Tobacco 21

“Tobacco 21” policies are a way to keep harmful, addictive products – like cigarettes, cigars, and electronic nicotine delivery systems – out of the reach of young people, whose developing brains are being wired with lifelong habits. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, over 80% of adults who still smoke got started before they turned 18, and nearly 95% started before age 21.[1] On December 20, 2019, the minimum legal sales age was raised from 18 to 21 nationwide. When the federal legislation went into effect, 19 states had already raised the minimum legal sales age to 21. While the federal legislation expanded Tobacco 21 to all 50 states, states and localities can pass or strengthen their own age of sale laws to ensure state and local agencies have the authority to enforce the higher age of sale, incorporate other best practices, and ensure retailers are following the law.

What’s on this page?

- Minimum Legal Sales Age Defined

- Best Practices for Implementation and Enforcement

- History of the T21 movement

- Evidence for raising the MLSA

- How to Get Started

What is the Minimum Legal Sale Age?

The minimum legal sale age (MLSA) prohibits retailers from selling tobacco products to anyone under that age. Prior to 2019, in most places across the country, that age was set at 18. Three states (Alaska, Alabama, and New Hampshire) had a minimum age of 19. However, historical news archives and tobacco industry documents reveal this was not always the case. In 1920, at least one third of states had a MLSA of 21, but those laws were eroded in part due to aggressive tobacco industry lobbying.[2] Now, after many years of state and local action to again raise the age to 21, a nationwide standard of 21 as the minimum legal sale age for all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, has been enacted.

Best Practices for Implementation and Enforcement

Effective and comprehensive Tobacco 21 policies on a state and local level start with strong language, ample planning for implementation and enforcement, and an equity focus. According to the “Tobacco 21: Model Policy” backed by a consortium of national public health groups, strong MLSA policies:

- Define tobacco products to include current and future tobacco products, including e-cigarettes

- Prohibit the sale of tobacco products to persons under the age of 21

- Require the tobacco retailer or their employee to verify the age of the purchaser prior to the sale

- Require tobacco retailers to post signs stating that sales to persons under the age of 21 are prohibited

- Designate an enforcement agency and establish a clear enforcement protocol

- Create a tobacco retail licensing program if the jurisdiction has the authority to do so under state law

- Dedicate funding to fully cover enforcement costs, either through licensing fees or as a provision in a state statute or local ordinance

- Provide authority for the state, county, or municipality to inspect tobacco retailers for compliance with MLSA 21 and a mandated minimum number of annual compliance checks for every tobacco retail establishment

- Provide penalties focused on the tobacco retailer or licensee rather than the youth purchaser or non-management employee. This would mean eliminating purchase, use, and possession (PUP) penalties where they exist in current tobacco sales laws or policies

- Establish a civil penalty structure for violations rather than a criminal penalty structure to avoid unintended consequences that disproportionately impact marginalized communities and undermine the public health benefits of the policy

- Where state legislation is pursued, ensure that local jurisdictions have the authority to enact more stringent regulations for tobacco products than state or federal law

- Learn about equitable enforcement practices here

Colorado passed an exemplary, comprehensive Tobacco 21 bill in July 2020. While the law primarily increased the MLSA to 21 to comply with federal regulations, the legislation also repealed any criminal penalty for minors who purchase or attempt to purchase tobacco products. It also required all tobacco retailers to become licensed in the state, prevented new tobacco retailers from establishing shops within 500 feet of schools, and prohibited retailers that sell electronic nicotine delivery systems from advertising these products on the exterior of their stores. Additionally, the language in the licensing provision updated and detailed statewide enforcement efforts, which now include a minimum of two compliance checks per year, and established penalties, like fines and license suspensions, for retailer violations.

In order for policies raising the minimum legal sale age for tobacco products to 21 to be impactful, they must be adequately enforced. Best practices include having an articulated plan for enforcement with responsibility given to a single agency, ongoing compliance checks with a minimum number of checks for each retailer per year, creating a tobacco retailer licensing program, providing dedicated funding for enforcement, having high penalties (e.g. high fines, license suspension or revocation) for violators, and practicing merchant education.[11] In addition, some researchers suggest that as repeat violators have their license to sell tobacco revoked, a cap and winnow policy could be implemented that prevents them from being reissued, reducing tobacco retailer density and further reducing access to tobacco.[11] For more information, review Raising the Tobacco Sale Age to 21: Building Strong Enforcement into the Law. Research shows that neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black, Latino, and young residents are more likely to have higher rates of underage sales.[12] Oversampling for inspection in these areas, for instance by using stratified, cluster sampling at the zip-code or census-tract level, may help ensure retailer compliance and reduce this disparity.[12,13]

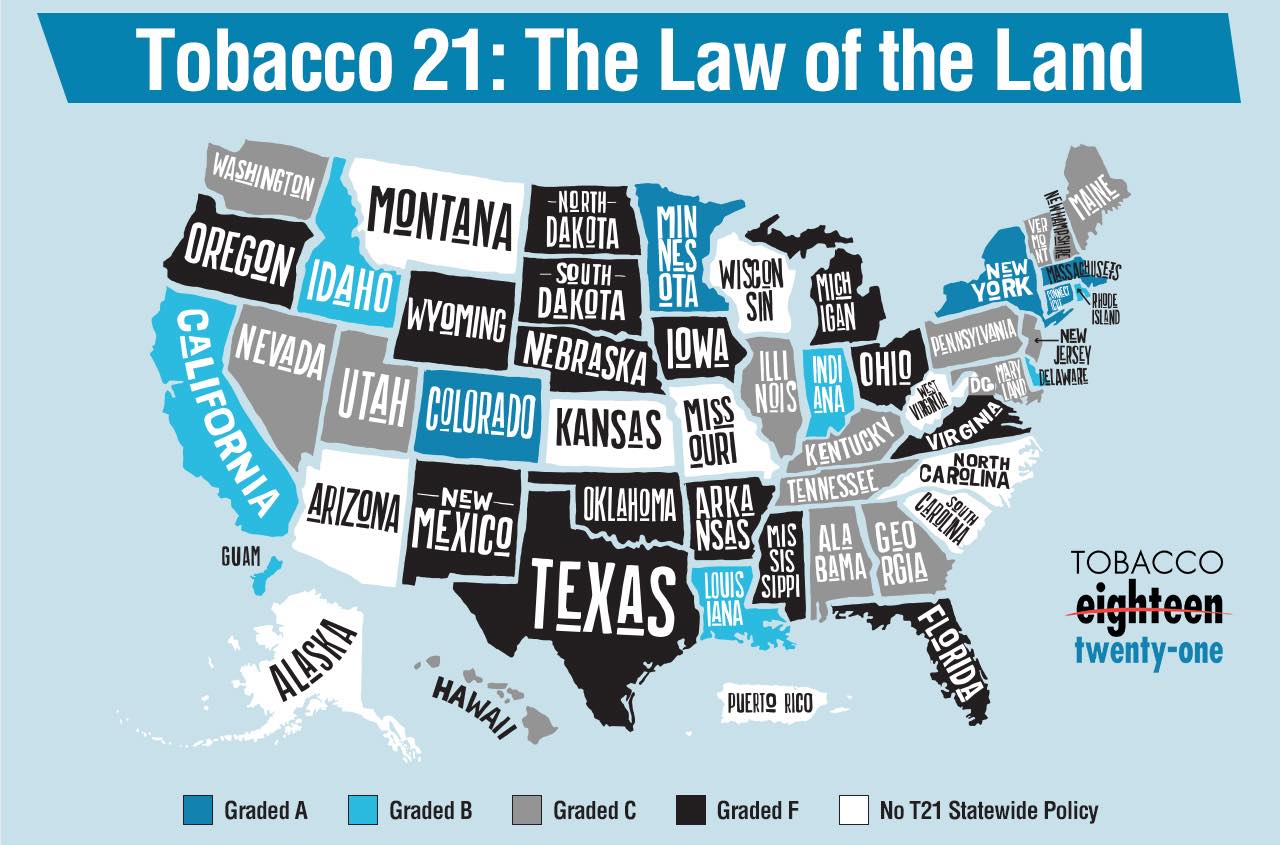

The Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation (Tobacco21.org), has created Tobacco 21 Grade Cards for each current statewide Tobacco 21 law to track how it matches up against best practices. Check them out to see how your state’s law stacks up or where it could be improved.

History of the Tobacco 21 Movement

As of August 2022, the total list of states and cities that have raised their MLSA to 21 includes more than 570 cities and counties in 45 different states.The map below from Tobacco21.org, which is current as of August 8, 2022, illustrates in white the remaining states in the US without a statewide T21 policy in place. A current map can be found here.

The movement began in 2005 when Needham, Massachusetts became the first town in the US to enact a law raising the MLSA to 21. In the four years following implementation of the law, youth smoking rates in Needham decreased by approximately half, from 13% to 6.7%; in surrounding communities, youth smoking rates only fell from 15% to 12.4%.[3,4] New York City then made news in October 2013 when they passed historic tobacco control legislation, which included raising the MLSA to 21. Many cities and counties nationwide later followed suit, with early adopters including Cleveland, OH, Chicago, IL, and many localities in the Greater Kansas City Area.

At the state level, Hawaii became the first state to pass legislation raising the MSLA to 21; Hawaii’s Tobacco 21 law was passed in June of 2015 and went into effect on January 1, 2016. In 2016, only one other state, California, raised its MSLA to 21, and in 2017, New Jersey followed suit, becoming the third state with Tobacco 21 legislation at the state level. In 2018, three other states – Oregon, Maine, and Massachusetts – enacted their own Tobacco 21 laws; at this point, 230 of Massachusetts’ towns and counties, including Boston, had also raised the MLSA to 21. Throughout 2019, a surge of other states passed similar legislation.

On December 20, 2019, federal legislation was signed into law raising the minimum legal sale age from 18 to 21 nationwide. The policy went into effect immediately and is enforced by the FDA underage decoys to conduct compliance checks. See the FDA’s Frequently Asked Questions about the law for additional information.

While the federal legislation expanded Tobacco 21 to all 50 states, any law must be adequately enforced to be effective. The new federal law provides an opportunity for states and localities to pass or strengthen their own age of sale laws to amplify enforcement efforts, implement licensing, heighten tobacco control measures, and ensure equity. Learn about equitable enforcement practices here. States and localities across the country continue to pass their own Tobacco 21 bills, extending enforcement authority to local and state agencies.

However, not all laws are written the same, and some states have passed Tobacco 21 legislation with significant drawbacks, such as those listed below:

- Preemption. Utah is one example of a state that, through its Tobacco 21 legislation, has preempted local legislation relating to the sale, placement, and display of tobacco and vaping products. This type of preemption can be problematic for local tobacco advocates who recognize that state and federal policy is often too broad to address the specific and unique needs of their community. Preemption impedes policy change at the local level that advances tobacco control efforts and drives state level change. Preemption has long been one of the tobacco industry’s favored tactics to block progress and can be difficult to overturn or reverse. Learn more about preemption here. As more states look to pass Tobacco 21 to comply with the federal legislation, tobacco control advocates should remain vigilant of Big Tobacco lobbying to include preemptive language in state MLSA legislation, as tobacco companies have a history of throwing their support behind laws that sound good on the surface, but in reality are weak, unenforceable and/or preemptive.

- Exemptions. States, including California, Arkansas, and Texas, previously exempted certain populations like military personnel and veterans from the raised MLSA; however, the federal legislation made such exemptions illegal on a federal level so provisions such as these being included at the state or local level will not be an issue moving forward.

- Purchase, Use, and Possession (PUP) laws, which penalize and criminalize underage youth for purchasing, using, and possessing tobacco products, are yet another set of provisions that reduce the strength and effectiveness of Tobacco 21 laws. As of April 2019, all but 7 states had some sort of PUP provision included in their legislation. These laws have shown little evidence in deterring youth smoking, especially among those at higher risk for smoking, and may actually have adverse consequences for youth already addicted. Additionally, these laws are notorious for being inequitably enforced, with youth of color being disproportionately affected. Data has also shown that PUP laws are four times more likely to be enforced than the laws that actually prohibit retailers from selling tobacco to underage minors. Placing the onus of responsibility on youth is neither evidence-backed nor best practice. Ultimately, the burden of responsibility should be placed on the retailer, rather than the underage purchaser, and PUP laws, as well as any associated criminal penalties, should be replaced with a civil penalty structure. Learn more about PUP laws in the following resources:

-

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’ Youth Purchase, Use, or Possession Laws are Not Effective Tobacco Prevention

- ChangeLab Solutions’ PUP in Smoke: Why Youth Tobacco Possession and Use Penalties are Ineffective and Inequitable

Some localities have also implemented policies that require clerks to be above the minimum legal sale age for tobacco in order to reduce sales to minors. In a test conducted in Massachusetts, in which underage people who smoke attempted to purchase cigarettes, researchers found that, when the underage purchasers were attempting to purchase tobacco products from underage clerks, their chances of purchasing successfully went up dramatically. However, policies such as this may limit jobs for teenagers and young adults, which is a concern in many rural areas.

Though Tobacco 21 is now mandated through federal legislation, the Tobacco 21 movement has consistently received broad public support. Multiple nationwide surveys have found that approximately 75% of nationally surveyed adults, including people who currently smoke and individuals aged 13-17 [5] and 18-21, who would be most impacted by the law, support Tobacco 21. [6,7] Public support is consistent across all regions of the US and is higher than support for raising the age to 19 or 20 years of age. [8] Some areas have found that Tobacco 21 policies can be developed and adopted in a shorter time frame and with fewer resources, can be targeted to a smaller group of stakeholders, and are perceived as less politically risky than other tobacco control measures such as smoke-free policies.[9]

The Evidence for Raising the Age to 21

In 2018, 4.9 million middle and high school students used some form of tobacco.[14] According to the 2012 Surgeon General’s report, youth initiation is a major factor in the tobacco epidemic.[15]

Modeling data:

- A model developed by researchers at UC Irvine showed that smoking prevalence for 15-17 year olds would drop from 22% to 9% in only seven years if the age of purchase were increased to 21 across the U.S.[16]

- Models from a report by the Institute of Medicine suggest that smoking prevalence overall will drop significantly between 2015 and 2100 due to previously instituted tobacco control policies even with the MLSA at the status quo. However, they project that smoking prevalence would drop by an additional 12% if the MLSA were raised to 21, compared to only an additional 3% if the MLSA were raised to 19.

Evaluation data:

- In Oregon, a short-term evaluation of the state’s Tobacco 21 law, which went into effect on January 1, 2018, showed that recent tobacco use initiation decreased from 34% the month before the law took effect to 25% nine months after the law took effect among current tobacco users ages 13-17 and from 23% to 18% during that time among current tobacco users ages 18-20. In addition, perceived ease of access to tobacco decreased among tobacco users ages 18-20.

- In California, an evaluation of the state’s Tobacco 21 law found that the retailer violation rate [RVR] using youth decoys under age 18 decreased from 10.3% before the law was in effect to 5.7% afterwards.[17] As well, in a study of over 1,500 young adults aged 18-20, 54% of cigarette purchasers and 44% of e-cigarette purchasers reported it felt more difficult to purchase these tobacco products after implementation of Tobacco 21.[23]

- An assessment of cigarette pack sales in California and Hawaii found that implementation of a Tobacco 21 policy was associated with a reduction in cigarette sales of 13.1% in California and 18.2% in Hawaii.[25]

- A study assessing New York City’s Tobacco 21 law found that, while the rate of adolescent tobacco use declined in New York City following the policy’s implementation in 2014, the rate of decline in adolescent tobacco use was greater in four Florida cities that did not have a Tobacco 21 policy in place.[20] While rates didn’t necessarily decrease as fast as in other cities, New York City also already had many strong tobacco control policies in place (e.g. high excise taxes, a minimum price law with a price promotion ban, strong smoke-free air laws, and a ban on flavored tobacco products), which may have had a greater effect on adolescent use rates than Tobacco 21.[19] In addition, New York City has a very diverse market with many small independent retailers and many neighboring areas without strong tobacco policies. Impacts of Tobacco 21 legislation may vary between localities, and researchers suggest that greater enforcement and monitoring is necessary to achieve the full benefits of a Tobacco 21 policy.

- A national study conducted from November 2016 to May 2017 through an online survey found that across the US, 18-20 year-olds who had tried a combustible cigarette or e-cigarette but lived in places with a Tobacco 21 law were 39% less likely to have recently smoked or to regularly smoke than 18-20 year-olds who lived in a place without a Tobacco 21 law.[21]

Tobacco use is costly to society.Every year, smoking costs the US over $289 billion in health care costs and lost productivity. If the MLSA were raised to 21, simulations project a net cumulative savings of $212 billion dollars through decreased projected prevalence of tobacco use and the subsequent savings in medical costs.[18]Population health gains in terms of both length of life and health-related quality of life are likely to be 7 times greater when youth smoking initiation is prevented, rather than cessation being encouraged among adults who smoke.[19] According to the 2012 Institute of Medicine report, raising the MLSA; to 21 could prevent 223,000 premature deaths, 50,000 deaths from lung cancer, and 4.2 million years of life lost.

A higher MLSA limits social channels through which youth can get enough cigarettes to develop a regular smoking habit. Youth frequently rely on getting cigarettes from the 18 to 20 year-olds in their social circles.[20] Raising the MLSA reduces access to legal buyers in their daily routine (especially at school) and limits successful store purchases.[15]

Recruiting young adults as “replacement smokers” has long been a tobacco industry strategy to sustain their business. People who start smoking at an early age are more likely to later smoke regularly and heavily.[19] But as one RJR Reynolds researcher said in 1982,

“If a man has never smoked by age 18, the odds are three-to-one he never will. By age 24, the odds are twenty-to-one.”

Motivated by this knowledge, the tobacco industry markets directly to 18 to 21 year-olds through promotions and marketing at bars, clubs, and parties in college towns as well as tobacco corporation-sponsored music and sporting events, capitalizing on this age group’s transition to adulthood as an opportunity to hook them on nicotine.[15, 22]

Reducing youth’s access to tobacco products is key for their health. Brain development is not complete until the 20s, and nicotine may chemically alter a teen’s developing brain, making them more susceptible to addiction. Analysis of data from the 2014-2015 Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey found that those who started smoking before the age of 18 were 2.15 times as likely to become nicotine dependent in their lives, compared to those who started smoking at age 21 or older; furthermore, those who started smoking between the ages of 18 and 20 were 1.25 times as likely to become nicotine dependent in their lives than those who started smoking at age 21 or older.[24] At this vulnerable age, teenagers may also incur more lasting damage from tobacco smoke.

How to Get Started

- Consult legal experts. The content on this site and associated resources are no substitute for actual legal advice.

- Assess readiness. Complete the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids’Campaigns to Raise the Minimum Legal Sale Age to 21: Readiness Assessment Questions

- Assess existing youth access laws. Check to see what your state or community’s existing law is regarding youth access to tobacco. There may be room for the current law to be improved.

- Is it a sale age policy or a PUP policy?

- Is there preemption?

- What penalties are included, and for whom?

- Are all products (including e-cigarettes) covered?

- What is the current enforcement infrastructure?

- Consider health equity impacts. For an example of a Health Equity Impact Assessment for Tobacco 21, see Multnomah County, Oregon’s example. Download the executive summary or the full report

- Determine if your locality or state has a tobacco retailer licensing program. Tobacco 21 can be included as part of a retailer licensing program, which would also provide a list of retailers to use for enforcement and an enforcement structure.

- Plan for enforcement and implementation up front. Determine who will be responsible for compliance, enforcement, and evaluation, and ensure that there is a dedicated budget for enforcement efforts.

- Consider increasing excise taxes to adjust for lost revenue over time and to see more immediate effects in reducing initiation. Learn more and see an example of one way to do this in Tobacco 21 in Michigan: New Evidence and Policy Considerations

- Review model policies and best practices

- Tobacco 21 Model Policy

- Tips & Tools: Tobacco 21

- If your local government is preempted, consider a voluntary resolution, using the Public Health Law Center’s Sample Resolution: Tobacco 21

- Conduct public opinion surveys to measure community support for raising the minimum legal sales age to 21.

- Engage stakeholders. Review the CDC’s Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs for tips.

More Resources:

-

- Tobacco21.org provides updates on the Tobacco 21 movement and access to specific policy information at the state level.

- CDC’s

- Federal Tobacco 21: Considerations for Tribal Communities from the American Indian Cancer Foundation, the Public Health Law Center, the Minnesota Department of Health

- Counter Tobacco Podcast: Learn more about the Tobacco 21 movement and best practices in this podcast episode on the topic, and learn specifically about the federal Tobacco 21 legislation, passed in December of 2019, in this episode.

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids’:

- Stories from the Field – learn how other communities passed their Tobacco 21 policies:

- ASTHO’s Tobacco 21 Legislative Policy Analysis

- Ohio State University’s College of Public Health’s Running the Numbers: Raising the Minimum Tobacco Sales Age to 21

- Law and the Public Health’s Raising the Tobacco Sales Age to 21: Surveying the Legal Landscape