. In: Bearman P, Neckerman K, Wright L, eds. Social and Economic Consequences of Tobacco Control Policy. New York:Columbia University Press, 2011.

Responses to Economic Concerns Surrounding Tobacco Control

Economic Concern #1: Increased financial burden among smaller retailers

Due to the lower overall profit margins earned by locally owned retail outlets, POS tobacco control measures like display bans are often met with strong opposition from smaller retailers. Owners of these outlets fear that the implementation of tobacco display bans will result in reduced sales and the loss of tobacco industry financial incentives to display ads at the point of sale. It is also argued that the additional costs to implement enclosures necessary to comply with the requirements of a tobacco display ban can be costly for small retailers”.

Reality

Retail display bans have been implemented in several countries such as Iceland (2001), Thailand (2005), Ireland (2009) and several Canadian provinces.

Economic Impact of Display Ban in Canada

In Canada, convenience stores feared that the enforcement of a tobacco display ban would ruin retail sales. [3] In Saskatchewan, Canada, a tobacco display ban was implemented in 2002 and then lifted during October of 2003 to 2005 due to a court appeal. In 2005, the tobacco display ban was reinstated. During 2000-2005, Saskatchewan tobacco sales only fell slightly below national Canadian sales.[3] Thomson and colleagues indicated that a drastic drop in sales was likely not observed because the economic impact of changes in experimentation, initiation and addiction will take several years to manifest. This delayed effect should allow retailers time to diversify product offerings in order to compensate for the impending decrease in tobacco sales. [3]

Furthermore, after the implementation of display bans, tobacco industry reports submitted to Health Canada reveal that annual payments to Saskatchewan tobacco retailers experienced modest decreases: 3% between 2004 and 2005, and 8% between 2005 and 2006. [3] Although a slight decrease in annual payments was observed, retailers were still receiving incentive payments from the tobacco industry after the display ban was implemented. This demonstrates that the tobacco industry’s incentive program originally designed to pay retailers to display their POS advertisements evolved into paying retailers to handle and sell the full range of their tobacco product brands. [3]

Economic Concern #2: Significant job loss to the retail industry

It is often cited that decreased production and sales of tobacco products will decrease job availability and result in negative consequences for the economy. [4] A typical tactic of the tobacco industry is to highlight the interdependence that the economy shares with tobacco production in order to raise concerns surrounding the financial impact of decreasing tobacco product sales. [4] Since US retail outlets selling tobacco employ several million individuals, job loss is a major concern when considering the economic impact of tobacco control efforts. [1]

Research’s Response:

In 2011, researchers Ribisl, Evans and Feighery sought to understand the economic impact of markedly reducing US cigarette consumption on retail establishments selling tobacco products by creating a model to mimic the implementation of the Institute of Medicine’s 2007 tobacco control recommendations To conduct the analysis, the researchers used past data on cigarette sales, cigarette tax rates, and employment from 1990 to 2004 to estimate what would happen to retail jobs and revenues if there was a large drop in smoking rates.

The study found that overall employment for the US retail industry would be expected to remain relatively unchanged despite a substantial decrease in cigarette consumption.[1] While some stores, such as tobacco outlets, will experience a greater burden of unemployment rates, other store types selling a variety of goods other than tobacco will be able to drive profits from their other product offerings.[1] Money that was once spent on tobacco products are predicted to shift to other services and merchandise.[1] Because profits driven by other products increased, lowered tobacco sales at stores did not harm levels of overall retail employment.[1]

Economic Concern #3: Increased store closures among smaller retailers

Another fear capitalized upon by the tobacco industry to blockade POS policies is the notion that tobacco control policies will cause small retailers, such as convenience stores, to shut down their businesses due to decreased revenue caused by lost tobacco sales.

Research’s Response:

To determine if tobacco control policies have a negative impact on convenience store businesses, Chaloupka and Huang analyze the impact of smoke free air policies and state cigarette excise taxes on the density of convenience stores in the US. Convenience store density is determined by the opening and closing of stores, which is related to a store’s profitability. Prior research has established that both smoke free air policies and higher state excise taxes decrease tobacco use.[5] Analyzing the convenience store density trend between 1997 and 2009 revealed that overall convenience store density increased with declines observed only in single years 2000 and 2007. [5] The average convenience store density in a state increased from 207 convenience stores per million people in 1997 to 230 in 2009.[5] These findings demonstrate that during a period of greater adoption of smoke free air policies and higher state cigarette excise taxes that convenience stores were not harmed by these tobacco control measures.

Conclusion

Several studies [1, 3, 5, 7] have assessed the economic impact of tobacco control efforts on retail outlets. These studies show that POS tobacco control measures do not pose negative long term effects to the overall retail economy.

-

Ribisl KM, Evans WN, Feighery EC. Falling cigarette consumption in the U.S. and the impact upon tobacco retailer employment. In: Bearman P, Neckerman K, Wright L, eds. Social and Economic Consequences of Tobacco Control Policy. New York:Columbia University Press, 2011.

More Resources:

- For more information check out this series from Campaign For Tobacco Free Kids on rebutting common, misleading claims from NATO/Swedish Match against POS policy:

- Public Health and Tobacco Policy Center’s “Oh, Snap! Countering Tobacco Industry Opposition to Local Tobacco Controls“

- Berkeley Media Studies Group’s What surrounds us shapes us: Making the environmental case for tobacco control

- Potential Effects on Tobacco Tax Revenues of a Ban on the Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products, Tobacconomics

- Potential Effects of a Ban on the Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products in California, Tobacconomics

- Flavored Tobacco Bans: Fact vs. Fiction, Public Health Law Center